AP Syllabus focus:

‘Transatlantic exchanges tied colonists more closely to Britain and one another, yet British efforts to control trade and politics also sparked resentment and resistance to imperial authority.’

Transatlantic exchanges in commerce, culture, and politics increasingly bound Britain’s colonies together, yet Britain’s tightening imperial controls intensified colonial identity, heightened tensions, and fostered widespread resistance across regions.

Comparing Atlantic Exchanges: Identity, Trade, and Resistance

Transatlantic Trade Networks and Imperial Integration

By the early 18th century, expanding Atlantic trade networks linked Britain, its North American colonies, the Caribbean, and Africa into a dynamic web of exchange.

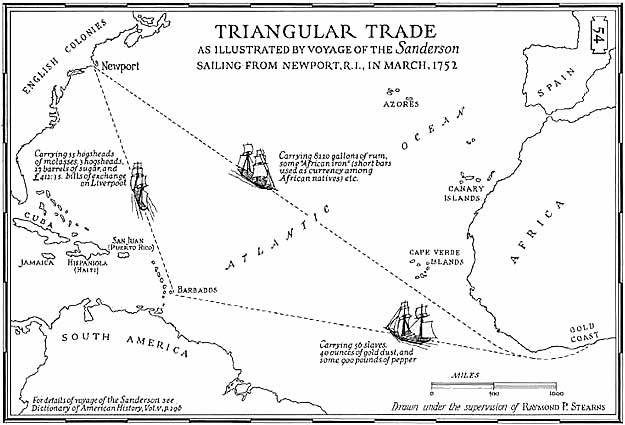

Map illustrating the triangular trade routes connecting New England, the Caribbean, and West Africa on the 1752 voyage of the ship Sanderson. Arrows trace the movement of manufactured goods, enslaved Africans, and colonial products across the Atlantic, demonstrating how commerce tied the colonies into a larger imperial system. The map includes specific ports and cargo notes not required by the syllabus, but these details provide one concrete example of the broader Atlantic trading pattern. Source.

These routes funneled raw materials, enslaved labor, and manufactured goods throughout the empire, reinforcing British economic priorities and socially connecting distant colonial societies.

• Colonists purchased British textiles, metal goods, books, and luxury items, demonstrating increasing participation in a shared British commercial culture.

• Colonial exports—especially tobacco, rice, indigo, lumber, and furs—integrated local economies into a broader imperial marketplace.

• Port cities such as Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston became vibrant hubs of maritime commerce and cosmopolitan cultural exchange.

The concept of mercantilism, introduced here as an important imperial strategy, shaped Britain’s efforts to manage trade.

Mercantilism: An economic system in which governments regulate trade to strengthen national power by maximizing exports and limiting imports.

Growing commercial interdependence strengthened colonists’ sense of belonging to the British Empire, even as it exposed them to increasing imperial intervention.

Cultural Exchange and the Growth of British American Identity

Transatlantic print culture, religious movements, and intellectual developments accelerated cultural convergence between Britain and its colonies.

• Newspapers circulated widely, connecting distant settlements and enabling colonists to follow debates in Parliament and across the empire.

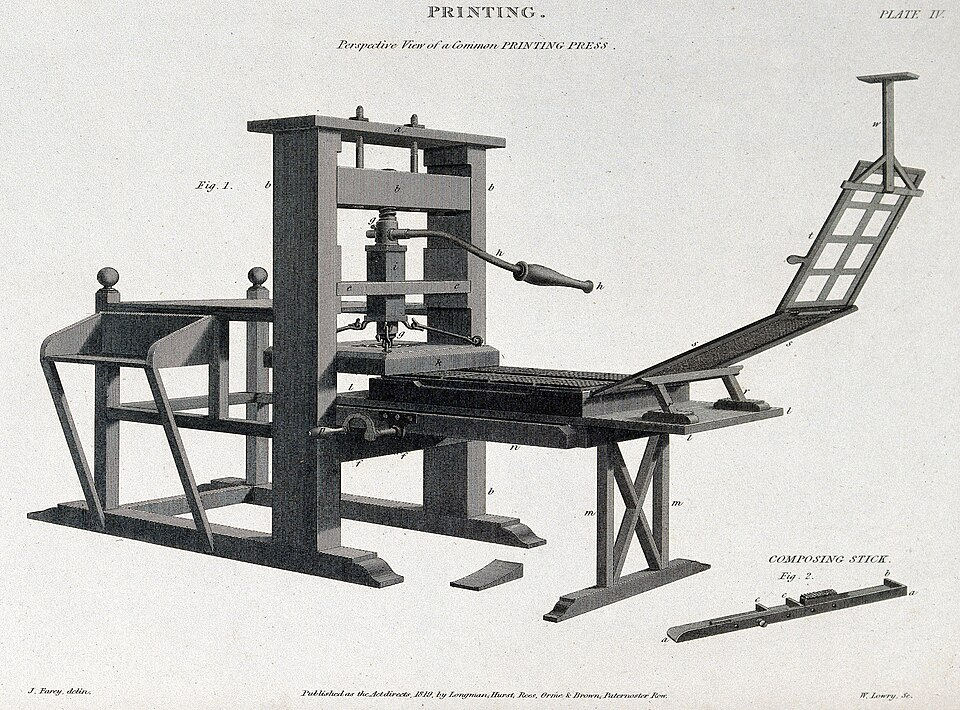

Engraving of an early 19th-century hand press, similar in design to presses used in the British colonies to print newspapers, pamphlets, and broadsides. The press shows the screw mechanism and platen used to transfer inked type to paper, enabling rapid reproduction of news and political commentary. Although this specific press dates from 1819, its structure closely matches eighteenth-century presses that powered transatlantic print culture and debate. Source.

