AP Syllabus focus:

‘Americans created voluntary organizations to change individual behavior and improve society through temperance and other reform efforts.’

Voluntary reform organizations flourished during the early nineteenth century as Americans, inspired by religious and intellectual movements, mobilized to reshape personal conduct, strengthen communities, and address growing social challenges.

Voluntary Organizations and the Reform Impulse

The Expanding Landscape of Reform Associations

Between 1800 and 1848, the United States witnessed a surge in voluntary organizations—member-driven groups formed outside of government to improve society through collective action. These associations reflected deepening commitments to moral uplift, self-improvement, and social responsibility. Their emergence aligned closely with the democratizing ethos of the Second Great Awakening, which emphasized the individual’s capacity for moral choice and encouraged believers to act on behalf of community welfare.

Many reformers believed that voluntary societies could reach into everyday life more effectively than government institutions. The resulting networks created a vibrant civil society that addressed problems ranging from alcohol consumption to education, poverty, and public health.

Voluntary organization: A non-governmental association formed by individuals who unite to promote shared moral, social, or cultural goals.

These organizations proliferated rapidly, often linking local chapters into national networks that exchanged strategies, publications, and reform philosophies.

Religious Roots and Moral Motivations

The revivalist culture of the Second Great Awakening played a central role in motivating Americans to organize for reform. Evangelical ministers urged congregants to display their faith through benevolent action, arguing that individual salvation should spark moral improvement across entire communities. This religious environment encouraged ordinary Americans—especially women—to see reform as both a spiritual duty and a path to national progress.

Large camp meetings and revivals in places like upstate New York and the Ohio Valley stressed personal conversion, self-discipline, and the duty to improve society.

This 1819 aquatint shows a large Methodist revival gathering where crowds assemble to hear evangelical preaching. It illustrates the mass religious enthusiasm that energized early nineteenth-century reform culture. Such meetings helped develop the organizational habits later used in voluntary reform societies. Source.

Reformers also drew from republican ideology, which stressed that virtuous citizens sustained a healthy republic. Voluntary initiatives thus served both religious and civic aims, linking personal behavior to the nation’s broader moral character.

The Temperance Movement as a Model of Organized Reform

One of the most influential voluntary organizations of this era was the American Temperance Society (ATS), founded in 1826. It aimed to curb excessive drinking by promoting abstinence from alcohol. Temperance reformers argued that alcohol contributed to poverty, domestic violence, unemployment, and public disorder—issues they believed threatened the nation’s moral fiber.

Temperance groups used a range of strategies:

Moral suasion, encouraging individuals to sign pledges of abstinence

Distribution of books, pamphlets, essays, and sermons

Collaboration with churches to promote abstinence through community pressure

Formation of statewide and national federations to coordinate campaigns

Encouragement of public pledges and mass meetings to build momentum

These tactics made temperance one of the largest and most influential reform movements in the United States during the early nineteenth century.

The American Temperance Society (ATS), founded in 1826, became one of the most influential voluntary organizations, coordinating thousands of local auxiliaries that asked members to pledge abstinence.

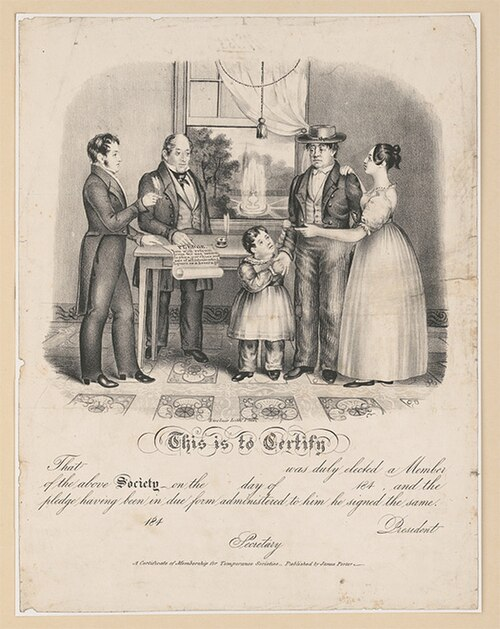

This 1841 membership certificate shows the formal printed document given to participants who pledged abstinence. Its moral and patriotic imagery links alcohol avoidance to family stability and civic virtue. The decorative symbolism exceeds syllabus requirements but clearly represents the strategies temperance societies used to influence behavior. Source.

