AP Syllabus focus:

‘Political, social, cultural, and economic exchanges with Great Britain strengthened ties to Britain but also encouraged resistance to Britain’s control.’

Atlantic exchanges tied British colonists into a wider imperial system, fostering shared identities and economic interdependence while simultaneously stimulating colonial frustrations that gradually nurtured resistance to British authority.

Transatlantic Connections and the Formation of Imperial Bonds

Throughout the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the British Atlantic world intensified through expanding networks of migration, commerce, communication, and political oversight. These interactions wove the colonies into a broader imperial community, reinforcing loyalty to Britain even as emerging tensions revealed the limits of imperial cohesion.

Political Exchanges and the Reproduction of English Institutions

Colonists brought English political traditions with them and adapted these ideas to New World circumstances. The English common law tradition, representative government, and expectations of “rights of Englishmen” shaped how colonial societies functioned.

Rights of Englishmen: The traditional liberties held by English subjects, including due process, representative consent, and limits on arbitrary authority.

These political expectations made colonists highly sensitive to policies suggesting excessive control. Nevertheless, for much of the period, the Atlantic political relationship worked to reinforce imperial unity. Colonial elites often sought British approval, and imperial officials assumed that shared traditions and loyalty would maintain stability. Regular correspondence, the appointment of royal governors, and the oversight of colonial charters knitted the colonies into the imperial system. Yet these very channels also became conduits for political disputes when colonists resisted attempts to consolidate authority.

Religious and Cultural Connections Across the Atlantic

Cultural exchanges also played a major role in sustaining bonds with Britain. The flow of ministers, books, and ideas linked the colonies to transatlantic religious debates. Circulating sermons and pamphlets connected colonists to broader Protestant discussions about morality, governance, and community.

Colonial colleges, printing houses, and learned societies drew heavily from British intellectual currents, reinforcing cultural alignment. Participation in a shared Anglophone Protestant culture contributed to colonists’ sense of belonging within an extended British world.

However, cultural circulation also empowered colonists to critique imperial policies. British political and theological writings provided language for evaluating authority, especially when colonists felt their liberties were threatened.

Economic Interdependence and Tensions in the Atlantic System

Economic ties formed the core of imperial integration.

