AP Syllabus focus:

‘Second Great Awakening beliefs influenced moral and social reforms and inspired utopian experiments and new religious movements.’

Awakening-Driven Moral Reform and Utopian Movements

The early nineteenth century witnessed widespread religious enthusiasm that reshaped American values, inspired voluntary reform, and encouraged many to experiment with ideal communities aiming to perfect society.

Religious Foundations of Moral Reform

The Second Great Awakening, a nationwide Protestant revival beginning in the late eighteenth century and intensifying through the 1830s, fueled a powerful belief in human perfectibility, the idea that individuals and society could be improved through moral effort and divine grace. This religious surge encouraged ordinary Americans to assume responsibility for personal salvation and community improvement, linking spiritual renewal with social activism.

Human Perfectibility: The belief that individuals and societies can progress morally and spiritually through deliberate effort and reform.

Evangelical preachers such as Charles Grandison Finney emphasized free will, insisting that people could choose righteousness and therefore had a duty to transform society. This democratized religious experience, reinforcing the sense that moral action was both possible and expected. Revival meetings, with their emotional preaching and mass conversions, strengthened networks of believers eager to apply religious convictions to pressing social issues.

Camp meeting of the Methodists in North America, c.1819, depicting an outdoor revival with a preacher addressing a large crowd. Such camp meetings were typical of the Second Great Awakening and helped spread revivalist beliefs that underpinned many moral reform movements. The surrounding tents, platforms, and varied spectators show how these events combined intense religious experience with broad social participation, an extra level of visual detail beyond what the AP syllabus explicitly requires. Source.

Voluntary Societies and Organized Reform

Inspired by revivalist teachings, reformers founded numerous voluntary organizations, groups created outside government to promote collective moral goals. These societies used coordinated messaging, fundraising, and national communication networks to pursue sweeping changes in American life.

Key Functions of Voluntary Societies

Disseminating reform literature to shape public opinion

Organizing local chapters that linked communities across regions

Lobbying legislatures to encourage supportive moral legislation

Mobilizing grassroots activism through lectures, petitions, and rallies

The most widespread reform impulse was the temperance movement, which sought to reduce alcohol consumption, widely seen as a root cause of poverty, domestic violence, and social disorder. Reformers promoted moral suasion, arguing that persuasion—not coercion—could lead individuals to voluntary abstinence. Over time, some groups endorsed legal prohibition, revealing escalating ambitions within the movement.

