AP Syllabus focus:

‘New England, initially settled by Puritans, developed around small towns with family farms and built a thriving mixed economy of agriculture and commerce.’

New England’s early development reflected Puritan social ideals, family migration patterns, and adaptation to a challenging environment, producing small towns, cohesive communities, and a diversified regional economy.

Puritan Foundations of New England Society

New England’s distinctiveness began with the Puritan migration. Puritans were English Protestants who sought to reform the Church of England and build communities organized around their religious vision. Their migration patterns shaped the region’s demographic composition. Unlike the Chesapeake’s largely male, cash-seeking migrants, Puritan settlers typically arrived as families committed to creating stable, morally regulated towns built around shared spiritual goals.

Puritanism: A reform movement within English Protestantism that sought to purify the Church of England of remaining Catholic practices and emphasized moral discipline and covenant theology.

The Puritan commitment to community determined how land was distributed, how towns were organized, and how political authority functioned. The New England town became the central institution of governance and community life.

Exterior view of the Alna Meetinghouse in Maine, a late-18th-century example of the simple, wooden churches and meetinghouses that anchored many New England towns. Such buildings served simultaneously as religious and civic centers, reflecting the Puritan practice of fusing church life and town government. Although this structure dates slightly later than Period 2, its design and function closely resemble earlier colonial meetinghouses. Source.

Puritan Town Structure and Governance

Puritan towns developed in a patterned and intentional manner. Central to each settlement was the meetinghouse, a space used for both worship and civic deliberation. Surrounding this hub, small family farms were allocated in carefully measured plots. This structure enhanced communal oversight and ensured that social and religious norms remained central to daily life.

Town Meetings and Local Autonomy

The town meeting, a form of direct democratic governance, allowed male church members or freeholders to vote on local matters. This system fostered political participation and a sense of collective responsibility that distinguished New England from more oligarchic southern colonies.

Key characteristics included:

Annual elections for selectmen who carried out administrative duties

Collective decision-making on taxation, land distribution, and public works

Strong emphasis on moral regulation and enforcement of community standards

Although deeply participatory, political power still rested on religious membership and patriarchal norms, revealing both democratic tendencies and social exclusivity.

Environmental Conditions and the Rise of a Mixed Economy

New England’s environmental conditions shaped its economic trajectory. The region had rocky soil, a cooler climate, and shorter growing seasons than the southern colonies. As a result, large-scale plantation agriculture was impossible. Instead, settlers relied on family farms, typically producing diversified crops for household use and limited local trade.

Agricultural Practices

New England agriculture was characterized by:

Small, labor-intensive farms maintained by family units

Crops such as corn, rye, and squash grown primarily for subsistence

Limited surpluses that circulated through local or regional markets

The modest scale of agriculture reinforced community cohesion, interdependence, and tight settlement patterns.

