AP Syllabus focus:

‘Early interaction and trade were shaped by mutual misunderstandings as each group tried to make sense of the other.’

Early encounters between Europeans and Native Americans were shaped by unfamiliar cultural practices, contrasting worldviews, and language barriers, leading to persistent misunderstandings that influenced diplomacy, trade, and conflict across early contact zones.

First Encounters: Misunderstanding and Interpretation

Early Points of Contact and Cultural Gaps

When Europeans first reached the Americas in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, they entered regions populated by diverse Native American societies with well-established political, economic, and spiritual systems. Europeans often assumed their own practices were universal, while Native peoples interpreted Europeans through Indigenous frameworks. These differences produced significant mutual misunderstandings, shaping the earliest patterns of exchange and negotiation.

Worldviews and Communication Barriers

One of the most immediate obstacles was the lack of a shared language. Explorers, traders, and Indigenous communities relied on gestures, observation, and improvised vocabularies, which increased the likelihood of misinterpretation. Europeans often misread Indigenous diplomatic protocols—such as gift giving or ceremonial rituals—as signs of submission, while Native Americans frequently viewed European rigidness, private property norms, or formal treaties as culturally alien.

Worldview: A system of beliefs, values, and assumptions through which a group interprets the world and its place in it.

These divergent perspectives shaped how each group understood the intentions, status, and obligations of the other once contact began.

After these initial cultural encounters, misunderstandings grew as each side attempted to place unfamiliar behaviors into preexisting mental categories. Europeans frequently labeled Indigenous practices as “primitive” because they did not mirror European norms, while Native Americans sometimes viewed Europeans as spiritually powerful or dangerous due to their technologies and appearance.

Diplomatic Misinterpretations

Early diplomacy revealed deep contrasts in political organization and concepts of authority.

European assumptions of centralized leadership often conflicted with the decentralized or consensus-based leadership structures found in many Indigenous societies.

Negotiations with one local leader did not guarantee broader compliance, frustrating Europeans who expected hierarchical command structures.

Native leaders sometimes understood treaties as agreements based on ongoing reciprocity, not fixed permanent arrangements, leading to disputes when Europeans considered them binding contracts.

Reciprocity: A system of mutual exchange in which gifts, support, or obligations are returned over time to maintain social and political relationships.

European diplomatic expectations—rooted in written contracts and sovereign authority—did not align with Indigenous practices, contributing to conflict and confusion during early negotiations.

Miscommunication over sovereignty—who had ultimate authority over land and people—lay at the heart of many later conflicts.

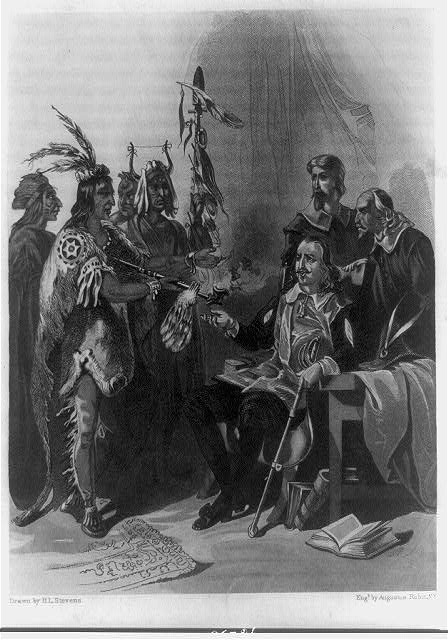

Engraving of Governor John Carver meeting Massasoit and Wampanoag leaders to negotiate peace and alliance in early New England. The scene highlights ceremonial postures and culturally distinct diplomatic gestures, which each side interpreted through its own traditions. Although slightly later than 1607, it illustrates the treaty councils and misunderstandings described in this subtopic. Source.

Trade, Exchange, and Economic Misunderstanding

Trade was one of the earliest forms of interaction, but even these exchanges were shaped by unfamiliar expectations. Native Americans often saw trade as a way to establish social bonds or alliances, whereas Europeans tended to interpret trade in strictly economic terms.

Key elements of misunderstanding included:

Value systems: Indigenous communities valued European goods based on usefulness and spiritual resonance, not scarcity or labor cost.

Gift giving: Europeans sometimes misread diplomatic gift exchange as theft, bribery, or tribute.

Resource concepts: Europeans expected fixed, exclusive rights to land or resources after trade agreements; Indigenous groups often understood agreements as granting shared access.

Europeans interpreted these exchanges through a commercial or market-based lens, expecting fixed prices, written contracts, and permanent ownership.