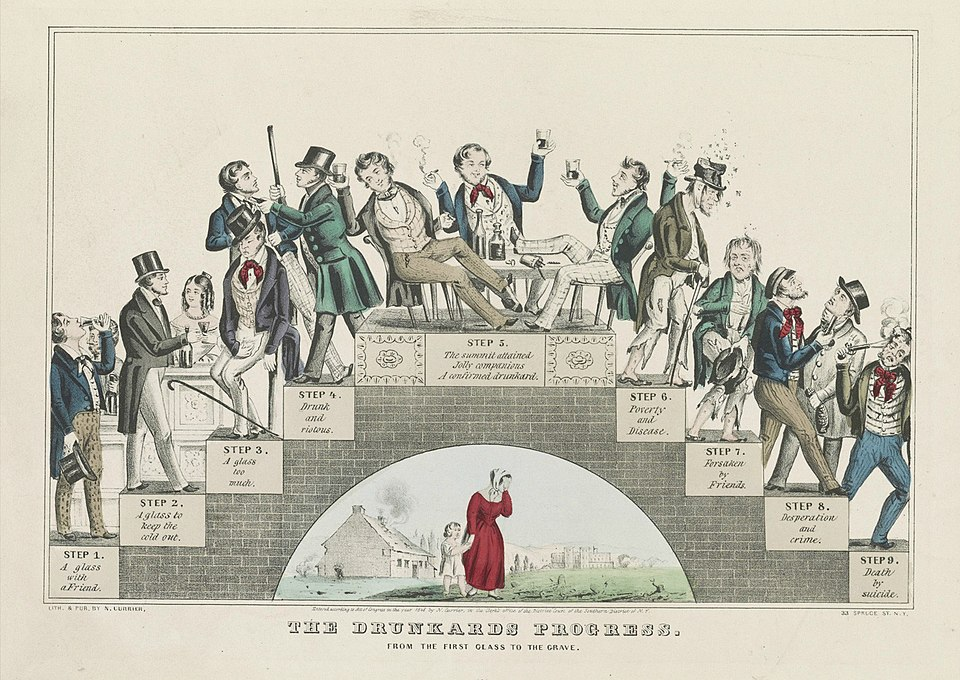

Nathaniel Currier’s “The Drunkard’s Progress” (c.1846) charts the supposed stages from social drinking to poverty, crime, and death. The image embodies temperance reformers’ belief that alcohol led inexorably to moral and social ruin, reinforcing their calls for personal abstinence and, eventually, legal prohibition. The nine labeled steps and dramatic final scene provide more detail and moralistic narrative than the AP syllabus requires, but they clarify how reformers used visual persuasion to support moral reform. Source.

Moral Suasion: A reform strategy that relies on persuasion, appeals to conscience, and public pressure to encourage individuals to change their behavior.

Beyond temperance, revivalist energy also supported reforms in education, prison discipline, and care for the mentally ill. Leaders such as Horace Mann worked to establish tax-supported public schools, while activists like Dorothea Dix campaigned for asylum reform grounded in compassion and rehabilitation.

Utopian Experiments and Communal Ideals

Alongside moral reform came a surge of utopian movements, communities designed to model ideal social relations and escape perceived flaws of mainstream society. These experiments varied widely in structure, but all reflected the revival-era conviction that human society could be reordered along more perfect lines.

Common Motivations for Utopian Communities

Desire to eliminate social inequality or conflict

Rejection of competitive individualism associated with the market economy

Commitment to cooperative labor, shared property, or spiritual unity

Pursuit of environments where moral or religious ideals could be fully realized

One of the most influential groups was the Shakers, led by Mother Ann Lee, whose communities practiced celibacy, communal property, and gender equality. Their distinctive religious worship and craftsmanship gained national attention, illustrating how faith-based ideals could generate structured communal systems.

The Brick Dwelling at Hancock Shaker Village illustrates the orderly, communal architecture of a Shaker utopian settlement. Large, shared residential buildings like this supported celibate, communally organized living and reflected Shaker values of simplicity, efficiency, and spiritual discipline. The modern photograph captures more recent landscaping and signage than students need to know for the AP syllabus, but it accurately represents the historical Shaker built environment. Source.

In contrast, Robert Owen’s New Harmony experiment in Indiana embodied secular utopianism, promoting rationalism, education, and cooperative labor. Although short-lived, it sparked discussions about alternative economic models that countered emerging capitalist norms.

The Oneida Community, founded by John Humphrey Noyes, pursued a theology of perfectionism—the belief that people could achieve a sinless life. The group practiced complex marriage, communal child-rearing, and collective labor, demonstrating how religious ideology could justify unconventional social arrangements. While controversial, Oneida reflected the era’s bold attempts to align daily life with transcendent values.

Reform, Social Tensions, and Cultural Debates

While revival-inspired activism energized many Americans, it also generated debate. Some critics argued that reformers overstepped by imposing their morality on others, particularly as temperance and Sabbatarian movements sought legal restrictions. Others viewed utopian communities as impractical or radical challenges to established gender roles, family norms, and market relationships.

Reform impulses also exposed regional and class divisions. Middle-class evangelicals often led reform efforts, believing they were uplifting the poor or controlling social disorder amid the disruptions of the market revolution. Working-class Americans sometimes resisted, viewing reformers as moralizing outsiders ignorant of economic realities. Meanwhile, utopian experiments attracted both idealists seeking alternatives and detractors who feared social experimentation.

