AP Syllabus focus:

‘Diverging interests led to mistrust between colonists and British leaders; colonists criticized imperial policies over defense, settlements, self-rule, and trade and drew on ideas of liberty and local self-government.’

Growing tensions between Britain and its North American colonies emerged from disputes over authority, trade restrictions, security responsibilities, and evolving colonial expectations for political participation and individual liberty.

Rising Mistrust and Diverging Interests

As Britain expanded imperial oversight after periods of salutary neglect—loose enforcement of trade and governance rules—colonists increasingly viewed imperial actions as intrusive. Britain believed stronger direction was necessary to secure its empire and finance defense, while colonists expected continued autonomy. These contrasting objectives fostered widespread suspicion, particularly as British policymakers questioned colonial loyalty and competence. Colonists, in turn, feared that expanded imperial control threatened their accustomed rights as British subjects and their local political traditions.

This map depicts the Thirteen British Colonies in North America around 1775, visualizing the territorial setting of debates over taxation, representation, and imperial authority. It highlights key coastal regions where political tensions intensified. The image focuses on colonial boundaries without adding major details beyond geographic context. Source.

Imperial Defense and Colonial Responsibilities

After mid-17th-century conflicts and later imperial wars, British officials insisted that colonies contribute more actively to imperial defense, including frontier fortifications and troop provisions. Colonists often resisted these demands because they viewed standing armies as threats to liberty and because provincial assemblies believed they alone possessed legitimate authority to levy taxes.

British authorities argued that defense burdens were shared imperial obligations.

Colonial assemblies insisted that defense decisions should follow local control and local taxation.

Disputes intensified as governors sought compliance while assemblies withheld funds or attached political conditions to appropriations.

Settlement Policies and Land Tensions

Britain’s efforts to regulate westward settlement deepened conflict. Policies designed to stabilize relations with Native nations, control speculative land claims, and prevent costly frontier wars were perceived by colonists as violations of economic opportunity and self-direction.

Restrictions on settlement threatened colonial expectations for landownership as a foundation for prosperity and political independence.

Colonists often accused Britain of prioritizing imperial revenue and diplomacy over the needs of frontier communities.

British officials interpreted colonial defiance as proof that assemblies could not responsibly manage territorial expansion.

These disputes over land reinforced broader concerns that imperial authority sought to curtail colonial development for Britain’s benefit.

This map illustrates the Proclamation Line of 1763 and the later Indian Boundary Line of 1768, demonstrating British attempts to restrict westward settlement. These boundaries help explain colonial frustration with imperial land policy. The map includes additional context such as Native territories, which goes slightly beyond syllabus requirements but supports understanding of frontier constraints. Source.

Self-Rule and Colonial Political Identity

Colonists had long practiced local self-government, which referred to community-based political decision-making through town meetings, elected assemblies, and representative institutions. Assemblies controlled taxation, expenditures, militia organization, and many internal regulations. When Britain attempted to standardize administration or limit assembly prerogatives, colonists saw such measures as direct assaults on local autonomy.

Self-rule: The practice of local political authority exercised by colonial assemblies and town meetings, rooted in English traditions of representative governance.

Colonists repeatedly invoked the rights of Englishmen, asserting that legitimate government required consent of the governed, especially in taxation. British leaders countered that Parliament held supreme authority throughout the empire, whether or not colonists elected representatives to it. This fundamental constitutional disagreement magnified every policy dispute.

Regular interactions within assemblies reinforced political habits rooted in debate, public petitioning, and communal accountability.

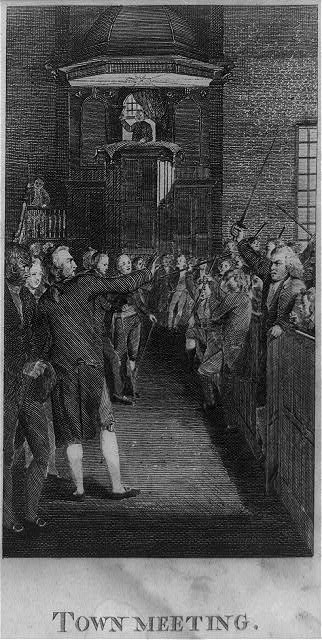

This engraving portrays a heated colonial town meeting, illustrating how assemblies cultivated habits of open debate and collective decision-making. Such settings nurtured political expectations for self-rule and resistance to arbitrary authority. Architectural and clothing details reflect the era without adding content beyond what supports understanding of early political culture. Source.

Trade Regulation and Mercantilist Policies

Tensions escalated through disputes over trade. Britain pursued mercantilist regulation to channel colonial commerce toward imperial benefit. Laws governing shipping, customs duties, and commodity flows aimed to ensure that wealth circulated within the empire. For decades, these acts were poorly enforced, enabling colonial merchants to build networks that operated with significant independence.

When Britain intensified enforcement—tightening customs inspections, curbing smuggling, and increasing prosecutorial oversight—colonists interpreted the shift as evidence that Britain sought economic domination rather than mutual prosperity.