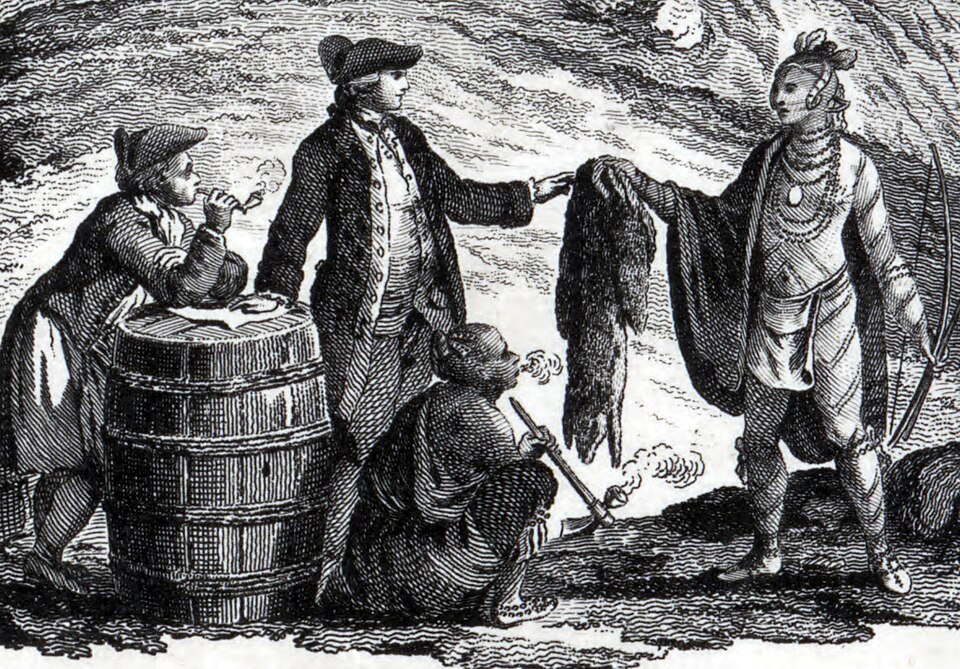

Engraving of Native Americans and European fur traders bartering furs for manufactured goods. The layout emphasizes the exchange of goods, the negotiation process, and unequal commercial expectations embedded in early contact. Although dated to 1777, it visually represents the types of cross-cultural trade and misunderstandings discussed in this subtopic. Source.

These different frameworks meant that the same transaction could signal friendship to one side and ownership to the other.

Religion and Spiritual Interpretation

Religious encounters were especially prone to misinterpretation, given fundamentally different spiritual worldviews.

Europeans believed in exclusive monotheism, missionary obligation, and institutionalized worship.

Many Indigenous groups practiced animism, ritual renewal, and community-centered spiritual leadership.

Animism: The belief that natural features, animals, and elements of the environment possess spiritual power or agency.

Missionaries frequently viewed Indigenous spiritual practices as evidence of ignorance, while Native peoples sometimes incorporated Christian rituals selectively, interpreting them within existing religious frameworks. Europeans misunderstood this syncretism as conversion, causing friction when Indigenous groups did not abandon older practices.

Missionaries used preaching, catechisms, and visual symbols to teach Christian doctrines, often assuming that Native acceptance of baptism or church attendance signaled full conversion and rejection of older beliefs.

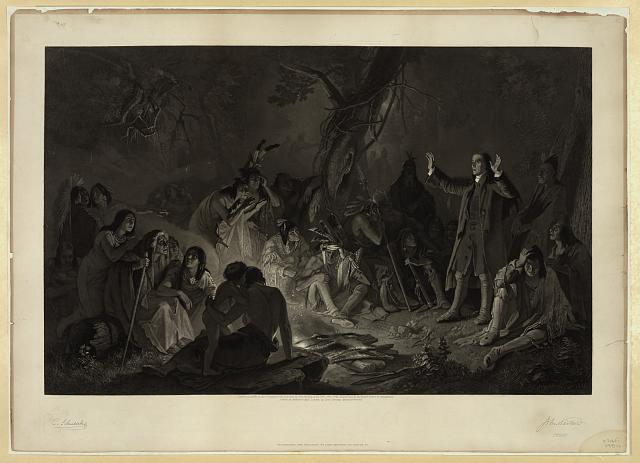

Engraving of the Moravian missionary David Zeisberger preaching to Native Americans around a fire at night. The vivid contrast of light and gesture captures how religious ideas were communicated across cultural boundaries. Although later than the early contact period, it clearly illustrates the spiritual encounters and misunderstanding described in this subtopic. Source.

