AP Syllabus focus:

‘European rivals and American Indians competed for resources; this competition encouraged trade and industry and also led to conflict in the Americas.’

Competition among European powers and American Indians for land, trade, and natural resources shaped early North American colonial dynamics, generating both economic opportunity and recurrent conflict across regions.

Imperial Competition and the Struggle for Resources

European Rivalries in North America

European colonization in the 17th and early 18th centuries unfolded within a broader imperial contest among Spain, France, the Netherlands, and England. Each empire pursued distinct goals but competed intensely for control of the continent’s abundant furs, fertile land, minerals, and strategic waterways. This imperial rivalry created shifting alliances, fueled wars, and reshaped Indigenous power dynamics.

As European powers sought advantage, they introduced economic systems that tied colonial development to international trade. Rivalries in Europe, such as Anglo-French conflicts, extended into North America, where both countries attempted to secure valuable regions like the St. Lawrence Valley, Great Lakes, and Chesapeake.

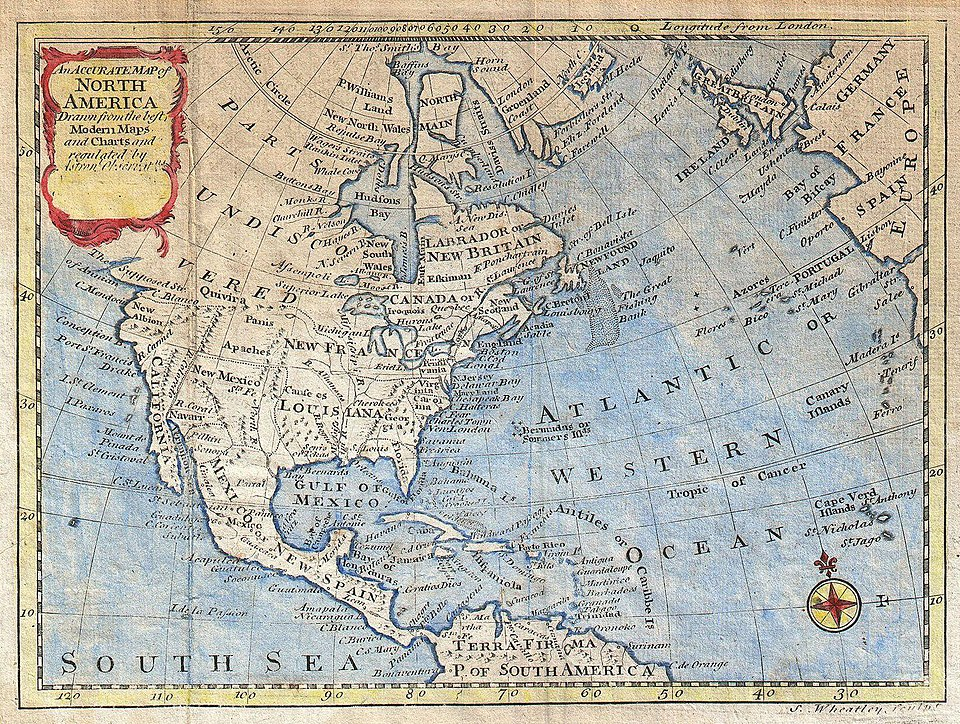

This eighteenth-century map shows British, French, and Spanish claims across North America, illustrating major contested regions that shaped imperial rivalry. It highlights areas such as Canada, Louisiana, and the Caribbean that became centers of trade and conflict. The map contains additional period details beyond the AP curriculum but helps visualize European perceptions of North American geography. Source.

American Indian Agency and Strategic Partnerships

Indigenous nations were not passive participants but central actors who shaped the competitive landscape. They often leveraged European rivalries to pursue their own goals, including access to trade goods, protection from enemies, and territorial security. Nations such as the Iroquois Confederacy strategically negotiated with multiple European powers to maintain autonomy and strengthen their political influence.

Iroquois Confederacy: A powerful alliance of five (later six) northeastern Indigenous nations that exercised significant diplomatic and military influence in colonial-era North America.

Diplomatic flexibility enabled Indigenous groups to sustain a degree of independence, although the long-term effects of competition—including epidemic disease and land loss—would ultimately weaken many of these nations.

This painting shows Governor Frontenac of New France participating in a war dance alongside Indigenous allies in 1690, emphasizing the central role of Native-European alliances in imperial conflict. It reflects how diplomacy and military cooperation shaped power dynamics in northeastern North America. The artwork includes dramatized elements beyond the AP scope but effectively illustrates alliance-building in the colonial era. Source.