Women’s Expanding Role in Voluntary Reform

Although political rights for women were extremely limited, voluntary societies became key spaces for women’s participation in public life. Women organized fundraising events, managed charitable networks, created Sunday schools, and staffed literacy programs. These roles allowed them to exercise leadership, public speaking, and administrative skills typically closed off in formal politics.

Women’s moral authority—rooted in the era’s belief in separate spheres—was central to their prominence in reform movements. Many Americans considered women uniquely positioned to guide moral behavior within families and communities, making their activism an extension of their domestic responsibilities rather than a challenge to them.

Education, Literacy, and Benevolent Assistance

Reformers used voluntary organizations to expand educational access for both children and adults. Groups such as the American Sunday School Union and various local literacy societies aimed to teach reading, distribute religious literature, and provide structured weekly instruction. Education was viewed as key to promoting discipline, morality, and economic opportunity.

Other organizations addressed poverty and social welfare. Urban charitable societies delivered food, clothing, and medical aid to struggling families. Many believed that structured charity, combined with moral guidance, would prevent dependency and encourage self-sufficiency.

Moral Regulation and Social Control

While reformers sought to uplift individuals, voluntary organizations also exerted significant social pressure. Their campaigns often aimed to regulate personal behavior through community scrutiny and public pledges. Some historians view these efforts as early attempts at moral regulation, with reformers imposing middle-class norms on workers, immigrants, and the poor.

Even so, voluntary organizations reflected the expanding democratic culture of the era. By relying on persuasion rather than legislation, they underscored the belief that a moral society could be achieved through individual choice and collective action rather than coercive state power.

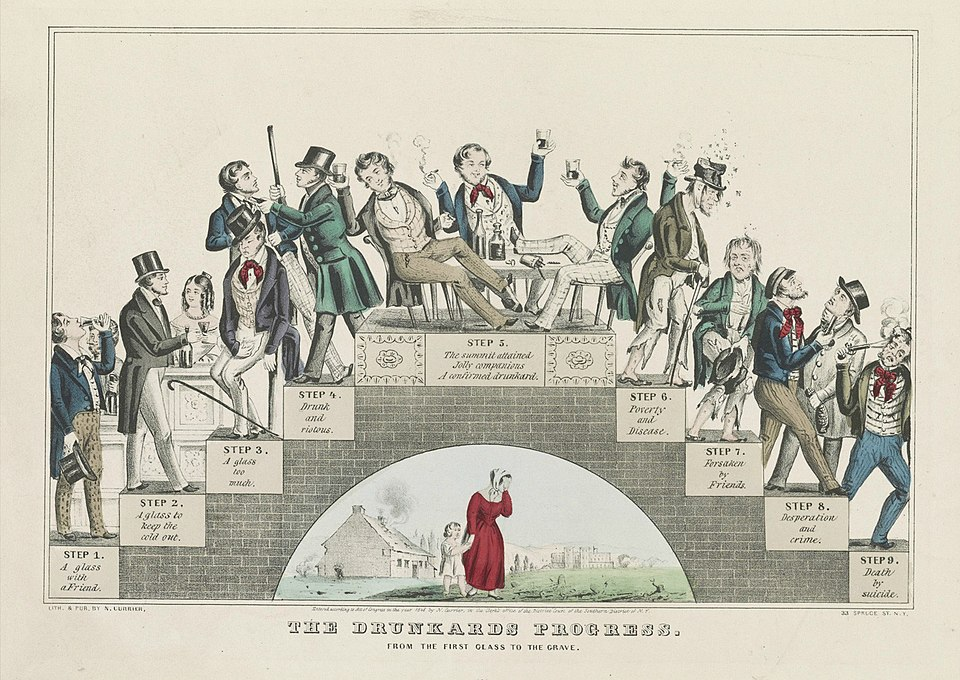

Temperance advocates circulated pamphlets, tracts, public lectures, and striking visual images that dramatized alcohol’s dangers and promised social respectability to those who took the pledge.