Merchants protested that new restrictions threatened commercial flexibility.

Planters feared reduced access to markets or credit.

Urban workers criticized disruptions to maritime trade.

These responses reflected shared anxieties that imperial control undermined local economic stability.

Conceptualizing Liberty in the Imperial Crisis

As conflicts multiplied, colonists increasingly linked grievances to broader ideas of liberty, drawing upon Enlightenment political thought, English constitutional traditions, and Protestant moral arguments. Liberty was not merely an abstract ideal; colonists associated it with property rights, consent-based government, and resistance to corruption or arbitrary rule. Many argued that self-governing practices cultivated public virtue and protected communities from tyranny.

Liberty: A political condition in which individuals and communities are protected from arbitrary authority, grounded in rights to property, representation, and legal due process.

The belief that Britain endangered these principles transformed policy disagreements into ideological conflict. Newspapers, sermons, and pamphlets amplified the idea that defending liberty required vigilance and collective action. Although colonists still professed loyalty to the crown, they increasingly viewed British policies as incompatible with the political freedoms they understood as foundational to their society.

The Growth of Colonial Resistance

By the early 18th century, resistance took varied forms: formal petitions, non-importation agreements, and public protests. Assemblies cited constitutional arguments; merchants mobilized economic pressure; and ordinary colonists expressed grievances through civic participation.

Political leaders stressed that unchecked imperial control threatened all colonial rights.

Local committees coordinated responses across regions.

Public discourse framed resistance as a defense of inherited liberties rather than rebellion.

These developments strengthened intercolonial communication and fostered shared political attitudes. The convergence of disputes over defense, land, self-government, trade, and liberty created lasting mistrust, setting the stage for future conflicts as colonists increasingly questioned the legitimacy of British authority.

FAQ

Newspapers circulated political ideas rapidly, allowing colonists to share concerns about imperial power beyond local communities.

They often reprinted critical essays from Britain, which helped colonists recognise that debates over liberty and constitutional limits were part of a wider imperial conversation.

Editors also framed British policies as potential threats to colonial rights, influencing public opinion and encouraging vigilance against perceived abuses.

In British political culture, standing armies were traditionally associated with monarchical overreach, corruption, and suppression of civil freedoms.

Colonists feared that regular troops could enforce unpopular laws or bypass elected assemblies.

This suspicion grew stronger when troops were quartered near coastal towns, heightening concerns that Britain intended to assert military rather than constitutional authority.

Merchants relied on flexible Atlantic networks that included smuggling, credit arrangements, and informal exchange patterns.

Tighter customs enforcement threatened profits and increased operational risk, prompting traders to oppose imperial policies not only on ideological grounds but also to preserve commercial autonomy.

Urban labourers, shipbuilders, and dockworkers also worried about job stability if maritime activity became more restricted.

A growing number of colonial lawyers had studied English common law principles, including notions of due process and limits on arbitrary power.

These lawyers drafted petitions, resolutions, and pamphlets asserting that colonial assemblies possessed legitimate authority.

They also popularised constitutional ideas within towns, helping ordinary colonists connect daily grievances to broader debates about rights and governance.

Colonists argued that legitimate taxation required actual representation, meaning elected, local representatives directly accountable to their communities.

Britain defended the concept of virtual representation, claiming Parliament represented all subjects regardless of electoral participation.

This fundamental divide made compromise difficult, as colonists viewed the British model as dismissive of their political realities, while Britain saw colonial objections as challenges to imperial sovereignty.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify and briefly explain one reason why British attempts to increase imperial control in the early eighteenth century created mistrust among American colonists.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark

• Identifies a valid reason (e.g., stricter enforcement of trade laws, limits on westward settlement, interference with colonial assemblies).

2 marks

• Provides a brief explanation of how this action increased mistrust (e.g., colonists viewed restrictions as infringements on their traditional rights or economic freedoms).

3 marks

• Offers a clear explanation linking British policy to colonial perceptions of lost autonomy or threats to liberty.

(Example: Colonists believed increased imperial oversight violated established practices of self-government, generating suspicion of British intentions.)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how disputes over land, self-rule, and trade contributed to growing tensions between Britain and the American colonies in the period before 1754. Use specific historical evidence to support your answer.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks

• Describes at least two sources of tension (land, self-rule, trade) with basic factual accuracy.

• Provides some supporting evidence (e.g., restrictions on settlement, assertion of parliamentary supremacy, tightening of customs enforcement).

5 marks

• Explains how each factor contributed to worsening relations.

• Demonstrates clarity in linking British policies to colonial reactions, such as protests or claims to the rights of Englishmen.

6 marks

• Offers a well-organised and fully developed explanation addressing all three areas: land, self-rule, and trade.

• Integrates specific evidence (such as settlement restrictions that limited opportunity, assembly resistance, or enforcement of mercantilist regulations).

• Shows strong analytical linkage between imperial actions and colonial fears about threats to liberty and autonomy.