Trade, Resources, and the Growth of Industry

Access to natural resources drove intercolonial relations and shaped emerging industries. The fur trade, dominated initially by the French and Dutch, created economic networks connecting Native hunters to European markets. English settlers, arriving in larger numbers, emphasized agriculture and territorial expansion but soon recognized the value of participating in regional trade systems.

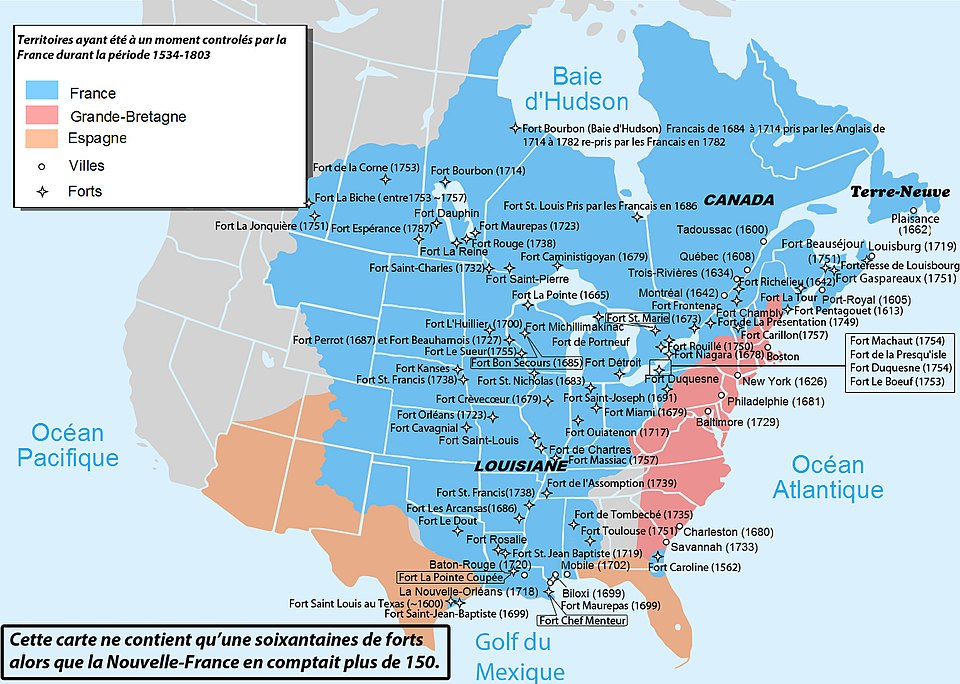

This map illustrates French territorial claims across Canada, the Great Lakes, and the Mississippi Valley, highlighting regions central to the fur trade. It visually reinforces why these areas became focal points of competition among European empires. The map includes broader chronological coverage than the AP period but remains useful for understanding the geographic scale of French influence. Source.

Competition for resources encouraged:

Expansion of commercial networks, linking European ports to colonial regions and Indigenous suppliers.

Development of port cities such as Boston, New Amsterdam, and Quebec.

Intensification of the fur trade, which placed mounting pressure on animal populations and Indigenous hunting territories.

Rival merchant and charter companies, including the Dutch West India Company and English joint-stock enterprises.

European economic ambition forced growing engagement with Native communities, as neither group could initially dominate resource extraction without cooperation.

Conflicts Rooted in Resource Competition

Competition for land and trade frequently escalated into conflict. Both Europeans and Indigenous nations sought control of strategic territory, leading to wars that reflected wider imperial struggles.

Major conflict patterns included:

French–English rivalry, culminating in tensions that foreshadowed the later French and Indian War.

Dutch–English rivalry, particularly over lucrative trade in the Hudson River region.

Intertribal conflict intensified by European weapons, as groups armed by one power fought rivals aligned with another.

Territorial clashes, as English settlers encroached on Indigenous lands to expand tobacco agriculture.

These violent encounters disrupted longstanding Indigenous political arrangements. For example, wars involving the Iroquois and their neighbors often stemmed from competition over hunting grounds depleted by the fur trade.

Indigenous Adaptation and Changing Power Balances

American Indians responded to imperial rivalry with adaptation, resistance, and shifting alliances. Access to European firearms, metal tools, and textiles altered economic and military capabilities, but increasing dependence on European goods risked undermining Indigenous autonomy.