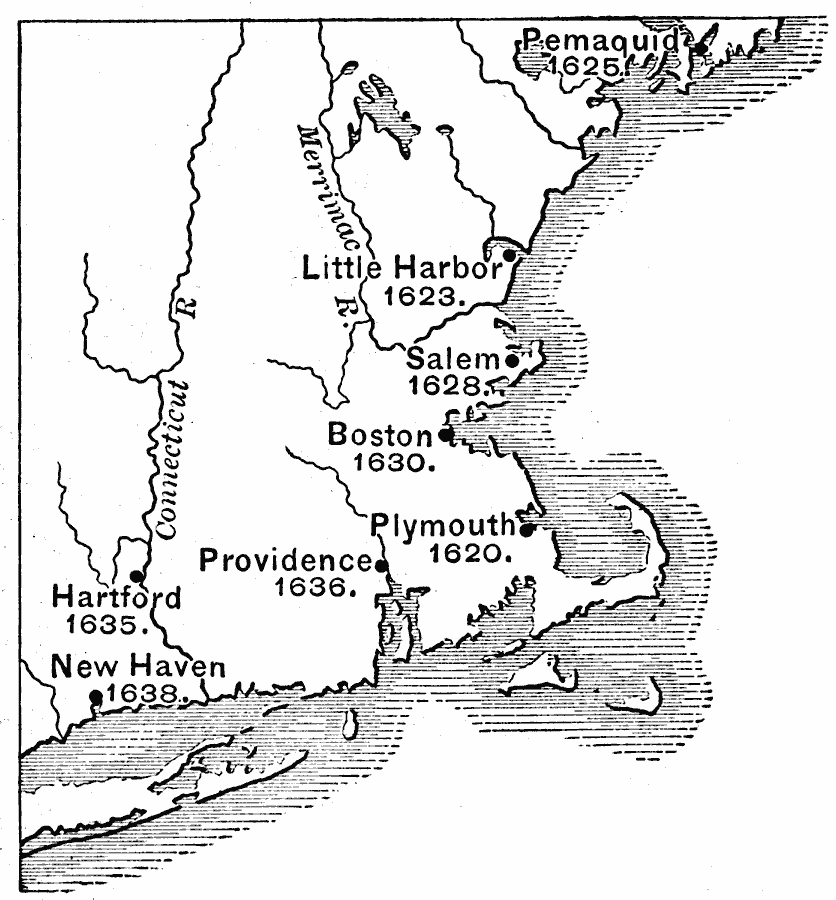

Settlements clustered near the coast and along navigable rivers, giving towns access to both local hinterlands and Atlantic shipping lanes.

Map of the New England colonies between 1620 and 1638 showing early permanent English settlements such as Plymouth, Salem, Boston, Providence, Hartford, and New Haven. The concentration of towns along the coast and major rivers illustrates how environment channeled New England’s development into compact communities tied to Atlantic trade. The map predates the full flowering of the mixed economy but accurately depicts the spatial foundations of Puritan town life. Source.

Commercial Development and Maritime Expansion

Despite an agrarian foundation, New England became a center of commerce and maritime enterprise.

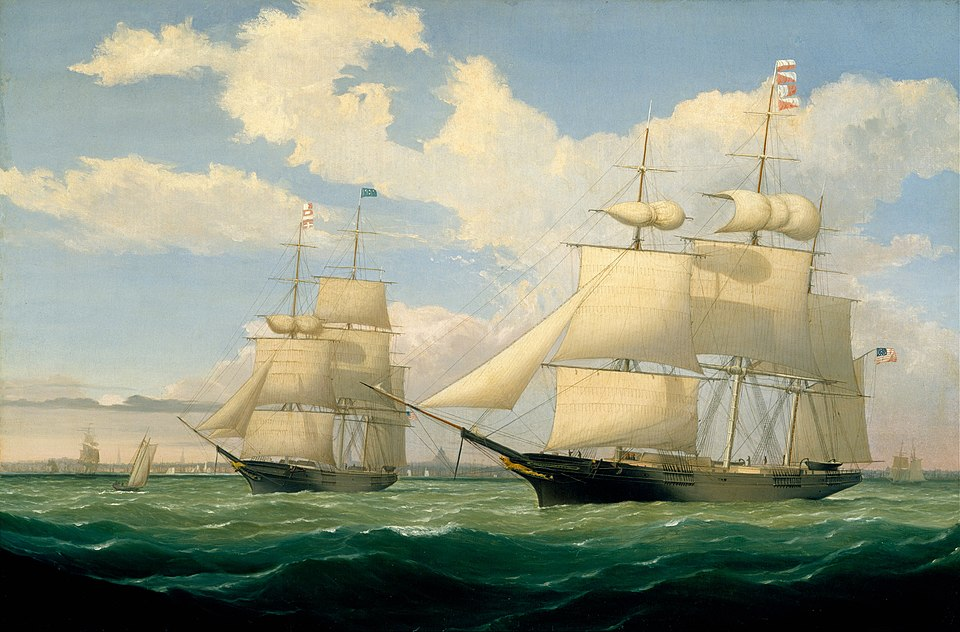

Fitz Henry Lane’s mid-19th-century painting of Boston Harbor shows large sailing ships, smaller craft, and a bustling waterfront, emphasizing shipping’s central role in New England’s economy. Although painted after the colonial era, the scene reflects economic patterns that began in the 17th and 18th centuries, when New England towns turned to shipbuilding, fishing, and trade alongside family farming. The image includes more vessels and a later harbor setting than strictly required by the syllabus, but it effectively illustrates the commercial side of New England’s mixed economy. Source.

Access to harbors, forests, and abundant fishing grounds supported a robust mixed economy rooted in trade, shipbuilding, and coastal resource extraction.

Key Components of the Mixed Economy

Fishing and whaling became profitable exports, especially cod

Shipbuilding, supported by vast timber resources, linked New England to transatlantic commerce

Artisan and merchant activity flourished in port towns such as Boston and Salem

Coastal and Atlantic trade connected New England to the Caribbean, supplying goods such as lumber, fish, and livestock in exchange for sugar and molasses

This evolving commercial network integrated the region into wider Atlantic systems while supporting growing social complexity.

