AP Syllabus focus:

‘In early interactions, Europeans and Native Americans held different worldviews about religion, gender roles, family, land use, and power.’

Early encounters between Europeans and Native Americans exposed profoundly different beliefs about spiritual authority, family organization, gender roles, landholding, and political power, shaping cooperation, conflict, and long-term cultural transformation.

Divergent Worldviews in Early Encounters

The first century of contact between Europeans and Native Americans revealed contrasting assumptions about how societies should function. These differences shaped diplomacy, trade, conflict, and misunderstandings. Although cultural traditions varied widely among Indigenous nations, certain shared tendencies contrasted sharply with European expectations.

Map of major Native American cultural regions illustrating the environmental diversity that shaped distinct societies. It provides more regional detail than required but reinforces the concept of varied Indigenous worldviews prior to European contact. Source.

Religion and Spiritual Authority

Religion was one of the most visible divides. European explorers, missionaries, and settlers generally came from Christian societies that emphasized exclusive belief, hierarchical clergy, and scriptural authority. Native American religions, while highly diverse, broadly valued spiritual interconnectedness, sacred natural landscapes, and communal ritual practices.

Native American Spiritual Perspectives

Many Native communities viewed the world as filled with spiritual forces expressed through animals, celestial bodies, plants, and ancestors.

Animism: The belief that natural entities such as animals, rivers, and trees possess spiritual essence and agency.

Because of this worldview, ceremonies often aimed to maintain balance among human and nonhuman beings rather than obey a centralized religious institution.

These religious differences affected early diplomacy. Europeans often interpreted Indigenous rituals as “superstition,” while Native communities struggled to understand the exclusivity and conversion-driven nature of Christianity.

European Christian Perspectives

European leaders expected Native peoples to convert as part of establishing political authority. Missionaries—especially Spanish Catholic friars—believed they were obligated to replace Native belief systems. Europeans also viewed sacred spaces differently; churches were built on fixed sites, whereas many Indigenous traditions considered entire landscapes spiritually significant.

Gender Roles and the Organization of Labor

Gender norms strongly influenced how each group assessed the other’s society. Europeans came from patriarchal systems that privileged male authority in politics, property, and the family. In contrast, many Indigenous societies practiced gender complementarity, assigning men and women different but equally valued roles.

Indigenous Gender Systems

In numerous Native societies, women cultivated fields, controlled agricultural produce, and played key roles in family and community decision-making. Men often hunted, made tools, and engaged in diplomacy or warfare.

Matrilineal Descent: A kinship system in which lineage, inheritance, and social identity follow the mother’s line.

This led to female influence in clan leadership among groups like the Iroquois and Cherokee. Europeans often misinterpreted women’s agricultural labor as evidence of “backwardness,” failing to recognize women’s political and economic power.

European Gender Systems

European norms emphasized male dominance in landholding, government, and religious leadership. Women’s legal status was largely limited, especially under the English doctrine of coverture. These assumptions shaped early treaties and negotiations, as European emissaries dismissed or bypassed female leaders who held legitimate authority in Native nations.

Family Structure and Social Organization

Family systems also diverged. Europeans adhered mostly to nuclear families headed by male household leaders. Native societies often featured extended kin networks, flexible household structures, and clan-based identities.

Key Contrasts

Native kinship networks could include multiple households cooperating in resource use and childcare.

Clan membership shaped obligations, marriage rules, and political alliances.

Europeans, in contrast, expected households to be property-centered economic units.

These opposing systems affected settlement patterns and diplomatic expectations.

Land Use and Property

Conflicts over land use emerged quickly because Europeans and Native Americans conceptualized land in fundamentally different ways.

Indigenous Views of Land

Most Native societies treated land as communal, meaning individuals could use particular areas for hunting, farming, or seasonal migration but did not “own” land as private property. Land held spiritual significance and relationships to territory were rooted in use and kinship rather than written titles.

European Views of Land

European states promoted private ownership, with legal documents establishing boundaries and transferable property rights.

Private Property: A system in which individuals possess legal rights to own, control, and transfer land or goods.

Because Europeans equated land improvement—such as fences and permanent farms—with rightful ownership, they frequently argued that Native peoples had not made “proper” use of the land and thus had weaker claims. This justified territorial expansion in European eyes.

After these early misunderstandings, tensions over territory intensified as European settlements expanded and demanded permanent land cessions.

Power, Political Authority, and Diplomacy

Political expectations further shaped early interactions. Europeans saw governments as hierarchical institutions led by kings, nobles, or councils with authority to command subjects. Indigenous governance was often consensus-based, emphasizing community discussion and persuasion rather than coercive force.

