AP Syllabus focus:

‘In the 17th century, early British colonies developed along the Atlantic coast with regional differences shaped by environmental, economic, cultural, and demographic factors.’

The early British colonies displayed striking diversity as settlers adapted to distinct climates, economies, and social structures, producing regional patterns that laid foundations for later American development.

Environmental Foundations of Regional Diversity

Regional variation in the British colonies emerged largely from contrasts in geography and climate. These environmental realities shaped settlement strategies, agricultural practices, and demographic composition. Colonists entering New England confronted rocky soils, short growing seasons, and abundant timber and fish, limiting plantation-style agriculture. By contrast, the Chesapeake and southern regions featured fertile land, navigable rivers, and long growing seasons, enabling commercial crop production.

Environmental Factors and Settlement Outcomes

New England: Cold climate, thin soil, dense forests.

Middle Colonies: Moderate climate, fertile river valleys, navigable waterways.

Chesapeake/South: Hot, humid climate, rich soil ideal for cash crops.

These differences encouraged colonists to form distinct relationships with the land and one another.

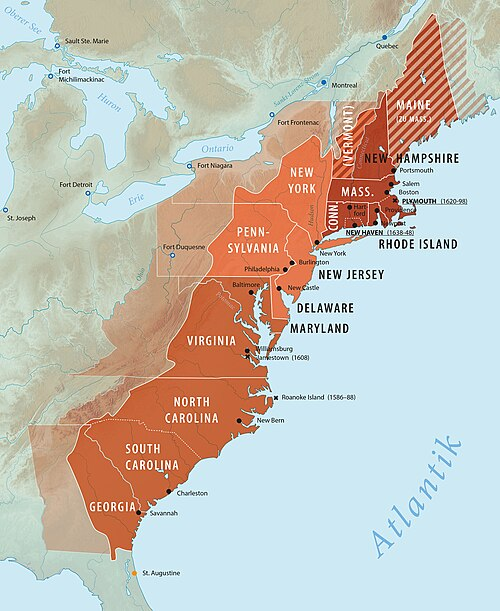

This map shows the Thirteen Colonies organized into New England, Middle Atlantic, and Southern regions, highlighting geographic foundations for regional diversity. The color-coding reinforces how location and environment shaped colonial economies and settlement patterns. The shaded relief and state outlines provide additional geographic context beyond the syllabus but aid orientation. Source.

Demographic Patterns and Community Structure

Demographic factors—family composition, migration motives, and population diversity—strongly influenced colonial life. New England migration was dominated by entire family units, often driven by religious objectives. In contrast, the Chesapeake initially attracted mostly young, single men seeking economic opportunity.

Indentured Servitude: A labor system in which individuals worked for a fixed term in exchange for passage to the colonies, food, and shelter.

In the decades following settlement, these demographic realities shaped community stability. New England’s balanced sex ratio and family-centered migration supported population growth through natural increase. The Chesapeake, with its gender imbalance and higher mortality, developed more slowly and experienced greater social instability in the early years.

A separate migration pattern emerged in the Middle Colonies, where diverse European groups—including Dutch, German, Swedish, and Scots-Irish settlers—created ethnic and religious pluralism. This population mixture contributed to flexible social structures and relatively tolerant community norms.

Economic Systems and Labor Patterns

Economic pursuits varied widely across regions, driven by environments and settler goals. New England, unable to sustain large-scale plantation agriculture, created a mixed economy blending small-scale farming, shipbuilding, fishing, and Atlantic commerce. Middle Colonies produced robust export crops, especially wheat and other grains, supporting growing port cities such as Philadelphia.

In the Chesapeake and southern regions, tobacco became the dominant cash crop, shaping labor needs and land use patterns. The tobacco economy required intense labor inputs, first met through indentured servants and later through the growing reliance on enslaved Africans. These labor transitions intensified regional divergence as slavery expanded in plantation zones but remained far less central in New England and the Middle Colonies.

Regional Economic Characteristics

New England: Mixed agriculture, maritime trade, artisan production.

Middle Colonies: Grain exports, commercial agriculture, port-driven commerce.

Chesapeake/South: Plantation agriculture centered on tobacco; rising dependence on enslaved labor.

Economic specialization created distinct social stratifications: a merchant elite in New England, wealthy landowning families in the Middle Colonies, and a powerful planter aristocracy in the Chesapeake and southern regions.

Cultural and Religious Influences

Cultural and religious factors further differentiated the regional societies. New England colonists, especially Puritans, emphasized communal discipline, education, and religious conformity. Their commitment to building a “godly society” influenced town planning, schooling, and local governance.

Puritanism: A reform movement within English Protestantism that sought to “purify” the Church of England and build morally disciplined communities.

In the Middle Colonies, cultural diversity fostered religious tolerance. Quakers in Pennsylvania promoted principles such as pacifism, egalitarianism, and inclusive political participation. This encouraged patterns of pluralism not found elsewhere in the colonies.

A sentence after the definition ensures correct formatting flow and reinforces how culture interacted with political and economic forces across regions.

Political Development and Self-Governance

Political structures varied as colonies adapted English traditions to local conditions. New England’s town-centered settlement pattern fostered town meetings, promoting participatory local governance. Citizens—typically male property holders—debated community concerns, reflecting Puritan communal ideals.

