AP Syllabus focus:

‘The spread of European Enlightenment ideas, along with newspapers and other print networks, connected colonists to Atlantic debates and encouraged shared political and cultural attitudes.’

Transatlantic connections accelerated the flow of Enlightenment ideas, enabling British American colonists to participate in shared debates on politics, religion, science, and society as print culture expanded dramatically.

Enlightenment Thought Reaches British North America

The Enlightenment—an 18th-century intellectual movement emphasizing reason, natural laws, and human improvement—profoundly shaped colonial culture and politics.

Enlightenment: An intellectual movement stressing reason, empirical inquiry, individual rights, and the use of science to understand and improve society.

As the Atlantic world became increasingly interconnected, colonists encountered new philosophical writings through imported books, letters, periodicals, and scientific correspondence. These ideas promoted a worldview that challenged traditional authority and encouraged colonists to evaluate government, religion, and society through the lens of reason. Influential European thinkers such as John Locke, Montesquieu, and Voltaire argued for concepts that resonated in the colonies, including natural rights, social contracts, separation of powers, and religious toleration.

Key Enlightenment Themes Influencing Colonial Thought

Natural rights encouraged colonists to see liberties as inherent rather than granted by monarchs.

Republicanism emphasized civic virtue, the public good, and vigilance against corruption.

Skepticism toward arbitrary authority inspired critiques of imperial power and religious orthodoxy.

Scientific inquiry stimulated interest in education, experimentation, and the classification of the natural world.

These themes circulated widely due to an expanding colonial intellectual infrastructure.

Expansion of a Transatlantic Print Culture

Print culture grew rapidly in the British colonies during the 18th century, providing the primary medium through which Enlightenment ideas entered daily life. The increase in literacy, especially in New England, created a receptive audience for publications.

Growth of Printing Presses and Local Publications

By the early 1700s, printing presses operated in major towns such as Boston, Philadelphia, and New York.

A reconstructed eighteenth-century printing press illustrates the technology used in colonial print shops. Such presses produced newspapers and pamphlets that transmitted Enlightenment ideas across the Atlantic world. Museum display elements appear in the image, providing historical context beyond the syllabus. Source.

Printers produced newspapers, pamphlets, sermons, almanacs, and political essays that blended local concerns with European ideas.

Newspapers multiplied across the colonies, fostering a shared informational environment.

Pamphlets offered brief, accessible discussions of political and philosophical issues.

Almanacs, including the famous works of Benjamin Franklin, blended practical information with Enlightenment-inspired reflections on human behavior, virtue, and industry.

Print culture: The shared set of ideas, debates, and information circulated through printed materials such as newspapers, pamphlets, and books.

Through these publications, colonists increasingly engaged with topics far beyond their immediate surroundings.

Atlantic Networks and Intellectual Exchange

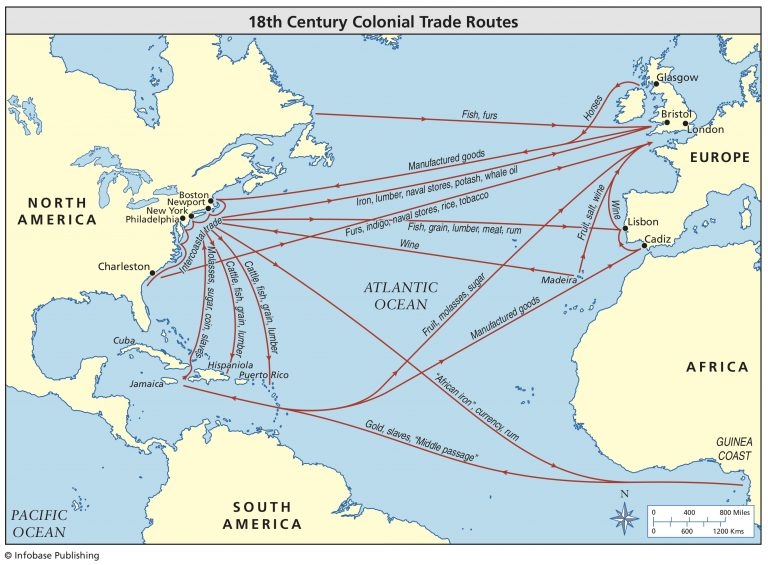

The flow of ideas across the Atlantic was supported by robust commercial and social connections linking Britain, Europe, Africa, the Caribbean, and North America. Ships carried not only goods but also correspondence, books, and printed debates.

This eighteenth-century trade map shows major Atlantic shipping routes connecting British American ports with the Caribbean, Africa, and Great Britain. Although focused on commodity flows, these same routes carried letters, newspapers, and pamphlets essential to transatlantic print culture. Some economic details exceed syllabus needs but reinforce how intellectual and commercial networks overlapped. Source.

Mechanisms of Transmission

Merchants and travelers transported texts and news between colonial ports and Europe.

Learned societies, including libraries and philosophical associations, encouraged reading and discussion of Enlightenment writings.

Postal routes improved communication among colonies and between the colonies and Britain.