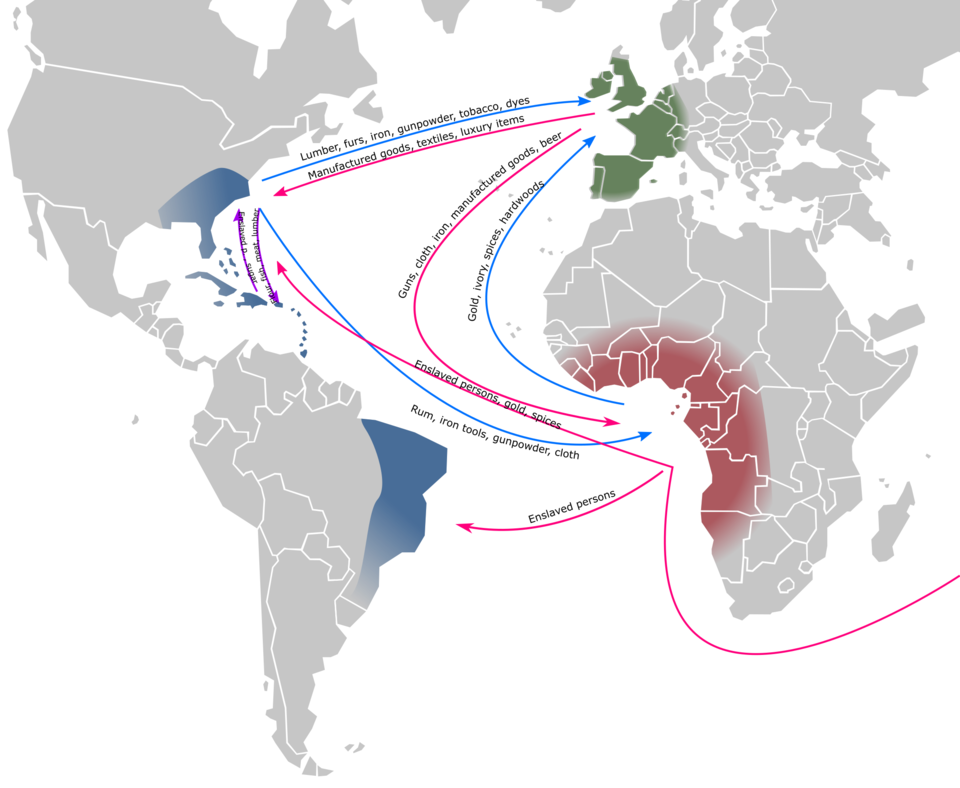

A color map of the Atlantic world shows the major routes of the Atlantic Triangular Trade, with arrows indicating flows of goods, capital, and enslaved people between Europe, West Africa, and the Americas. It illustrates how European empires, including Britain, integrated their colonies into a commercial system that moved sugar, tobacco, manufactured goods, and enslaved laborers across the ocean. The map also includes Spanish and Portuguese routes and emphasizes the slave trade, which extends beyond this subsubtopic but deepens understanding of the economic foundations of Atlantic exchanges. Source.

British mercantilist policies assumed that colonies existed to supply raw materials and consume British manufactured goods. These policies were embodied in the Navigation Acts, which attempted to structure trade in Britain’s favor.

Colonial merchants operated within this system because it offered access to British markets, credit networks, and shipping protection. These benefits deepened colonial reliance on the empire.

Yet restrictive trade rules also created friction. Many colonial merchants viewed these regulations as constraints on economic opportunity. This tension produced widespread smuggling and negotiations for exemptions or favorable enforcement. The Atlantic economy thus functioned through a combination of cooperation, evasion, and periodic crackdowns.

Social Mobility and Changing Colonial Attitudes

Social and demographic changes generated additional layers of connection and conflict. The steady flow of immigrants, including English, Scottish, and Welsh settlers, reinforced British cultural influence. At the same time, increasing prosperity in port cities—fueled by Atlantic commerce—allowed some colonists to accumulate wealth and social standing.

As colonial elites grew more confident, they sometimes viewed British interference as an obstacle rather than a support. They embraced British ideals of liberty and property rights while asserting that these principles justified greater local autonomy.

Resistance Emerging from Atlantic Exchanges

Although the colonies were deeply embedded in the British world, these same exchanges planted the seeds of resistance by exposing colonists to multiple sources of imperial authority, commercial regulation, and cultural comparison.

Conflicts over Imperial Control

Britain’s attempts to streamline colonial governance often clashed with colonists’ expectations of autonomy. Political quarrels erupted when governors attempted to assert prerogatives that legislatures considered excessive. Disputes over taxation, military defense, and land policy became flashpoints.

Colonial leaders insisted that political participation and consent were essential components of legitimate rule—principles they drew from both English tradition and Atlantic political discourse. These disagreements encouraged colonists to develop a sharper sense of their own political identity.

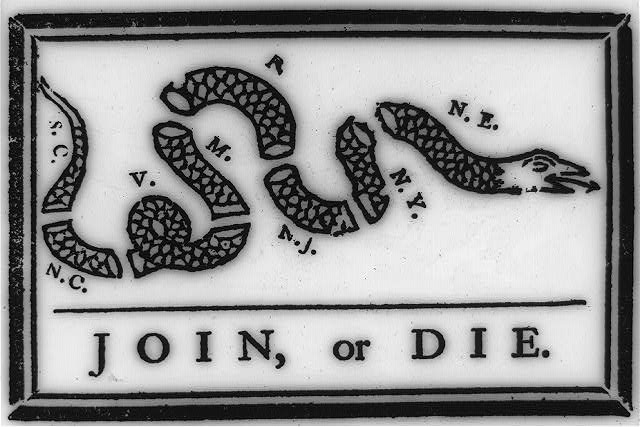

This woodcut cartoon, titled “Join or Die,” shows a segmented snake representing the British American colonies, paired with the warning “JOIN, or DIE.” Published in 1754 in Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette, it urged colonial unity during the French and Indian War while relying on shared transatlantic print culture. The image predates later revolutionary resistance but reflects the early development of a collective colonial identity and the habit of critiquing imperial authority in print. Source.

The Role of Commerce in Encouraging Resistance

Economic exchanges further shaped resistance. When British policies restricted trade or imposed duties, colonial merchants mobilized against imperial interference.