Changes included:

Transformation of traditional economies, as hunting intensified to meet European demand for pelts.

Reorientation of settlement patterns, with some groups relocating to remain close to trade routes.

Fluctuating diplomatic power, especially for nations able to play Europeans against one another.

Some Indigenous groups gained influence early in the period, but sustained competition—combined with population decline from disease—eventually weakened many communities.

Environmental and Demographic Consequences

The struggle for resources reshaped the environment and populations of North America. Intensified fur harvesting, forest clearing, and European agricultural practices altered ecosystems. Meanwhile, repeated conflicts and epidemic disease dramatically reduced Indigenous populations, transforming the balance of power between Europeans and Native nations.

Environmental and demographic patterns emerging from this competition included:

Overhunting of beaver and other fur-bearing animals, leading to ecological shifts.

Deforestation associated with expanding English settlement.

Population collapse among Indigenous communities, which hindered resistance to colonial expansion.

Migration and consolidation of surviving Indigenous groups seeking new alliances or safer territories.

Broader Significance of Imperial Competition

The continuous struggle for resources produced a colonial world defined by both opportunity and instability. Economic competition spurred early industry and transatlantic trade, while overlapping land claims ignited recurring conflict. These patterns laid foundational tensions in North America and shaped social, political, and economic structures that would continue into later periods of colonial and imperial history.

FAQ

The fur trade heightened competition between Indigenous groups as they vied for access to European goods, which became increasingly essential for diplomacy and warfare.

Some nations gained temporary advantages by aligning with particular European powers, but these shifts also intensified rivalries over hunting territories depleted by overharvesting.

This contributed to regional instability, prompting migrations, new alliances, and, in some cases, the consolidation of smaller groups into larger political entities for protection.

The Dutch focused on concentrated trading posts rather than widespread settlement, allowing them to efficiently control profitable exchanges with Indigenous nations.

Their emphasis on commercial partnerships made them valuable allies for Native groups seeking to counterbalance French or English influence.

This strategic flexibility gave the Dutch disproportionate influence in parts of the Northeast until their holdings were taken over by the English in the mid-seventeenth century.

The interior offered rich supplies of beaver and other fur-bearing animals essential for European fashion markets, making the region a major commercial target.

It also contained extensive river systems—such as the St Lawrence, Great Lakes, and Mississippi—that acted as natural trade corridors.

These waterways enabled efficient transport of goods, encouraging France, England, and their Indigenous partners to compete for influence over key portage routes and settlement sites.

European powers constructed forts to secure trade networks, protect colonial claims, and deter rival empires from encroaching on strategic areas.

Many were built at existing Indigenous crossroads, reinforcing Native communities’ importance in regional geopolitics.

Common functions of these sites included:

Serving as storage centres for furs and trade goods

Acting as diplomatic hubs for treaty-making

Housing small garrisons to oversee territorial disputes

These posts often became focal points for both cooperation and conflict.

Indigenous nations determined when and how Europeans could traverse, trade within, or settle on particular lands, often granting permission in exchange for weapons, trade goods, or political support.

Through selective alliances, Native leaders could delay or redirect European expansion, especially in regions where no single empire had overwhelming military or demographic advantage.

Diplomatic practices included gift-giving, ritual adoption, and treaty negotiation—mechanisms that required Europeans to participate in Indigenous political customs to maintain access to resources.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which European competition for resources influenced relations between colonists and American Indians in the seventeenth century.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid influence (e.g., competition for furs led to increased trade with Indigenous nations).

1 mark for explaining how this affected relations (e.g., alliances formed as Europeans sought Native partners to secure trade).

1 mark for providing specific, accurate detail (e.g., French reliance on Algonquian-speaking nations for fur supply strengthened diplomatic ties).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which imperial rivalry shaped patterns of conflict in North America between European powers and American Indians during the period 1607–1754.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for a clear argument addressing extent (e.g., rivalry was the primary driver of conflict, or it played a significant but not exclusive role).

1–2 marks for specific evidence of imperial rivalry shaping conflict (e.g., Anglo-French competition escalating tensions in the Great Lakes region; Dutch and English competition along the Hudson River).

1–2 marks for accurate reference to American Indian agency (e.g., Iroquois leveraging European rivalry to strengthen their position, conflicts resulting from shifting alliances).

1 mark for recognising additional or limiting factors (e.g., disease, land pressure from English settlers, internal Native rivalries).