This 1846 lithograph depicts nine stages that temperance reformers claimed led from a first drink to poverty and death. Such vivid imagery was used to persuade Americans that abstinence was essential to personal and social stability. The detailed narrative exceeds syllabus requirements but illustrates the movement’s reliance on moral-suasion techniques. Source.

Networks, Communication, and National Reach

The early nineteenth century’s improved transportation and communication—including canals, turnpikes, and expanding postal routes—allowed voluntary societies to coordinate across great distances. National conventions, printed reports, and shared curricula standardized reform messages and strategies. As a result, movements such as temperance, education reform, and moral suasion developed cohesive national identities.

These networks helped forge a more interconnected civic culture. Americans increasingly saw themselves as participants in nationwide reform efforts dedicated to shaping a virtuous, orderly, and morally committed republic.

Reform Organizations as Engines of Social Change

Voluntary societies left a profound imprint on the nation’s moral and social landscape. They mobilized thousands of Americans, fostered new forms of public engagement, and laid groundwork for later movements in abolitionism, women’s rights, and religious philanthropy. Their central purpose—to change individual behavior and improve society—defined a major strand of American reform culture during the period 1800–1848.

FAQ

Early societies relied on handwritten correspondence, itinerant lecturers, and printed circulars that could be shared among towns.

Local chapters often formed spontaneously and then linked informally through ministers, travelling reformers, or printers who circulated shared messages.

Over time, these loose connections evolved into more structured regional associations that standardised pledges, literature, and campaign strategies.

Smaller communities often lacked formal institutions such as police forces, schools, or charitable bodies, making voluntary groups pivotal in shaping public morality and providing support.

Their meetings offered social connection, allowing reform ideas to spread through close-knit networks.

In areas with limited governmental presence, voluntary societies filled a vacuum by coordinating relief, education, and moral initiatives.

Most societies relied on member subscriptions, one-off donations, and community fundraising events.

Some produced and sold inexpensive pamphlets, songbooks, or tracts to generate revenue.

Wealthier reform advocates occasionally acted as patrons, underwriting larger print runs or sponsoring travelling lecturers.

They created substantial demand for cheap printed material, encouraging local printers to expand production of tracts, reports, and moral stories.

Reform groups also helped standardise formats, such as uniform pledge cards and subscription lists.

Their extensive distribution networks contributed to the rise of national circulation patterns in the American publishing industry.

Members gained experience in committee work, financial management, and event organisation.

Public speaking and persuasive communication became common skills through leading meetings or promoting pledges.

Women in particular developed leadership and administrative capabilities that later supported activism in abolition, education, and women’s rights movements.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which voluntary organisations contributed to social reform movements in the early nineteenth-century United States.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark: Identifies a valid contribution of voluntary organisations (e.g., promoted temperance or literacy).

2 marks: Provides brief explanation showing how the organisation contributed to reform (e.g., used moral suasion, distributed tracts, encouraged pledges).

3 marks: Gives a clear and accurate explanation with contextual detail (e.g., mentions the American Temperance Society and its role in reducing alcohol consumption through coordinated national campaigns).

(4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which the growth of voluntary reform organisations between 1800 and 1848 reflected broader religious and cultural developments in the United States. Use specific historical evidence to support your answer.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks: Provides a generally accurate explanation linking voluntary organisations to at least one broader development (e.g., Second Great Awakening or republican ideals). Uses some relevant evidence.

5 marks: Offers a clearer argument with multiple pieces of evidence (such as camp meetings, temperance pledges, women’s benevolent work) and shows how these reflected broader cultural or religious trends.

6 marks: Presents a well-reasoned assessment of the extent of the connection, fully supported with specific and accurate evidence (e.g., revivalist influence, moral suasion strategies, women’s expanding role, national networks of reform societies). Shows clear understanding of continuity and significance within the period.