AP Syllabus focus:

‘Native peoples migrated across North America and formed distinct, complex societies by adapting to and transforming diverse environments.’

Indigenous societies in 1491 were remarkably diverse, shaped by environmental variation, cultural innovation, and long histories of adaptation that produced distinct regional economies, settlement patterns, and social structures.

North America Before European Contact

Before Europeans arrived, the continent was home to millions of Indigenous peoples whose societies had developed over thousands of years. These communities were not isolated; they interacted through networks of trade, diplomacy, warfare, and cultural exchange. Their diversity was rooted in the ways Native peoples adapted to and transformed their environments, creating complex cultures suited to local ecological conditions.

Environmental Diversity and Indigenous Adaptation

Environmental differences across North America profoundly influenced how Native communities lived, organized their societies, and interacted with neighboring groups.

Major Environmental Regions

Arid Southwest: Characterized by deserts, mesa systems, and limited rainfall.

Great Basin: A region of dry basins and rugged mountains.

Great Plains: Grasslands dependent on bison herds.

Eastern Woodlands: Forested areas rich in game, waterways, and fertile soil.

Pacific Northwest and California: Coastal and forest ecosystems abundant in marine and plant resources.

Because of these varied landscapes, Indigenous peoples crafted distinct strategies for survival and development.

This map shows major Indigenous cultural areas in North America at the time of early European contact. Each region reflects a broad pattern of environment, subsistence, and social organization. The map includes additional regional labels and boundaries that extend beyond the specific examples discussed in these notes but support the central idea of environment-shaped cultural diversity. Source.

Cultural and Social Diversity Among Indigenous Peoples

Complex Political Structures

Many Indigenous societies created sophisticated political systems ranging from autonomous bands to chiefdoms and confederacies.

Some Eastern Woodlands communities, such as the Iroquois-speaking nations, formed advanced alliances like the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, known for shared governance and diplomacy.

In the Mississippi River Valley, large chiefdoms such as Cahokia developed hierarchical leadership and centralized ceremonial centers.

Varied Social Organization

Social structures depended on subsistence strategies and cultural traditions.

Some societies were kinship-based, emphasizing extended family ties.

Others built stratified systems with formal leadership roles tied to religious or political authority.

Gender roles were diverse; many groups practiced complementary gender systems, in which men and women exercised different but equally valued responsibilities.

Regional Economic Patterns

Indigenous subsistence strategies reflected adaptation to local environments and included:

Agriculture, especially in fertile regions where maize, beans, and squash could be grown successfully.

Hunting and gathering, particularly in areas where game and wild plants were plentiful.

Fishing and maritime economies, especially along the Pacific Coast with its rich salmon and shellfish populations.

The spread of maize agriculture, a crop domesticated in Mesoamerica, was especially transformative, enabling greater population density and more settled lifestyles in many regions.

Transforming the Environment

Indigenous peoples did not simply adapt to their environments—they reshaped them.

Methods of Environmental Modification

Controlled burns to promote new plant growth and improve hunting conditions.

Irrigation systems in the Southwest to support maize production in arid climates.

Terracing and field systems used by some agricultural communities to maximize crop yields.

Selective harvesting and resource management to maintain long-term ecological balance.

Long-Term Impacts

These practices demonstrate that Indigenous societies exerted intentional, sustainable control over landscapes, contradicting later European assumptions that the continent existed in a “natural” or “untouched” state.

Regional Examples of Indigenous Diversity

Southwest: Agricultural and Irrigation Societies

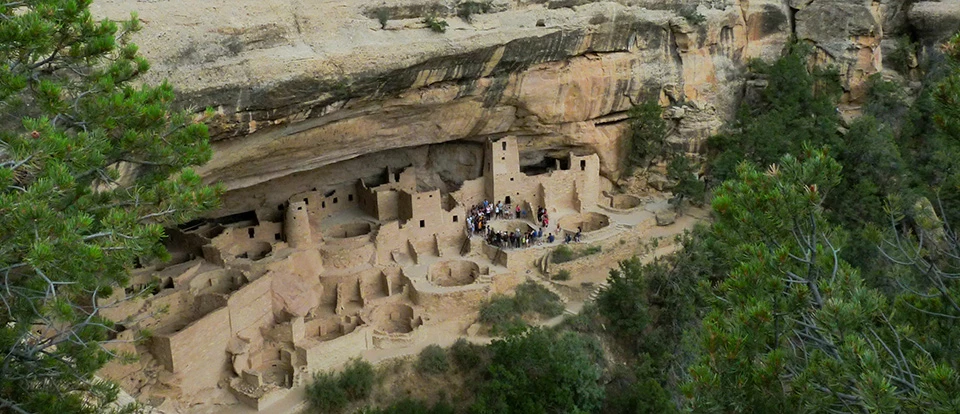

People such as the Puebloans (Ancestral Pueblo, Hopi, Zuni) constructed multi-story adobe dwellings and developed advanced irrigation networks.

