AP Syllabus focus:

‘Europeans and Native Americans held divergent worldviews about religion, gender roles, family, land use, and power.’

Early encounters between Europeans and Native Americans revealed fundamentally different beliefs about spirituality, land, social roles, and political authority, shaping cooperation, conflict, and cultural transformation throughout early American history.

Religion and Spiritual Worldviews

European and Native American societies possessed contrasting understandings of spiritual authority, sacred power, and the relationship between humans and the natural world. These differences shaped diplomacy, trade, and conflict from the first moments of contact.

European Christian Worldviews

European explorers and settlers entered the Americas with a deeply rooted Christian cosmology, emphasizing monotheism, salvation, and hierarchical religious authority. Many believed in the universal truth of Christianity and viewed missionizing as both a moral obligation and a justification for colonization.

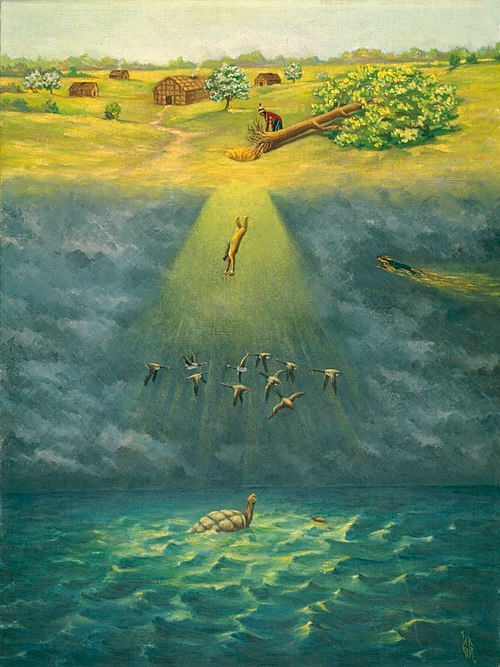

Sky Woman illustrates a Haudenosaunee creation story in which a woman falls from the sky and the animals help create the land, often called Turtle Island. The image highlights an Indigenous worldview in which the earth, water, and animals are active spiritual participants rather than passive resources. Although it focuses on one nation’s traditions, it helps visualize how Native religions tied cosmology directly to land and community. Source.

Monotheism: The belief in a single, all-powerful deity who governs the universe and establishes moral law.

European Christians often interpreted Native American spiritual traditions through a Eurocentric lens, characterizing them as “pagan,” “heathen,” or “superstitious.” The presence of priests, missionaries, and religious orders—especially among the Spanish—reinforced expectations that Indigenous peoples should convert and accept Christian authority.

Native American Spiritual Frameworks

Native American groups varied widely in belief and ceremony, yet many shared an emphasis on spiritual interconnectedness between humans, animals, and the natural world. Sacred power was frequently understood as dispersed, dynamic, and tied to specific landscapes or rituals rather than housed in a single institution.

Spiritual power could inhabit animals, plants, natural forces, and ancestral beings.

Ritual specialists, such as shamans or healers, mediated relationships between communities and spiritual forces.

Religion was often woven into daily life rather than separated into distinct religious institutions.

These differences contributed to misunderstandings, as Europeans assumed Native peoples lacked “proper” religion, while Native communities perceived Europeans as disconnected from the land and its spirits.

Land, Property, and Environmental Use

Divergent conceptions of land ownership and environmental rights were among the most significant sources of tension in early encounters.

European Notions of Land Ownership

European societies embraced private property, legal contracts, and the transfer of land through written agreements. Land was considered a commodity that could be bought, sold, inherited, and fenced. Agricultural “improvement” was seen as proof of rightful ownership.

Private Property: A system in which individuals or groups hold legal rights to possess, use, and transfer land or goods.

This perspective encouraged Europeans to view land not actively farmed in European style as “unused” or “vacant,” legitimizing colonization in their eyes.

Indigenous Concepts of Land Stewardship

Native American societies generally practiced communal land use, meaning land was collectively accessed and managed by kin networks, villages, or nations. While specific plots might be used by families or clans, the idea of permanently transferring large tracts through sale was foreign.

Key elements of Indigenous land use included:

Seasonal movement to maximize hunting, fishing, and agricultural cycles.

Respect for environmental balance rather than extractive ownership.

Sacred attachment to particular rivers, mountains, forests, or ceremonial spaces.

