AP Syllabus focus:

‘Gradual emancipation in the North increased the free African American population, even as many states restricted African Americans’ rights.’

Northern emancipation unfolded unevenly after the American Revolution, expanding the free Black population while leaving African Americans subject to persistent legal, political, and social restrictions across the region.

Northern Emancipation: Gradual Processes and Regional Variation

Northern emancipation did not occur through a single sweeping act but through state-by-state gradual emancipation laws passed from the 1780s into the early 19th century. These laws reflected growing revolutionary-era critiques of slavery but also deep regional caution about fully integrating African Americans into civic life.

Gradual Emancipation Statutes

Most northern states adopted emancipation laws that freed individuals born after the legislation’s passage, often requiring long periods of indentured servitude before legal adulthood. This meant that slavery did not disappear immediately; instead, enslaved populations tapered off over decades. States such as Pennsylvania (1780), New York (1799, 1817), and New Jersey (1804) exemplified this approach.

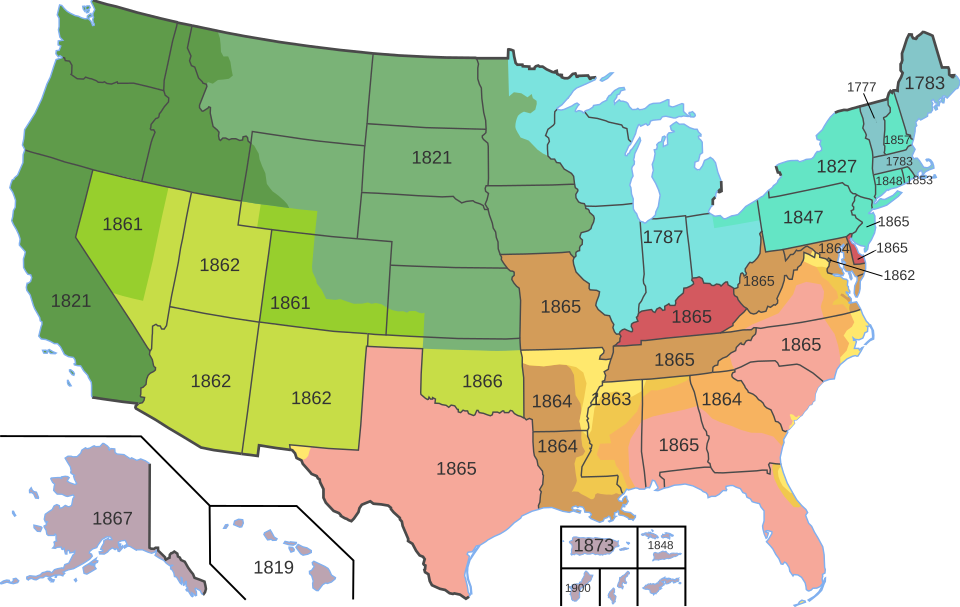

This map shows the abolition of slavery in each U.S. state, color-coded by date and method of abolition. It highlights how northern states moved toward emancipation earlier through gradual-emancipation laws enacted between the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The map also includes later Civil War–era abolition in the South, which exceeds the period 1800–1848 but provides broader national context. Source.

• These laws reflected Enlightenment ideals but also economic pragmatism, allowing households time to adjust to labor changes.

• The phased system produced overlapping generations: enslaved adults continued in bondage while children were legally “free” but bound to long apprenticeships.

• Full abolition in many states did not occur until the 1820s–1840s, meaning northern slavery persisted well into the period covered by this syllabus unit.

Free Black Population Growth

As gradual emancipation unfolded, the free African American population in the North expanded steadily. Census data from the early republic showed thousands shifting from enslaved to free status, strengthening northern Black communities.

• Growing free populations helped create new social, family, and institutional networks in northern cities and towns.

• Emancipation rates varied by state and locality, depending on economic reliance on enslaved labor and political attitudes toward race.

• Larger urban centers such as Philadelphia, New York City, and Boston became important early hubs of free Black life.

Social Realities for Free Black Communities

Although emancipation eliminated legal slavery for most northern African Americans, it did not grant them full citizenship or equality. Free Black communities developed distinctive institutions and cultural forms in response to ongoing exclusion.

Continued Racial Discrimination

Several northern states imposed legal restrictions on African Americans even after they achieved freedom.

• Voting rights were denied or rescinded in states such as New Jersey, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania, limiting African American political participation.

• Laws commonly restricted testifying in court, serving in militias, or attending public schools with White children.

• Many states enacted Black laws requiring registration, proof of freedom, or restrictions on migration from other states.

These political and societal constraints reflected the persistence of racist ideologies and fears of economic competition.

Community Institutions and Self-Help Traditions

Despite barriers, free Black communities created institutions that became foundations of social life and mutual support. Churches, schools, and voluntary associations helped define collective identity and resilience.

Black Churches and Religious Leadership

Independent Black congregations became central pillars of northern free communities, offering spiritual, educational, and political leadership.