Labor Systems and Social Structure

New England’s labor system differed from plantation colonies. Because farms were small and diversified, labor needs were met primarily by family members. Indentured servants were present but in smaller numbers than in the Chesapeake, and enslaved Africans formed only a small minority in the 17th century due to limited demand for plantation-style labor.

New England’s social order reflected Puritan values. Households were patriarchal, and social rank correlated with church standing, landholding, and moral reputation. While the region displayed higher literacy rates and a strong educational culture—both rooted in Puritan emphasis on Bible reading—it also enforced conformity through laws regulating behavior, dress, and public conduct.

Interactions with Native Peoples

New England’s settlement patterns affected relations with Indigenous groups. Town expansion, fencing of land, and the spread of livestock disrupted Native agriculture and hunting. Initially reliant on trade and diplomatic ties, the region increasingly experienced tension as English towns grew denser and demanded more land.

Notable developments included:

Increased English settlement leading to competition over fields and resources

Cultural and religious pressure exerted on Indigenous communities

Occasional trade partnerships coupled with rising mistrust

These dynamics foreshadowed major conflicts in the later 17th century, including Pequot resistance and the escalation toward King Philip’s War.

Long-Term Significance of New England’s Development

The Puritan commitment to organized towns, moral governance, and community participation created a foundation for broader colonial political culture. New England’s mixed economy—rooted in both agriculture and commerce—enabled resilience, upward mobility for some families, and the emergence of influential port cities that later played major roles in colonial resistance to British imperial policies.

This regional pattern, grounded in Puritan migration and shaped by environmental realities, produced one of the most distinctive social and economic systems in early British America.

FAQ

Puritan expectations encouraged constant moral self-regulation. Community members monitored one another for signs of proper behaviour, reinforcing a culture of social conformity.

Daily life centred on religious observance; activities such as Sabbath keeping, family prayers, and attendance at sermons structured the weekly rhythm of town life.

Households were expected to uphold discipline and order, reflecting the belief that strong families produced a stable godly community.

Puritans valued literacy because individuals were expected to read scripture independently. This produced exceptionally high literacy rates compared to other colonies.

As a result, New England invested early in grammar schools, apprenticeships, and local instruction, laying foundations for later colleges such as Harvard.

The emphasis on education contributed to a skilled labour force capable of supporting commerce, record keeping, and expanding maritime industries.

Population increase created pressure for additional farmland. Since Puritan family farms were small, younger generations needed new land to maintain independence.

Town charters were granted when groups petitioned colonial governments, often after exploring interior land or coastal sites.

Expansion followed a pattern: surveying land, allocating house lots and fields, constructing a meetinghouse, and establishing roads and common land.

Although towns promoted community unity, status distinctions remained clear. Wealthier landowners, merchants, and ministers held significant influence.

Access to leadership positions in town meetings often depended on property ownership and church membership, creating an elite core of decision-makers.

Poorer families, labourers, and servants participated less in governance and occupied peripheral economic roles.

Many inland towns produced goods for export through coastal hubs. These included timber, livestock, barrel staves, potash, and small agricultural surpluses.

Merchants in port towns organised trade routes to the Caribbean and Europe, transporting inland products while importing sugar, molasses, and manufactured goods.

Roads and river systems enabled regular movement of goods, tying rural producers to international markets despite the region’s modest agricultural base.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which Puritan beliefs influenced the development of towns in seventeenth-century New England.

Question 1

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a valid influence of Puritan beliefs (e.g., emphasis on community, moral order, or religious cohesion).

1 additional mark for explaining how this belief shaped a specific feature of town development (e.g., creation of central meetinghouses, collective land distribution, or close-knit settlement patterns).

1 additional mark for using specific and accurate historical detail (e.g., requirement for church membership, town meetings reflecting Puritan emphasis on moral governance).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse the extent to which environmental conditions shaped the mixed economy of New England in the seventeenth century. Use specific historical evidence to support your answer.

Question 2

Award up to 6 marks:

1–2 marks for describing relevant environmental conditions in New England (e.g., rocky soil, short growing seasons, extensive forests, coastal access).

1–2 marks for explaining how these conditions helped shape the mixed economy (e.g., subsistence-focused family farms, development of shipbuilding due to timber, maritime commerce encouraged by natural harbours).

1–2 marks for supporting the explanation with accurate, specific evidence (e.g., examples of port towns, references to fishing and coastal trade, contrast with plantation agriculture).

To reach the top of the band, the answer should form a coherent argument analysing the extent of environmental influence rather than merely listing factors.