The Broader Significance of Awakening-Driven Reform

The intersection of revivalist religion and social activism transformed American civic life. It encouraged citizens to see moral reform as a collective responsibility and fostered an ethos of voluntary association that became central to American democratic culture. Utopian communities, though often short-lived, demonstrated the era’s willingness to reimagine social structures and experiment with new ways of living.

These movements reflected the AP specification’s emphasis on how Second Great Awakening beliefs inspired moral and social reform, utopian experiments, and new religious movements, shaping a dynamic and evolving society during Period 4.

FAQ

Early charitable work tended to be local, informal, and centred on churches or small community groups. Reform societies of the early nineteenth century introduced more systematic, national strategies.

They used printed tracts, travelling lecturers, subscription networks, annual conventions, and coordinated fundraising, allowing even small towns to connect to a wider moral reform movement.

These methods created a new model of mass participation that shaped later reform campaigns, including abolitionism and women’s rights.

The temperance movement appealed to a wide social range, including clergy, middle-class families, employers, and urban reformers, all of whom associated alcohol with disorder or economic loss.

It also benefited from clear, memorable visual propaganda, simple behavioural demands (abstinence), and the ability to organise both locally and nationally.

By the 1830s, some temperance groups were among the largest voluntary organisations in the country, giving them unprecedented influence.

Many utopian groups consciously tested alternative gender arrangements that challenged mainstream expectations.

Examples include:

• Shared domestic labour in some communities, reducing the traditional gendered division of work

• Leadership roles for women in Shaker villages, where female eldresses held authority

• Experiments in regulated courtship and marriage patterns, such as complex marriage at Oneida, which attempted to reframe emotional and family relationships

These experiments reflected deeper efforts to restructure society at its most intimate levels.

Most communities faced difficulties generating enough consistent income to support all members, particularly when they rejected competitive market practices.

Challenges included:

• Remote rural locations with limited market access

• Reliance on a few trades or crafts vulnerable to economic downturns

• Tension between communal labour ideals and the need for individual specialisation

• The time-intensive nature of religious or ideological practices, reducing productive labour hours

These structural limitations often led to internal strain or eventual dissolution.

Critics often believed reformers imposed narrow moral standards that did not reflect the diversity of American life.

Working-class opponents in particular resented the implication that their habits, leisure activities, or drinking patterns were inherently immoral.

Others argued that reformers’ push for legal restrictions, especially in temperance or Sabbatarianism, threatened personal liberty and local autonomy, revealing early tensions over the limits of moral legislation.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the Second Great Awakening contributed to the rise of moral reform movements in the early nineteenth century United States.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark:

• Identifies a basic link between the Second Great Awakening and moral reform (e.g., it encouraged religious enthusiasm or moral improvement).

2 marks:

• Explains a specific influence, such as the belief in human perfectibility motivating individuals to join reform efforts, or the role of revival meetings in spreading reformist ideas.

3 marks:

• Provides a clear and developed explanation showing how revivalist beliefs directly translated into organised reform activity (e.g., voluntary societies promoting temperance, education, or social discipline), with accurate historical context.

(4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which utopian communities reflected the broader ideals of the Second Great Awakening during the period 1800–1848.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks:

• Identifies at least one way utopian communities reflected revivalist ideals (e.g., communal living, moral discipline, pursuit of perfection).

• Provides some relevant historical detail (e.g., Shakers, Oneida, New Harmony).

• Shows basic reasoning but may be descriptive rather than analytical.

5 marks:

• Develops an argument considering how far these communities embodied Second Great Awakening principles (e.g., emphasis on spiritual purity, rejection of societal corruption, belief in reshaping behaviour).

• Includes specific evidence from at least two communities.

6 marks:

• Offers a well-supported, balanced assessment of the extent of alignment between utopian movements and Awakening ideals.

• Considers variation among communities (e.g., religious vs. secular models; Shakers vs. New Harmony).

• Demonstrates strong analytical reasoning, clear judgement, and consistently accurate historical detail.