European failure to grasp these principles contributed to recurrent disputes, broken treaties, and violent confrontations over territory.

Gender Roles and Family Structures

Differing expectations regarding gender, labor, and kinship shaped cross-cultural misunderstandings and European judgments about Native societies.

European Patriarchal Models

Europeans followed a patriarchal system in which men held primary political and economic authority. Women’s legal status was often tied to their husbands or fathers, and inheritance typically passed through the male line. European observers frequently evaluated Indigenous societies through this patriarchal framework, assuming that male authority was the universal norm.

Native American Gendered Labor and Kinship

Many Native groups structured labor, political participation, and family relations differently. In numerous societies—especially in the Eastern Woodlands—women played central roles in agriculture, property rights, and diplomacy.

Examples include:

Women cultivating maize, beans, and squash, giving them authority over agricultural fields.

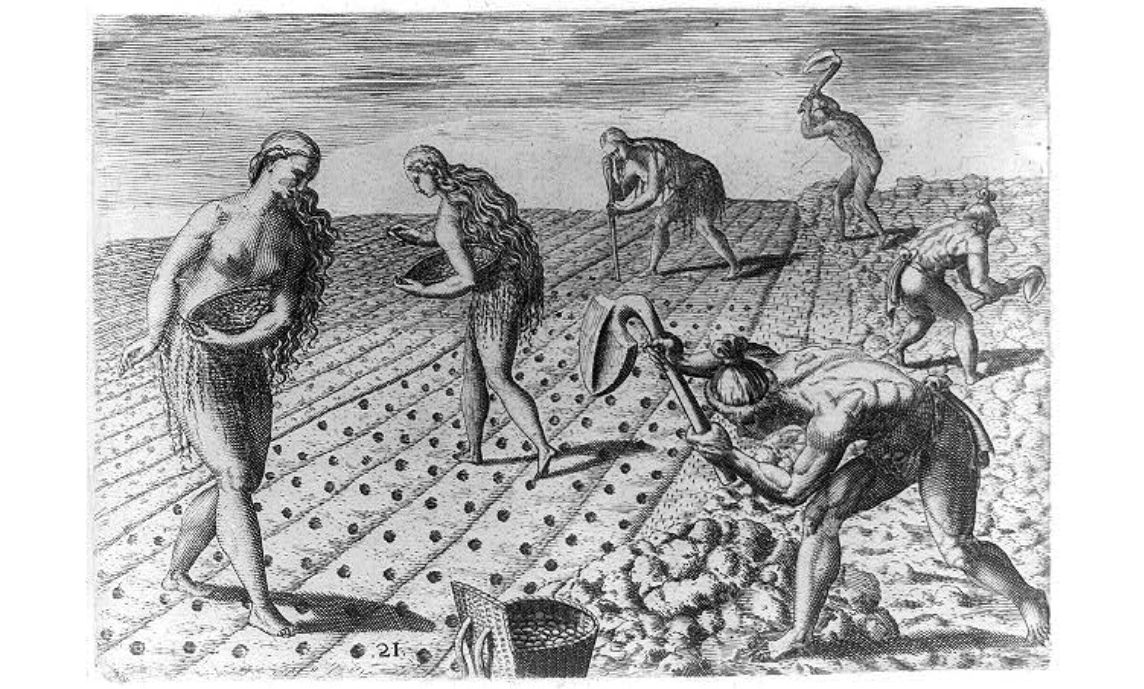

This engraving shows Timucua men loosening the soil while women plant maize and beans in sixteenth-century Florida. It visually reinforces how, in many Native societies, women’s agricultural labor underpinned community survival and political authority. The scene is region-specific, but the gendered farming pattern is broadly representative of Indigenous agricultural societies discussed in the notes. Source.

Matrilineal kinship systems in which lineage and inheritance followed the mother’s line.

Female participation in council decisions or leadership roles in some communities.

Because Europeans equated women’s agricultural labor with low status, they often misinterpreted these systems as signs of Native “backwardness,” overlooking the political and economic power Indigenous women wielded.

Power, Authority, and Political Structures

European and Native political systems differed profoundly, shaping how each group negotiated agreements and perceived legitimacy.

European Centralized Authority

European monarchies and emerging nation-states emphasized centralized authority, written law, and rigid hierarchies. Diplomacy was conducted through official representatives, and political decisions were expected to bind entire populations.