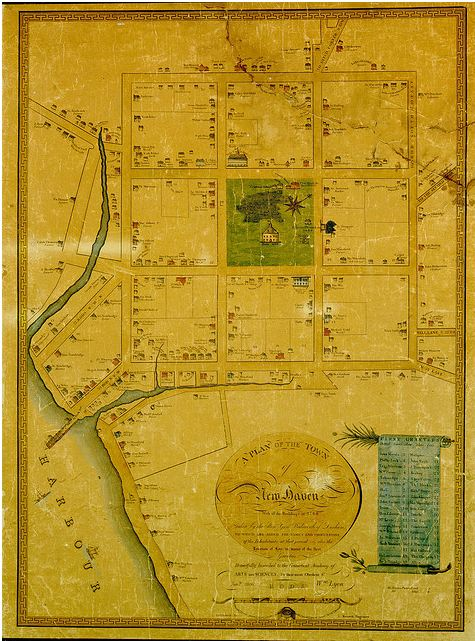

This plan of New Haven in 1748 shows a classic New England town layout centered on a communal green bordered by public buildings and homes. The image visually reinforces how settlement patterns encouraged regular civic participation through town meetings. It includes additional historical details—such as labeled property lots and harbor placement—that extend beyond the APUSH syllabus but support spatial understanding. Source.

The Middle Colonies developed a blend of municipal governance and representative assemblies shaped by diverse populations. In the Chesapeake and southern colonies, county governments and representative assemblies such as the Virginia House of Burgesses emerged, but political power concentrated among elite planters controlling vast tracts of land and labor.

Key Patterns of Colonial Governance

New England: Town meetings, strong local autonomy.

Middle Colonies: Representative assemblies shaped by pluralism.

Chesapeake/South: County-level administration dominated by wealthy elites.

These political differences reflected broader regional cultures—collective decision-making in New England, diversity-driven negotiation in the Middle Colonies, and hierarchical authority in plantation societies.

Interconnectedness and Divergence

Although all British colonies shared ties to the Crown and the Atlantic economy, their regional economies, demographics, and cultural foundations created unique colonial identities. Environmental realities shaped settlement and economic patterns, while migration motives and cultural backgrounds molded community institutions. Together these forces produced a patchwork of distinct colonial regions whose differences deepened over the 17th century and influenced future developments in British North America.

FAQ

New England typically allocated land collectively, with town authorities granting plots based on community needs, social standing, and family size. This supported clustered settlement and communal institutions.

In the Chesapeake and southern regions, land was often distributed through headright systems, encouraging large, privately owned tracts. This system reinforced dispersed settlement, economic inequality, and the growth of plantation elites.

Regional geography influenced patterns of trade, conflict, and diplomacy. New England tribes engaged in local trade networks and faced rapid settlement pressure, leading to more frequent territorial disputes.

In the Middle Colonies, diverse European powers had earlier established trade relationships, allowing relative coexistence and negotiated land agreements. Southern colonies’ expansion into fertile river valleys intensified contestation over land and resources.

Puritan-led migration created strong religious uniformity in New England, where civic and religious life were intertwined. Dissenters were often expelled or encouraged to form separate settlements.

The Middle Colonies welcomed varied European migrants from the outset, producing pluralistic societies supported by legal toleration.

Southern colonies had Anglican majorities but weaker institutional enforcement, allowing local variations in practice and reduced communal religious influence.

New England’s healthier climate resulted in lower mortality, longer life expectancy, and stable family structures. This supported organic population growth and cohesive communities.

Chesapeake and southern colonies experienced high disease burdens, which reduced life spans and slowed the establishment of stable family networks. High mortality contributed to social fluidity, labour instability, and heavy reliance on imported workers.

New England’s abundant timber and coastal fisheries enabled shipbuilding, maritime trade, and a diversified economic base distinct from plantation agriculture.

The Middle Colonies’ fertile soil supported grain exports, reinforcing their role as the colonies’ primary breadbasket.

The Chesapeake’s optimal conditions for tobacco fostered monoculture, plantation expansion, and rising demand for bound labour.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks):

Identify two factors that contributed to regional diversity among the early British colonies in the 17th century.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks:

• 1 mark for each accurately identified factor (maximum 2 marks).

Acceptable answers include: climate variation, soil fertility, availability of natural resources, differing migration patterns, demographic composition, religious motivations, or economic goals.

• 1 additional mark for a brief explanation of how one factor contributed to regional diversity.

Question 2 (4–6 marks):

Explain how environmental and demographic differences shaped the development of contrasting social and economic structures in New England and the Chesapeake during the 17th century.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award up to 6 marks:

• 1–2 marks for describing environmental differences (e.g., short growing seasons in New England vs. fertile land in the Chesapeake).

• 1–2 marks for describing demographic differences (e.g., family-based migration to New England vs. predominantly young, single men in the Chesapeake).

• 1–2 marks for explaining how these differences produced contrasting social and economic structures (e.g., New England’s mixed economy and town-based communities vs. Chesapeake’s plantation economy and dispersed settlements).