OCR Specification focus:

‘Explain how K controls equilibrium position when concentration, pressure or temperature change; apply principles to others.’

This topic explains how equilibrium position responds to changing conditions and how the equilibrium constant governs extent of reaction in reversible chemical systems.

Understanding Equilibrium Position

The equilibrium position describes the relative amounts of reactants and products present once a reversible reaction has reached equilibrium. It does not indicate speed, but rather how far a reaction proceeds before opposing rates become equal.

At equilibrium, the forward and reverse reactions occur at equal rates, meaning concentrations remain constant, not necessarily equal. The position is strongly linked to the numerical value of the equilibrium constant, K.

The Role of the Equilibrium Constant (K)

For a given reaction at a fixed temperature, the equilibrium constant has a constant value. It provides a quantitative measure of how product-favoured or reactant-favoured an equilibrium is.

Equilibrium constant (K): A numerical value showing the ratio of product concentrations to reactant concentrations at equilibrium, each raised to their stoichiometric powers, at a fixed temperature.

A large value of K indicates an equilibrium position lying far to the right, with products favoured. A small K indicates reactants are favoured. Importantly, K controls the equilibrium position, not the speed of reaction.

Even when conditions such as concentration or pressure are altered, the value of K remains unchanged provided the temperature stays constant.

Changes in Concentration

Altering the concentration of a reactant or product disrupts equilibrium. The system responds by shifting position to oppose the change and restore equilibrium.

When concentration changes:

Increasing reactant concentration shifts equilibrium towards products.

Increasing product concentration shifts equilibrium towards reactants.

Decreasing concentration has the opposite effect in each case.

Although concentrations at equilibrium change, the value of K does not. Instead, the reaction quotient temporarily differs from K, driving the system to re-establish equilibrium.

This behaviour demonstrates that K determines the final equilibrium position, regardless of how the system is disturbed by concentration changes.

Changes in Pressure (Gaseous Equilibria)

Pressure changes only affect equilibria involving gases where the total number of moles of gas differs between reactants and products.

The effect of increasing pressure:

Equilibrium shifts towards the side with fewer moles of gas.

This reduces pressure by decreasing total gas particles.

The effect of decreasing pressure:

Equilibrium shifts towards the side with more moles of gas.

If the number of gaseous moles is equal on both sides, pressure changes have no effect on equilibrium position. As with concentration changes, K remains constant at constant temperature.

For gaseous equilibria, increasing pressure (decreasing volume) shifts equilibrium towards the side with fewer moles of gas.

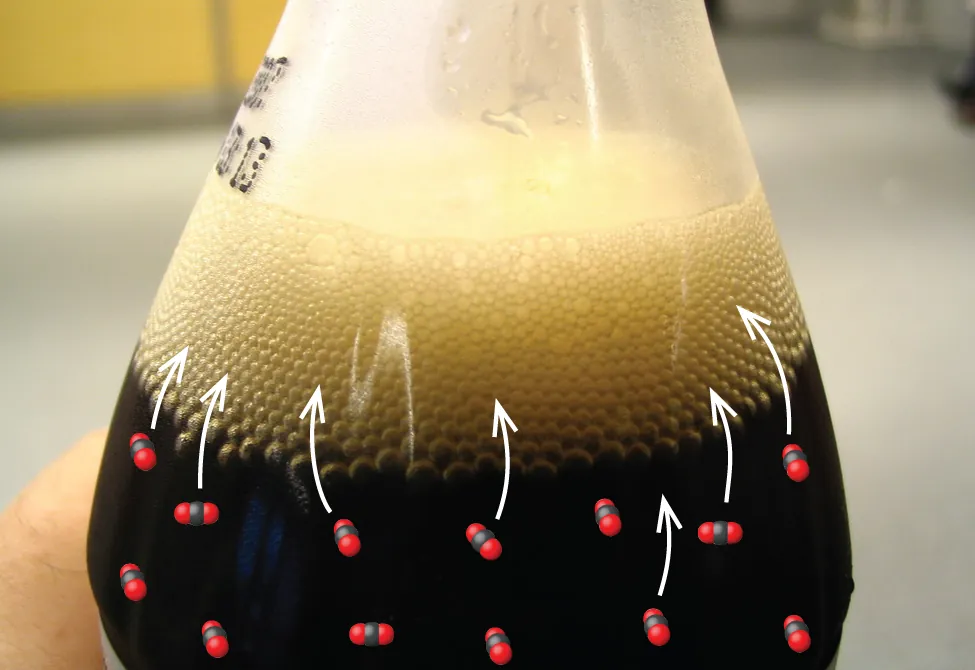

Opening a carbonated drink lowers the pressure above the liquid, so the dissolved–gas equilibrium shifts to produce more CO₂(g), forming bubbles. This illustrates how decreasing pressure favours the side with more gas particles. Extra detail: the solubility framework goes beyond the core syllabus focus. Source

Changes in Temperature

Temperature is unique because it does affect the value of K. Changing temperature alters the relative rates of forward and reverse reactions differently.