This photograph shows Cliff Palace, a large Ancestral Puebloan cliff dwelling with multi-story masonry rooms and circular kivas built within a sandstone alcove. It reflects how maize agriculture and careful water use supported dense, permanent settlements in the arid Southwest. The image also includes modern visitors and preservation features that extend beyond the AP syllabus but help convey the scale of the site. Source.

Irrigation: A system for supplying land with water through channels, canals, or other technologies to support agriculture in dry environments.

In addition to farming, Southwestern groups produced ceramics, textiles, and ritual objects central to their cultural life.

Great Basin and Great Plains: Mobility and Resource Flexibility

In regions with sparse or unpredictable resources, communities relied on mobility. This adaptability enabled survival in environments where permanent agriculture was difficult.

Great Basin groups such as the Shoshone and Paiute traveled seasonally to gather seeds, nuts, and small game.

Plains communities before the arrival of the horse hunted bison on foot, using cooperative strategies and communal labor.

These societies maintained rich cultural traditions, including storytelling, spiritual practices, and trade with neighboring peoples.

Eastern Woodlands: Mixed Economies and Settled Villages

In the Northeast and along the Mississippi River, fertile soils and abundant forests supported mixed economies combining agriculture, hunting, and fishing.

Many groups developed permanent or semi-permanent villages, often constructed around communal longhouses or mound complexes.

Social and political structures varied widely, from small family units to extensive chiefdoms with regional influence.

Pacific Northwest and California: Coastal Abundance

Access to coastal waters and dense forests produced some of the most complex hunter-gatherer societies in North America.

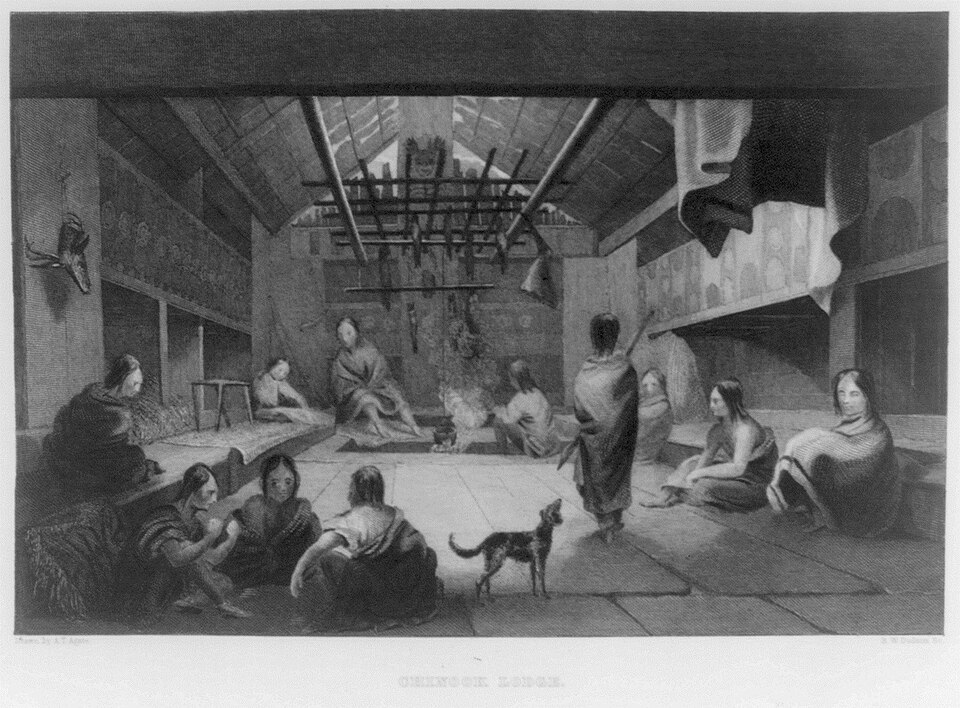

Peoples such as the Chinook and Chumash used ocean resources like salmon, whales, and shellfish to sustain large, sedentary communities.

