AP Syllabus focus:

‘The Chesapeake and North Carolina grew prosperous exporting tobacco, first using mostly male indentured servants and later relying heavily on enslaved Africans for labor.’

Chesapeake and North Carolina societies transformed around tobacco cultivation, shaping economic growth, labor structures, settlement patterns, and racial hierarchy as shifting labor systems responded to demographic pressures and expanding plantation agriculture.

Chesapeake and North Carolina Tobacco Economies

Tobacco dominated the Chesapeake (Virginia and Maryland) and North Carolina, becoming the central export that tied these colonies to Atlantic markets. As a labor-intensive crop requiring year-round maintenance, tobacco shaped nearly every aspect of regional development. The strong European demand for tobacco encouraged constant expansion of plantation acreage, settlement along navigable rivers, and increasingly hierarchical societies organized around landownership and labor control.

Tobacco’s profitability meant that planters devoted the vast majority of their land to its cultivation, creating a monoculture economy dependent on reliable labor.

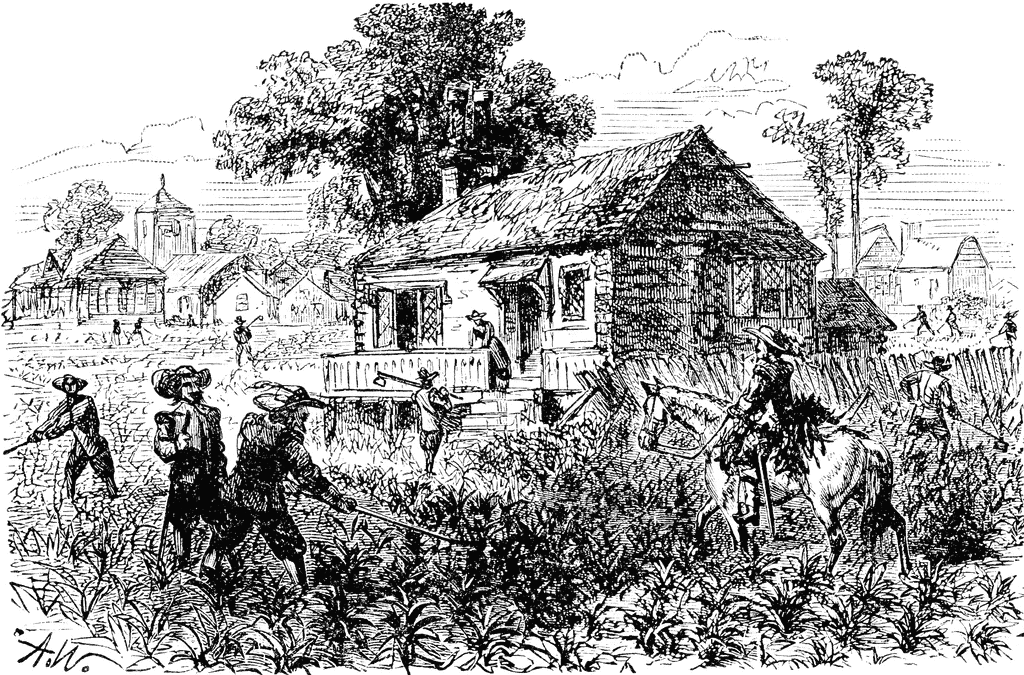

This illustration depicts tobacco harvesting in the Virginia colony, showing workers managing plants and leaves around plantation structures. It visually reinforces the labor-intensive nature of tobacco cultivation. Additional architectural details help contextualize the physical layout of early tobacco plantations. Source.

Because tobacco quickly exhausted soil nutrients, planters frequently sought new land, pushing settlement westward and intensifying conflicts with Indigenous peoples. The geography of the region—fertile soil, long growing seasons, and abundant waterways—allowed plantations to ship tobacco barrels directly to the Atlantic, linking local production to British mercantile networks.

This relief map shows Jamestown’s position on the James River within the Chesapeake region, illustrating how waterways enabled efficient export of tobacco. Modern political labels appear but help orient the location in contemporary geography. Source.

Indentured Servitude and Early Labor Structures

Predominance of Indentured Servants

During the first half of the 17th century, indentured servants formed the primary labor force. These laborers, mostly English men in their teens or twenties, exchanged several years of labor for passage, food, and eventual “freedom dues.”