• The transatlantic movement of ministers and religious tracts during evangelical revivals helped foster a shared Protestant framework.

• Enlightenment works by thinkers such as Locke and Montesquieu traveled along the same trade routes, encouraging colonists to engage in political discussions about natural rights, governance, and representation.

These exchanges nurtured a growing British American identity that blended loyalty to the crown with distinctive colonial experiences. This identity was not uniform; regional differences persisted, but shared cultural references increasingly linked colonists across the continent.

After this cultural expansion, shifts in imperial policies became more visible and controversial.

British Attempts at Imperial Control

As trade expanded, British leaders sought to convert economic ties into more structured political authority. Various commercial regulations aimed to keep colonial production aligned with imperial needs.

• The Navigation Acts restricted trade to English ships and required certain colonial goods to pass through English ports.

• Customs officials, vice-admiralty courts, and expanded bureaucratic supervision attempted to curb widespread smuggling and improve revenue collection.

• Imperial proposals—such as more centralized administration or new taxation schemes—reflected Britain’s desire to systematize its empire.

British policymakers believed these efforts would secure the empire’s prosperity and reduce conflict with European rivals. Colonists, however, perceived many of these measures as infringements on traditional practices of local self-government, a concept rooted in long-established colonial assemblies and town meetings.

Local Self-Government: A political tradition in which colonists exercised control over taxation and local laws through elected assemblies and town institutions.-

Differences in how British officials and colonists understood authority intensified strains within the Atlantic world.

Varied Colonial Reactions and Emerging Resistance

While economic ties fostered unity, colonial responses to British control varied by region and circumstance. Some colonists complied with imperial regulations when these aligned with local interests, especially merchants who profited from legal trade. Others circumvented restrictions through smuggling or forged partnerships with Caribbean or European traders outside official channels.

• In New England, where commerce dominated, strict enforcement threatened livelihoods and fueled opposition.

• In the Middle Colonies, diverse populations debated imperial involvement through an increasingly robust print culture.

• In the Southern colonies, planter elites resented interference with agricultural exports and feared disruptions to slave-based economies.

Resistance took multiple forms, ranging from public protest and petitioning to nonimportation agreements that boycotted British goods. These strategies revealed the growing ability of colonists to coordinate across regions—an unintended consequence of the very exchanges Britain had encouraged.

As colonists interacted more frequently through commerce, print, and shared grievances, they developed a stronger sense of collective political identity. This interconnected identity increasingly framed British imperial initiatives as threats not just to local interests but to broader notions of liberty and constitutional rights grounded in English political tradition.

Identity, Exchange, and the Roots of Resentment

Transatlantic exchanges forged both tighter bonds and deeper fractures within the British Empire. Enhanced trade and cultural interconnectedness strengthened imperial unity, yet they also gave colonists the tools—shared communication networks, political vocabulary, and coordinated action—to challenge British authority. By comparing these developments across regions, it becomes clear that the same Atlantic exchanges that integrated the colonies ultimately empowered resistance, setting the stage for escalating tensions in the decades ahead.

FAQ

Shared commercial interests and circulation of news fostered informal networks among merchants, printers, and political leaders across regions.

These networks made it easier for colonies to coordinate responses to trade disruptions or conflicts, as they already had channels for exchanging information and shared expectations about economic and political rights.

Colonial print culture was more decentralised, with numerous small presses producing regionally focused material tailored to local concerns.

Printers often reprinted British essays or parliamentary debates but added commentary reflecting American conditions, creating a hybrid discourse that blended imperial perspectives with colonial experiences.

Merchants relied on predictable transatlantic markets and shipping protections, so any increase in regulations, inspections, or customs fees directly affected profit margins.

They were often the first to detect shifts in imperial enforcement and sometimes led early resistance movements, including drafting petitions or organising boycotts.

Evangelical ministers moved between Britain and the colonies, spreading ideas about spiritual equality and moral accountability that could be applied to political authority.

These networks encouraged colonists to question hierarchical structures, including civil government, especially when imperial officials appeared to violate principles of justice or virtue.

Many colonists followed British debates about corruption, patronage, and the power of the executive through transatlantic newspapers and pamphlets.

Seeing similar trends in imperial administration, colonists feared that increased control threatened their own liberties, strengthening arguments that local self-government offered better protection against arbitrary rule.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one way in which transatlantic trade contributed to the development of a shared British American identity in the eighteenth century. Explain how this development strengthened connections within the empire.

Mark scheme

• Identification of a relevant aspect of transatlantic trade (1 mark)

Examples: circulation of British manufactured goods; spread of newspapers; movement of people and ideas across the Atlantic.

• Explanation of how this aspect contributed to a shared British American identity (1 mark)

• Explanation of how this development strengthened imperial connections (1 mark)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain two ways in which British attempts to tighten imperial control in the eighteenth century conflicted with the effects of transatlantic exchanges. Evaluate how these conflicts contributed to the growth of colonial resistance.

Mark scheme

• Identification of one relevant British imperial policy or initiative (1 mark)

Examples: Navigation Acts enforcement; expansion of customs officials; use of vice-admiralty courts.

• Explanation of how this policy conflicted with economic or cultural patterns created by transatlantic exchanges (1 mark)

• Development showing the nature of this conflict (1 mark)

• Identification of a second, distinct policy or initiative (1 mark)

• Explanation of how this policy conflicted with transatlantic exchanges (1 mark)

• Evaluation of how these tensions contributed to colonial resistance, showing a clear causal link (1 mark)