This illustration shows the interior of a Chinookan plankhouse, with a central fire pit, raised wooden platforms for storage and sleeping, and communal living space for extended families. It highlights how Pacific Northwest peoples built substantial, permanent dwellings that matched their reliance on rich coastal and riverine resources. The image includes architectural and household details that extend beyond the AP syllabus but help visualize the complexity of these communities. Source.

Elaborate artistic and ritual traditions, including totem carving and potlatch ceremonies, reflected the wealth generated from coastal trade networks.

Interconnectedness Among Indigenous Peoples

Although diverse, Indigenous communities were linked through systems of exchange, diplomacy, and cultural borrowing.

Trade networks carried shells, minerals, crops, and cultural ideas across long distances.

Shared religious traditions, such as reverence for the natural world, appeared in many societies though expressed differently in each region.

Intertribal alliances and conflicts shaped political relationships long before Europeans arrived.

These connections show that Native America in 1491 was dynamic, interconnected, and highly organized.

FAQ

Trade networks linked distant regions, allowing ideas, technologies, and ceremonial goods to circulate long before European arrival.

Items such as shells, obsidian, copper, and specialised textiles moved across hundreds of miles, shaping prestige, diplomacy, and artistic styles.

These exchanges also facilitated intergroup alliances, reinforcing political relationships and helping maintain peace or manage conflict.

Many Indigenous groups viewed the natural world as animated by spiritual forces, which encouraged practices that balanced resource use with ecological stewardship.

Beliefs in sacred landscapes meant that hunting, farming, and gathering often followed ritual cycles to honour animal and plant spirits.

This worldview helped regulate resource exploitation, providing an informal but effective system of environmental management.

Population density correlated strongly with resource reliability.

Regions with dependable food sources—such as the salmon rivers of the Pacific Northwest or maize fields of the Southwest—could sustain permanent villages and large populations.

Areas with unpredictable resources, such as the Great Basin, remained lightly populated because mobility was necessary to secure food throughout the year.

Technologies developed in response to environmental needs rather than uniform cultural patterns.

Examples include:

• irrigation canals in the Southwest for maize farming

• birchbark canoes in the Eastern Woodlands for river travel

• plank-built ocean-going canoes in the Pacific Northwest

• hide-processing and efficient hunting tools in the Plains

These technologies reveal how societies engineered solutions tailored to their landscapes.

Gender roles were often shaped by the demands of the local environment.

In farming regions, women commonly took major responsibility for crop cultivation, granting them significant influence in community decision-making.

In mobile hunting groups, labour was more fluid, with both men and women contributing to food gathering, camp movement, and craft production.

Across many regions, gender roles operated through complementarity rather than strict hierarchy, allowing societies to distribute labour effectively.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks):

Identify one way in which Indigenous peoples in 1491 adapted to their local environment, and briefly explain how this adaptation shaped their society.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid environmental adaptation (e.g., irrigation in the Southwest, seasonal mobility in the Great Basin, mixed agriculture in the Eastern Woodlands, reliance on coastal resources in the Pacific Northwest).

1 mark for explaining how the adaptation shaped social, economic, or political life (e.g., irrigation enabling permanent settlements; mobility leading to smaller, flexible social groups).

1 mark for further detail or an additional linked consequence demonstrating clear understanding.

Question 2 (4–6 marks):

Explain how environmental diversity contributed to the development of distinct Indigenous cultures across North America in 1491. In your answer, refer to at least two different regions.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for a clear opening statement linking environmental diversity to cultural diversity.

1–2 marks for an accurate explanation of how one region’s environment shaped its society (e.g., Southwest irrigation agriculture producing settled villages).

1–2 marks for an accurate explanation of a second region (e.g., Great Basin scarcity leading to mobile lifeways; Pacific Northwest abundance supporting complex hunter-gatherer societies).

1 mark for demonstrating wider insight, such as trade connections, social organisation, or evidence of complexity tied to environmental adaptation.

Up to 6 marks total for coherent, well-developed explanation across regions.