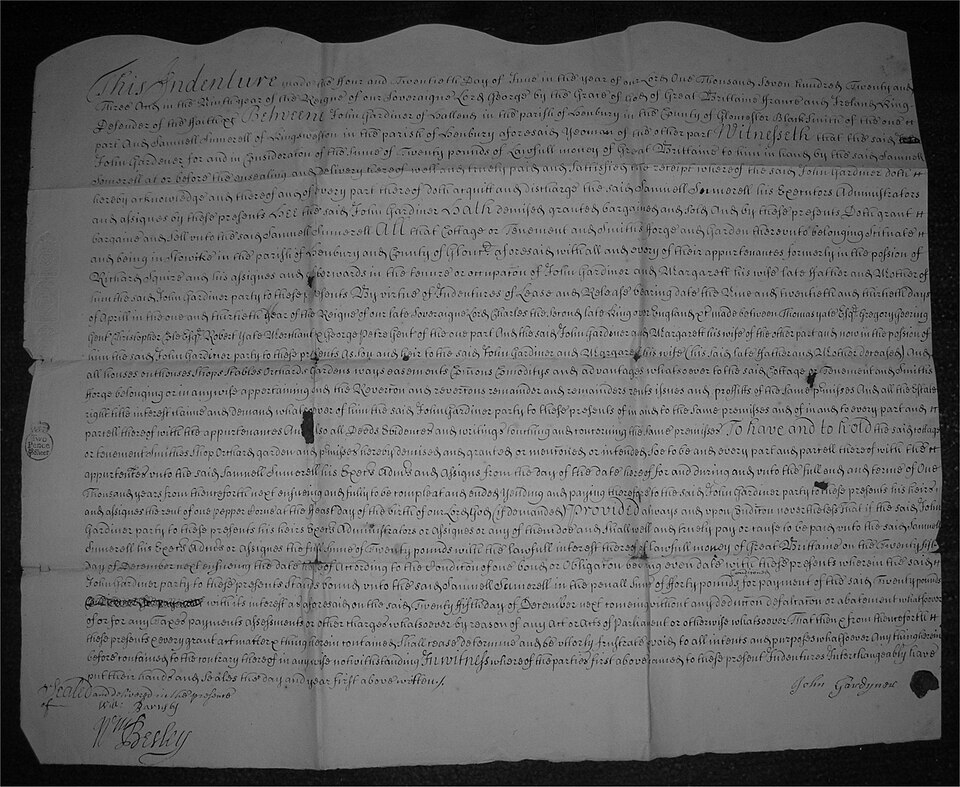

This manuscript page shows a formal indenture contract from 1723, illustrating the legal structure that bound servants to fixed terms of labor. Its detailed language reflects the contractual nature of early Chesapeake labor systems. Source.

Indentured Servant: A worker bound by a labor contract for a fixed term in exchange for passage or other compensation.

Planters preferred indentured servants because they were initially cheaper than enslaved Africans and more readily available in England’s struggling economy. Labor contracts gave masters substantial authority, including the ability to extend service for rule violations. Completion of an indenture theoretically allowed former servants to seek land and economic independence, though diminishing land availability limited that promise over time.

One important pattern shaped regional society: the overwhelming arrival of men created skewed sex ratios, slowing family formation and fostering high population mobility in the Chesapeake and North Carolina during the early decades.

Decline of Indentured Labor

By the late 1600s, several factors reduced the availability and desirability of indentured servants:

Improving English economic conditions, making migration less attractive.

Rising colonial demand for permanent, controllable labor.

Social instability linked to landless former servants, illustrated by uprisings such as Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676.

These pressures encouraged the shift toward racially based chattel slavery, which offered planters lifetime labor and inheritable status.

Expansion of African Slavery

Establishment of a Racialized Labor System

From the late 17th century onward, enslaved Africans became the foundation of the tobacco labor system. Planters purchased enslaved laborers through the Atlantic slave trade, integrating the Chesapeake and North Carolina more deeply into transatlantic economic networks. The transition was gradual but decisive, driven by the long-term economic advantages of lifetime servitude.

Chattel Slavery: A system in which individuals are legally property, inheriting enslaved status through their mothers and possessing no recognized personal freedom.

Enslaved Africans brought agricultural knowledge, cultural traditions, and social networks that shaped plantation life. Though smaller in scale than the massive sugar plantations of the Caribbean, tobacco plantations required constant labor for planting, weeding, harvesting, and curing, ensuring year-round exploitation of enslaved workers.