This engraving shows Moravian missionary David Zeisberger preaching to a group of Native Americans gathered around a fire. The composition emphasizes the missionary as a central authority figure, capturing how European Christianity was presented as a universal truth expected to be adopted by Native peoples. Although from a slightly later era, it visualizes conversion dynamics rooted in early encounters. Source.

Native Consensus and Distributed Authority

Many Native polities exercised authority through consensus-building, clan leadership, or councils rather than a single centralized ruler.

Chiefs often held influence, not coercive power.

Political authority varied by region, with some groups more hierarchical and others highly decentralized.

Agreements typically required broad community consent, not unilateral decision-making.

These differences frequently led Europeans to assume Native leaders lacked real authority, while Native communities were puzzled by European insistence on singular rulers and rigid legal agreements.

Cultural Consequences of Divergent Worldviews

The clash between European and Indigenous worldviews produced long-lasting consequences. It shaped early diplomacy, trade relationships, and conflict patterns; influenced missionary efforts; and structured the evolving power dynamics of colonization. Misunderstandings over religion, labor, gender, and land contributed at every stage to friction, negotiation, adaptation, and resistance throughout the period from 1491 to 1607.

FAQ

European envoys typically expected to negotiate with a single authoritative leader, mirroring monarchic or centralised political traditions. When no such figure existed, Europeans often appointed or favoured an individual who appeared most influential, even if that person did not hold coercive power.

This created diplomatic misunderstandings because many Native nations relied on consensus-based decision-making. Treaties agreed by one leader might not be recognised by the wider community, causing Europeans to interpret Indigenous diplomacy as unreliable or resistant.

European observers often evaluated unfamiliar rituals through a strict Christian framework, leading them to label ceremonies involving animal spirits, seasonal cycles, or sacred landscapes as idolatry or superstition.

Indigenous ceremonies also blurred distinctions between daily life and spiritual practice, making it difficult for Europeans to identify a separate religious sphere. As a result, they underestimated the political and social meaning of rituals that reinforced alliances, legitimised leaders, or ensured environmental balance.

European men expected Native men to take part in labour familiar to Europeans, such as plough agriculture or wage-based tasks, and were surprised when hunting or diplomacy occupied much of their time.

Native women often controlled food production and material goods such as corn, pottery, and woven items. This meant women became crucial intermediaries in early trade, a role Europeans rarely recognised as political or economic authority.

Many Native nations structured kinship around clans, extended families, or matrilineal lines, shaping obligations, inheritance, and political representation.

Because kinship determined who could speak for a group, Europeans sometimes unknowingly violated expectations by addressing the wrong individuals or ignoring clan relationships. This could weaken alliances or generate offence, especially where marriage or adoption into clans formed part of diplomatic tradition.

Indigenous territorial claims often centred on use rights, seasonal movement, and spiritual relationships to specific places rather than fixed, surveyed borders.

Europeans, accustomed to mapped boundaries and exclusive ownership, assumed that land not permanently settled or fenced was unclaimed. This led them to disregard Indigenous territorial markers such as rivers, hunting routes, or sacred spaces, escalating disputes and undermining trust.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one major difference between European and Native American views of land use in the period 1491–1607, and briefly explain why this difference created friction during early encounters.

Mark scheme (3 marks total)

1 mark for correctly identifying a difference (e.g., Europeans emphasised private ownership; Native societies practised communal stewardship).

1 mark for explaining how this difference affected interactions (e.g., Europeans assumed land not farmed in European style was ‘unused’).

1 mark for linking this misunderstanding to friction (e.g., disputes over treaties, territory, or claims of rightful occupation).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how differing religious and gender worldviews shaped early interactions between Europeans and Native Americans in the period 1491–1607. In your answer, refer to specific contrasts in beliefs and social structures.

Mark scheme (6 marks total)

Up to 2 marks for accurately describing differences in religious beliefs (e.g., European monotheism and missionary aims versus Indigenous spiritual interconnectedness).

Up to 2 marks for explaining differences in gender roles and family organisation (e.g., European patriarchy versus Indigenous matrilineal or women-centred agricultural systems).

Up to 1 mark for linking these contrasts to cooperation or conflict in early encounters (e.g., European misunderstandings of Indigenous women’s authority).

Up to 1 mark for use of specific examples or details drawn from the topic (e.g., missionaries expecting conversion; Europeans misinterpreting Native practices as ‘pagan’).