Technology and Material Culture

Differences in material culture also contributed to misinterpretation. European metal tools, firearms, and ships astonished many Indigenous communities, leading some to ascribe supernatural qualities to European technology. Conversely, Europeans underestimated the sophistication of Indigenous agriculture, architecture, and ecological management, often dismissing Native innovations because they did not resemble European methods.

These contrasting interpretations affected power dynamics:

Native peoples sometimes sought alliances based on access to European goods.

Europeans assumed technological superiority justified territorial claims and coercive labor.

Misunderstanding of Indigenous environmental knowledge led Europeans to misjudge land use and settlement patterns.

Violence, Conflict, and the Escalation of Misunderstanding

As misunderstandings accumulated, small disputes could escalate into conflict. Europeans often interpreted Native resistance as hostility rather than defense of sovereignty, while Indigenous groups viewed European demands as violations of established reciprocal norms and territorial autonomy. Violence was not always the result of intentional aggression; it sometimes arose from failed expectations or misread signals during early encounters.

The Role of Interpreters and Cultural Mediators

Cultural mediators—such as Indigenous translators, European shipwreck survivors, or individuals who lived between communities—played crucial roles in reducing miscommunication. Yet their interpretations could also introduce new distortions, whether through limited vocabulary, competing loyalties, or strategic manipulation. Despite these challenges, mediators shaped key early relationships and had significant influence on diplomacy and trade.

Enduring Significance

The misunderstandings and interpretive challenges of early encounters set patterns that shaped later interactions across North America. From diplomacy and resource disputes to religious missions and cultural exchange, first impressions created expectations and tensions that influenced European-Indigenous relations throughout the colonial period.

FAQ

Many Europeans arrived with a rigid belief that “civilisation” required settled agriculture, written laws, and permanent architecture. When Indigenous societies did not conform to these expectations, Europeans often assumed they lacked political structure or sophistication.

This misjudgement led Europeans to overlook Indigenous systems of governance, ecological management, and diplomacy. It also shaped early policies, as Europeans believed they had a moral or legal justification to “improve” or claim lands inhabited by peoples they deemed less advanced.

Material objects acted as communicative tools, but their meanings differed across cultures.

Europeans frequently viewed objects such as metal tools or beads as commodities with fixed monetary value.

Many Native Americans treated items exchanged during first contact as symbols of relationship-building or spiritual significance.

Misunderstandings arose when Europeans failed to recognise the ceremonial or diplomatic weight of these gifts, while Indigenous groups interpreted European goods as signs of alliance or ongoing reciprocity.

Many Native American societies relied on flexible or consensus-based leadership, where authority varied by context and community. Europeans, however, expected centralised authority resembling monarchy or aristocracy.

As a result, Europeans assumed that an agreement with one leader bound the entire nation or region. This misunderstanding produced frustration when other groups did not follow agreements they had not negotiated, leading Europeans to believe Indigenous partners were unreliable or deceptive.

European societies typically assigned political and economic authority to men, whereas many Indigenous societies had more complementary or overlapping gender roles. Women in some Native communities played central roles in agriculture, diplomacy, or lineage.

Europeans misinterpreted these arrangements as evidence of male weakness or social disorder. This distorted lens shaped early negotiations, as Europeans often ignored or dismissed influential Indigenous women, missing key political relationships and signals.

Interpreters were essential cultural mediators, but their backgrounds shaped how accurately they conveyed meanings.

Some interpreters were captives, traders, or individuals who had lived between communities, giving them partial but not comprehensive cultural knowledge. Others had their own political motives, shaping messages to influence alliances or trade.

As a result, even when vocabulary was accurately translated, deeper concepts—such as territorial sovereignty or reciprocal obligations—were often communicated imperfectly, reinforcing early misunderstandings.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify and briefly explain one reason why early encounters between Europeans and Native Americans were shaped by mutual misunderstanding.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., language barriers, differing diplomatic practices, contrasting worldviews).

1 mark for a brief explanation of how this reason caused misunderstanding.

1 additional mark for a specific example linked to early encounters (e.g., misinterpretation of gift-giving or treaty agreements).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how differing concepts of diplomacy and exchange contributed to conflict during early encounters between Europeans and Native Americans between 1491 and 1607.

Mark scheme:

1–2 marks for describing at least one European diplomatic assumption (e.g., hierarchical leadership, binding written treaties).

1–2 marks for describing at least one Native American diplomatic or exchange practice (e.g., reciprocity, consensus-based leadership, gift-giving as alliance-building).

1–2 marks for explaining how these differences led to tension or conflict, supported by a relevant example (e.g., disputes over land ownership, breakdown of trade alliances).