Contrasting Political Assumptions

Native diplomacy relied heavily on kinship metaphors, ceremonial gift exchange, and community-wide agreement.

The Hiawatha Wampum Belt symbolizes the political union of the Haudenosaunee nations and expresses principles of shared authority and diplomacy that shaped early Indigenous–European interactions. Source.

Europeans, used to centralized states, sought singular leaders who could sign binding treaties.

These contrasts produced frequent diplomatic confusion.

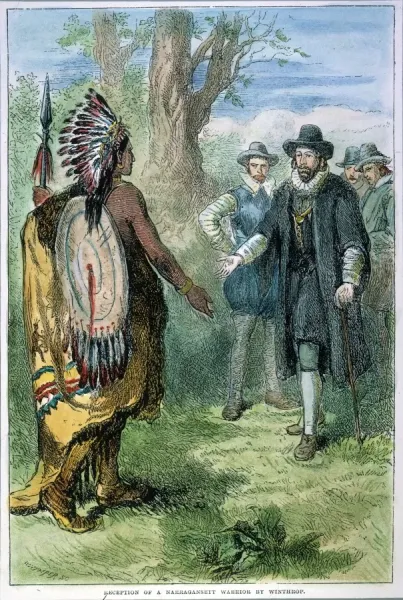

Engraving of Governor John Winthrop meeting a Narragansett warrior, illustrating contrasting European hierarchical authority and Indigenous diplomatic representation that often led to political misunderstanding. Source.

Impact on Early Encounters

Divergent beliefs about religion, gender, family, land, and power shaped every aspect of early contact. These differences contributed to:

misinterpretation of rituals and political decisions

disputes over women’s authority and kin obligations

conflicting expectations about land rights

contrasting diplomatic practices

tension surrounding conversion and spiritual authority

FAQ

Language barriers meant that even simple exchanges could be misinterpreted. Early communication relied on gestures, interpreters of varying skill, or ad hoc pidgin languages.

These limitations often caused:

Misread intentions in diplomacy

Incorrect assumptions about political authority

Disputes over trade agreements

Confusion over spiritual or ceremonial practices

As a result, misunderstandings were common even when both groups acted in good faith.

European observers expected societies to mirror patriarchal structures in which men controlled land, labour, and political institutions. When they saw Native women farming, holding influence in clan councils, or managing property, they assumed men were failing in their duties.

This led Europeans to:

Underestimate the political significance of female leaders

Misjudge the social cohesion of Native communities

Misinterpret economic roles as evidence of “savagery” rather than cultural difference

These assumptions influenced how Europeans negotiated treaties and alliances.

Native warfare often emphasised ritual, limited objectives, and symbolic actions. European warfare was typically aimed at decisive victory and territorial gain.

Key contrasts included:

Indigenous focus on restoring balance or avenging specific grievances

European use of overwhelming force or sustained military campaigns

Differing views on taking captives versus killing enemies

These differences sometimes escalated conflicts because each side misunderstood the other’s intentions and rules of engagement.

Europeans believed treaties were binding legal documents defining fixed boundaries and rights. Indigenous nations saw agreements as ongoing relationships rooted in reciprocity and ceremonial exchange.

This mismatch produced issues such as:

Europeans assuming permanent land cessions

Native diplomats expecting repeated gift-giving or reaffirmation of terms

Disputes over whether agreements applied to whole nations or specific communities

Such disagreements were common even when both sides believed they were honouring their obligations.

Many Indigenous nations made decisions through consensus among clan leaders, elders, and community representatives. Europeans, accustomed to hierarchical authority, expected a single ruler who could speak for an entire nation.

This caused problems in interactions, including:

Europeans treating local leaders as if they had absolute authority

Misinterpretation of hesitation or debate as resistance

Difficulty enforcing treaties that Indigenous diplomats understood as flexible

These political differences made early diplomacy unpredictable and often frustrating for both sides.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one significant difference between European and Native American worldviews during early encounters in the sixteenth century.

Question 1

1 mark: Identifies a valid difference (e.g., differing religious beliefs, land ownership concepts, or gender roles).

2 marks: Provides a clear explanation of the identified difference.

3 marks: Provides explanation with relevant historical detail or an accurate example drawn from early encounters.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which contrasting concepts of land use shaped early interactions between Europeans and Native Americans from 1491 to 1607.

Question 2

1–2 marks: Identifies at least one way contrasting land-use concepts shaped interactions.

3–4 marks: Explains how differing views on land (e.g., communal vs private ownership) contributed to cooperation, misunderstanding, or conflict.

5–6 marks: Develops a sustained argument assessing the extent of the impact, supported by historically accurate evidence (e.g., disputes over settlement, treaties, or territorial claims).