Key dynamics included:

Dependence on British credit, which limited local financial autonomy.

Frustration with trade restrictions that prevented access to non-British markets.

Conflicts over customs enforcement, especially when imperial officials intensified oversight.

These pressures strengthened colonial arguments for freer trade and local economic control.

Cultural Exchange as a Catalyst for Critical Thought

The same transatlantic circulation of books, pamphlets, and sermons that reinforced cultural ties also equipped colonists with intellectual tools to challenge imperial authority. Political writings that discussed natural rights, just governance, and corruption resonated deeply within colonial debates.

By engaging with these ideas, colonists used British intellectual traditions to articulate critiques of British policy. Thus, cultural exchange both affirmed British identity and inspired opposition to British control.

Local Adaptations and the Push Toward Autonomy

Ultimately, the colonies’ integration into the British Atlantic world strengthened ties but created expectations of autonomy that imperial officials struggled to manage.

Colonists adapted British institutions to local conditions, resulting in distinctive political cultures that valued self-rule, commercial independence, and community-based governance. As these adaptations solidified, colonists grew more assertive in defending what they saw as their rightful liberties, even as they continued to identify strongly with Britain.

FAQ

Colonial elites benefited from British economic protection, social prestige and access to imperial markets. Many viewed themselves as culturally British.

However, they increasingly found that imperial officials misunderstood local conditions, leading to conflicts over taxation, land grants and trade enforcement.

This duality created a mindset where elites defended their rights as British subjects while simultaneously criticising decisions made in London.

Cheap pamphlets, sermons and newspapers became more widely available, especially in port towns, allowing many colonists to engage with political and religious debates.

Key effects included:

• Greater literacy driven by Protestant traditions

• Broader access to arguments about governance and rights

• Emergence of public discussion in taverns, churches and marketplaces

This widened participation contributed to more assertive attitudes toward imperial authority.

New England merchants often resisted trade restrictions because smuggling and Atlantic commerce were central to their prosperity.

Southern planters generally depended on British credit and shipping for their staple crops, making them more cautious about open resistance.

These regional differences shaped colonial politics and influenced which groups pushed hardest for local autonomy when imperial enforcement tightened.

Transatlantic religious debates often challenged established authority and emphasised personal conscience, providing colonists with intellectual tools for questioning political power.

Visiting ministers introduced reformist or dissenting ideas that encouraged colonists to scrutinise both church and state leadership.

As congregations discussed these ideas, they developed habits of collective decision-making that later translated into political arenas, reinforcing arguments for self-governance.

Faster and more reliable shipping routes meant newspapers, pamphlets and letters circulated more quickly, exposing colonists to British political debates and religious controversies.

This increased flow of information encouraged colonists to compare their situation with developments in Britain, sharpening their awareness of political rights and expectations.

It also fostered transatlantic networks of merchants, ministers and intellectuals who shared ideas and strategies for influencing imperial policy.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which economic exchanges with Great Britain strengthened ties between the colonies and the British Empire during the seventeenth or early eighteenth century.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which economic exchanges with Britain strengthened imperial ties.

1 mark: Identifies a valid economic exchange (e.g., Navigation Acts, access to British markets, credit networks).

2 marks: Provides a brief explanation of how this exchange strengthened ties (e.g., mutual commercial dependence, British protection of trade routes).

3 marks: Gives a clear and specific explanation showing cause and effect (e.g., how reliance on British manufactured goods or shipping integrated colonial economies into the imperial system).

(4–6 marks)

Analyse how transatlantic political and cultural exchanges both reinforced colonial loyalty to Britain and encouraged emerging resistance to British authority in the period before 1754.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how political and cultural exchanges reinforced loyalty yet also encouraged resistance before 1754.

4 marks: Identifies at least one political and one cultural exchange and links them to either loyalty or resistance.

5 marks: Offers a developed analysis showing both sides: how exchanges strengthened loyalty (e.g., shared rights of Englishmen, common Protestant culture) and how they fostered resistance (e.g., colonial assemblies defending autonomy, exposure to political critiques).

6 marks: Provides a well-supported, analytical response that integrates specific evidence (e.g., representative assemblies, print culture, Atlantic communication networks) and clearly explains how the same exchanges could simultaneously promote unity with Britain and stimulate early resistance.