Reprinted texts allowed controversial or influential essays from London to reach colonial readers quickly and cheaply.

Through these mechanisms, colonists encountered and contributed to conversations about politics, science, economics, and religion that extended across the Atlantic world.

Colonial Participation in Atlantic Debates

Colonists did not merely consume Enlightenment ideas—they adapted them to their specific circumstances. British American writers engaged with topics such as governance, commerce, and religious toleration, relating them to local issues such as colonial assemblies, frontier conflicts, and religious pluralism.

Contributions from Colonial Intellectuals

Benjamin Franklin exemplified Enlightenment engagement through his scientific work, civic involvement, and prolific publishing.

This painting depicts Benjamin Franklin at work in his print shop, highlighting his dual role as printer and Enlightenment thinker. Franklin’s publications helped spread ideas about reason, virtue, and civic life throughout the colonies. Additional workshop details appear but serve to contextualize an eighteenth-century printing environment. Source.

James Otis, John Dickinson, and other political writers drew upon Enlightenment principles to critique imperial policies.

Clergy influenced by Enlightenment reasoning promoted more rational forms of religious thought, helping to reshape Protestant traditions.

Colonial thinkers thus became active participants in shaping the political and cultural direction of the empire.

Effects on Political and Cultural Attitudes

As print networks broadened, colonists developed increasingly shared attitudes about governance, identity, and rights. This growing intellectual cohesion helped unify diverse colonial regions.

Political Consequences

Frequent discussion of rights and constitutionalism encouraged colonists to expect a greater voice in governance.

Shared critiques of corruption and tyranny helped establish a political vocabulary later used during resistance to imperial control.

Ideas about limited government and popular sovereignty gained legitimacy through repeated circulation in newspapers and pamphlets.

Cultural and Social Effects

Print culture fostered a public sphere—an informal space where individuals debated issues of common concern.

Increased access to books and newspapers promoted literacy and self-improvement.

The blending of European ideas with colonial experiences produced a distinctively British American intellectual tradition.

FAQ

Colonial newspapers tended to condense or adapt British essays, making Enlightenment concepts more accessible to readers with limited formal education. They also reprinted political arguments more freely due to looser enforcement of press restrictions.

Unlike many London papers shaped by intense party politics, colonial newspapers often emphasised moral improvement, civic participation, and local implications of Enlightenment debates.

Almanacs reached a far broader audience than most printed works because they were inexpensive and practical, ensuring annual mass readership.

Writers embedded Enlightenment themes subtly in proverbs, humour, and reflections on human behaviour, allowing readers to encounter rationalist ideas without reading formal philosophy.

Bookshops imported European texts and sold pamphlets, newspapers, and scientific treatises, making Enlightenment writings physically accessible.

Circulating libraries expanded access by lending books to customers who could not afford to buy them outright, encouraging shared reading, discussion, and the emergence of local intellectual communities.

Urban artisans, merchants, clergy, and educated farmers found greater access to political and scientific information that supported social mobility and civic engagement.

Women in urban areas also benefited through increased literacy and access to newspapers and sermons, allowing participation in household-level intellectual debate even when excluded from formal politics.

Enhanced postal routes reduced the time required for letters, newspapers, and books to travel between colonies and across the Atlantic.

This speed made intellectual exchange more dynamic by enabling:

Faster reprinting of British essays.

More regular correspondence between colonial and European thinkers.

Wider dissemination of scientific discoveries, political arguments, and cultural trends.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which Enlightenment ideas influenced political thought in the British North American colonies during the eighteenth century.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks for a valid explanation that clearly links Enlightenment ideas to colonial political thought.

1 mark for identifying an Enlightenment idea (e.g., natural rights, social contract, separation of powers, rational critique of authority).

1 mark for describing how this idea appeared in colonial discourse (e.g., in pamphlets, sermons, or political debates).

1 mark for explaining the influence on colonial thinking (e.g., encouraging demands for greater self-government, scepticism toward arbitrary imperial authority).

Answers that simply list Enlightenment thinkers without explanation should receive a maximum of 1 mark.

(4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of the period 1607–1754, analyse how the growth of a transatlantic print culture contributed to the spread of shared political and cultural attitudes among the British colonies.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award marks based on the extent to which the response provides a historically accurate, analytical explanation supported by relevant evidence.

1–2 marks: General statements about print or communication with little specific explanation of colonial change. Limited or no use of evidence.

3–4 marks: Shows understanding of transatlantic print culture and gives some explanation of its impact, with at least one piece of relevant evidence (e.g., newspapers, pamphlets, circulation of British texts, Franklin’s publications).

5–6 marks: Offers a well-developed analysis explaining how print networks fostered shared political and cultural attitudes. Uses multiple specific examples (e.g., growth of colonial newspapers, reprinting of British political essays, exchange of Enlightenment texts). Clearly links print culture to broader ideological developments such as emerging critiques of British authority, increased literacy, and participation in Atlantic debates.

High-scoring answers must explicitly connect print culture to the spread of shared attitudes, not simply describe Enlightenment ideas in isolation.