The effect depends on the reaction enthalpy:

For exothermic reactions, increasing temperature decreases K and favours reactants.

For endothermic reactions, increasing temperature increases K and favours products.

Exothermic reaction: A reaction that releases heat energy to the surroundings.

Endothermic reaction: A reaction that absorbs heat energy from the surroundings.

This change occurs because heat can be treated as a reactant or product. Temperature changes therefore alter equilibrium position by changing K itself, not merely shifting concentrations.

Changing temperature is the only common stress that changes K, so it can move the equilibrium position even when concentrations are allowed to re-equilibrate.

The colour of the NO₂/N₂O₄ equilibrium mixture deepens as temperature increases, showing a shift in equilibrium position. This visually demonstrates that temperature changes alter K. The specific system is illustrative, but the principle applies to all equilibria. Source

Catalysts and Equilibrium Position

A catalyst increases the rate at which equilibrium is reached but does not change the equilibrium position.

Key points about catalysts:

They lower activation energy for both forward and reverse reactions.

They increase reaction rates equally in both directions.

They do not affect the value of K.

As a result, catalysts allow equilibrium to be established faster without changing the proportions of reactants and products present at equilibrium.

Applying the Principles to Other Systems

The principles governing equilibrium position are universal and apply to all chemical equilibria, including industrial processes and acid–base systems.

When analysing any equilibrium:

Identify how a change affects the system.

Determine whether K remains constant or changes.

Predict the direction of shift based on opposing the disturbance.

Relate the final position back to the magnitude of K.

These ideas underpin the optimisation of equilibrium-controlled reactions, such as maximising yield in reversible industrial processes, where conditions are carefully chosen to favour the desired products while respecting the constraints imposed by the equilibrium constant.

Understanding that K controls equilibrium position, while conditions like concentration and pressure only cause temporary shifts, is central to mastering chemical equilibrium at A-Level Chemistry.

FAQ

If a change does not affect the variables in the equilibrium expression, no shift will occur.

Examples include:

Pressure changes when the number of moles of gas is equal on both sides

Adding a solid or pure liquid to a heterogeneous equilibrium

In these cases, the equilibrium position remains unchanged because the disturbance does not alter the ratio defined by K.

The reaction quotient, Q, uses the same expression as K but applies to current, non-equilibrium concentrations.

If Q < K, the reaction shifts towards products

If Q > K, the reaction shifts towards reactants

This comparison explains the direction of shift after a disturbance and reinforces that equilibrium position is governed by K at constant temperature.

Equilibrium position describes relative amounts of reactants and products in general terms.

K provides:

A numerical measure of how far a reaction proceeds

A temperature-dependent constant for comparison between systems

This distinction allows chemists to discuss shifts qualitatively while using K for precise control and prediction.

Continuous removal of a product prevents equilibrium from fully establishing.

As products are removed:

The system repeatedly shifts to replace them

The reaction can be driven towards near-complete conversion

This principle is used industrially to maximise yield without changing K.

For gaseous equilibria, pressure and volume are inversely related at constant temperature.

Decreasing volume increases pressure

Increasing volume decreases pressure

Both changes alter collision frequency and favour the side with fewer or more moles of gas respectively, shifting the equilibrium position without changing K.

Practice Questions

A reversible reaction reaches equilibrium at a constant temperature.

Explain why changing the concentration of a reactant changes the equilibrium position but does not change the value of the equilibrium constant, K.

(2 marks)

States that changing concentration disturbs equilibrium and causes a shift to oppose the change. (1 mark)

States that K remains constant because temperature is unchanged / K only depends on temperature. (1 mark)

The reversible reaction below is carried out in a sealed container:

A(g) + 2B(g) ⇌ C(g) + D(g) ΔH = −ve

The system is initially at equilibrium at a fixed temperature.

(a) Predict and explain the effect on the equilibrium position when the pressure is increased.

(b) Predict and explain the effect on the equilibrium position and the value of K when the temperature is increased.

(c) Explain the effect, if any, of adding a catalyst to this system.

(5 marks)

(a) Pressure increase (2 marks)

Correct prediction: equilibrium shifts to the right. (1 mark)

Explanation: shift is towards the side with fewer moles of gas (2 moles on the right vs 3 on the left). (1 mark)

(b) Temperature increase (2 marks)

Correct prediction: equilibrium shifts to the left / towards reactants. (1 mark)

Explanation: reaction is exothermic so increasing temperature favours the endothermic (reverse) reaction and decreases K. (1 mark)

(c) Catalyst (1 mark)

States that a catalyst does not change the equilibrium position or the value of K, only increases the rate at which equilibrium is reached. (1 mark)