Regional Variations

While the Chesapeake developed larger plantations with growing enslaved populations, North Carolina maintained a mix of small farms and modest plantations. Its swampy terrain and initially weaker commercial infrastructure slowed the development of large-scale slavery, but enslaved labor nonetheless became increasingly central to its tobacco and naval stores industries.

Social and Political Impacts of Labor Systems

Emergence of a Hierarchical Society

The transition from indentured servitude to slavery reshaped social patterns:

A planter elite accumulated wealth, political power, and vast landholdings.

Small farmers occupied the middle tiers of society.

Enslaved Africans formed the coerced labor base at the bottom of the hierarchy.

This structure encouraged laws that hardened racial distinctions, restricted mobility, and created long-lasting social divisions.

Political Power and Plantation Governance

The planter class dominated colonial legislatures such as the House of Burgesses in Virginia. Their political influence protected landownership, expanded slavery through legal codification, and ensured favorable economic policies. As plantations grew, these elites shaped the religious and cultural character of the region, prioritizing stability and labor control over communal institutions common in other colonial regions.

Cultural Life under Forced Labor

Enslaved Africans developed systems of resistance—including work slowdowns, covert sabotage, and the preservation of kinship and spiritual traditions—to survive dehumanizing conditions. Meanwhile, tobacco planters focused on reinforcing racial hierarchy to justify the expanding system.

Economic and Environmental Legacy

Tobacco wealth fostered demographic growth, rising exports, and stronger ties to British markets. Yet soil depletion and dependence on a single crop made the region vulnerable to fluctuations in European demand. The long growing season and reliance on enslaved labor ensured that the Chesapeake and North Carolina remained tied to plantation agriculture throughout the colonial era.

FAQ

Planters relied on simple but specialised tools such as hoes, wooden dibbles for planting, and hand-operated curing frameworks. These tools required dexterity more than capital investment.

Tobacco was cured in ventilated barns where controlled heat slowly dried the leaves. Variations in airflow and smoke contributed to quality differences.

Labourers performed repetitive processes including topping plants, trimming leaves, and hand-rolling tobacco bundles. Skill in these steps directly affected market value.

Large planters amassed riverfront estates because deep water access allowed ships to load tobacco directly, eliminating the need for major port towns.

Small farmers tended to settle inland on less fertile soil, producing lower yields and fewer exportable crops.

This division created a spatial hierarchy:

• riverfront elite

• middling inland farmers

• landless labourers and enslaved workers

The region’s swampy environment encouraged diseases such as malaria and dysentery, which killed many newcomers within their first years.

High early mortality reduced the long-term value of enslaved labour, making indentured servitude more appealing for planters until the late seventeenth century.

As population stability improved, slave ownership became economically advantageous because enslaved workers provided lifetime labour and hereditary status.

Colonial governments introduced inspection warehouses where officials graded tobacco before export. Grading aimed to protect quality and maintain favourable British demand.

Certificates issued by inspectors functioned almost like currency, enabling planters to use tobacco credits to settle debts.

The system:

• raised product consistency

• strengthened ties to British merchants

• encouraged standardisation across plantations

Parishes often acted as administrative units that collected taxes, maintained roads, and provided poor relief, giving them a civil role beyond religious duties.

Because elite planters dominated parish vestries, they used these bodies to reinforce social hierarchy and local governance.

This influence helped stabilise plantation society by regulating behaviour, supporting order, and maintaining social expectations across dispersed rural communities.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why tobacco cultivation shaped the development of the Chesapeake colonies in the seventeenth century.

Question 1

• 1 mark: Identifies a valid reason (e.g., tobacco’s profitability, high European demand, labour-intensive nature).

• 2 marks: Provides a simple explanation of how this reason shaped development (e.g., encouraged expansion of plantation agriculture or increased reliance on bound labour).

• 3 marks: Offers a developed explanation showing clear links between tobacco cultivation and colonial settlement patterns, economic structures, or labour demands.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how changes in labour systems from indentured servitude to African chattel slavery affected social and economic structures in the Chesapeake and North Carolina.

Question 2

• 4 marks: Describes relevant changes in labour systems, outlining the move from indentured servitude to racialised African slavery, with some accurate factual detail.

• 5 marks: Explains how these changes affected both social hierarchy and economic organisation, referencing planters, small farmers, and enslaved Africans.

• 6 marks: Provides a well-developed analysis with specific evidence (e.g., shifting demographics, planter dominance, slave laws, plantation expansion), clearly linking labour changes to broader regional development.