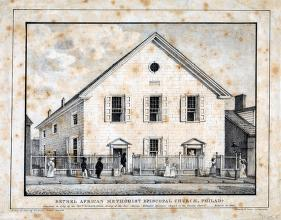

This 1829 lithograph shows the second building of Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, known as “Mother Bethel,” one of the earliest independent Black churches in the United States. It illustrates the emergence of autonomous Black religious institutions that anchored free Black communities in the North. Background details about the artist and later buildings appear on the source page but extend beyond AP U.S. History requirements. Source.

• The African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, founded by Richard Allen in 1816, symbolized the growth of autonomous Black religious institutions.

• Black churches provided safe spaces for worship, literacy instruction, political meetings, and mutual aid.

• Clergy often served as community leaders who articulated visions of racial uplift and collective improvement.

Education and Mutual Aid

Free African Americans organized schools—often operating outside the public system—to ensure educational opportunities for their children.

• Schools taught literacy, numeracy, and vocational skills considered essential for advancement in a racially discriminatory economy.

• Mutual aid societies offered financial assistance, burial services, and support for widows and orphans. These organizations strengthened communal bonds and cultivated leadership skills among free Blacks.

Labor, Mobility, and Economic Opportunity

Economic life for free African Americans in the North was shaped by both growing opportunities and entrenched discrimination.

Employment Patterns

Most free Black men and women worked in low-wage occupations due to discriminatory hiring practices.

• Common occupations included domestic service, dock labor, artisanal trades, and service jobs such as coach driving and catering.

• A small but important Black entrepreneurial class emerged in cities, contributing to community stability and social mobility.

• Economic restrictions reinforced social hierarchies even in regions that condemned slavery.

Geographic Mobility and Urbanization

The growth of free Black communities coincided with increasing urbanization in the early 19th century.

• Cities offered employment opportunities, cultural networks, and access to Black institutions unavailable in rural areas.

• Migrants from the Upper South, fleeing the threat of sale or seeking better prospects, contributed to northern Black population growth.

• This mobility promoted cultural exchange and forged broader regional connections among African Americans.

Political Activism and Early Antislavery Efforts

Free Black northerners became early leaders in activism aimed at expanding rights, resisting discrimination, and challenging the institution of slavery.

Early Political Engagement

Despite widespread exclusion from voting, African Americans used alternative political channels to assert their rights.

• Petition campaigns targeted discriminatory laws and advocated for broader civil rights.

• Activists collaborated with White antislavery allies while also critiquing paternalistic or gradualist approaches.

• Community leaders built a foundation for later 19th-century abolitionist and civil rights activism.

Cultural Assertion and Identity

Free Black communities articulated a distinct cultural and political identity grounded in freedom, resilience, and a vision of racial equality.

• Newspapers, literary societies, and oratory provided platforms for expression and debate.

• Collective identity reinforced the belief that emancipation should lead to full participation in American civic life, even when the broader society resisted that transformation.

FAQ

Gradual emancipation often freed children before their parents, producing families in which some members were legally free while others remained enslaved. This complicated domestic arrangements and could delay reunification.

Free Black families adapted by creating strong kinship networks across households, sharing childcare, labour, and resources. Community institutions such as churches and mutual aid societies became crucial stabilising forces, helping families navigate the uneven transition to freedom.

Free Black leaders frequently submitted petitions to state legislatures, contesting laws that restricted movement, voting rights, and access to public institutions. These petitions framed African Americans as rights-bearing citizens and aimed to reshape public opinion.

Some activists collaborated with sympathetic White reformers, but they also developed independent political strategies through conventions, literary societies, and church networks.

Many northern newspapers depicted African Americans through racist stereotypes, often framing free Black urban neighbourhoods as disorderly or impoverished. Such portrayals reinforced public support for restrictions on movement, voting, and education.

In response, African American writers began publishing letters, pamphlets, and eventually their own newspapers. These publications offered counter-narratives that emphasised industry, respectability, and demands for equal rights.

African American women played central roles in sustaining households, managing informal economies, and participating in church life. Many worked as domestic labourers or ran small businesses that supported community resilience.

Women also established mutual aid societies, sewing circles, and educational initiatives. These organisations provided financial assistance, moral instruction, and social support, strengthening communal cohesion.

Northern states often feared that an expanding free Black population would compete economically with poorer White workers. Politicians also worried about social disorder and responded by limiting rights such as voting, migration, and public schooling.

Racist beliefs about African American inferiority shaped these laws, reflecting how emancipation did not automatically challenge entrenched social hierarchies. These restrictions reveal that freedom and equality advanced at markedly different paces in the North.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks):

Explain one way in which gradual emancipation laws in the northern states affected the development of free Black communities between 1800 and 1848.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for identifying a valid effect (e.g., growth of the free Black population).

• 1 mark for explaining how gradual emancipation produced that effect (e.g., freeing children born after a certain date).

• 1 mark for linking this effect to the formation of institutions or social networks within free Black communities (e.g., development of Black churches or schools).

Question 2 (4–6 marks):

Evaluate the extent to which free African Americans in the North gained greater opportunities after emancipation between 1800 and 1848. In your answer, consider both improvements and continued limitations.

Mark scheme:

• 1–2 marks for describing at least one opportunity (e.g., establishment of independent Black churches, access to education).

• 1–2 marks for describing at least one major limitation (e.g., disfranchisement, segregated schooling, restrictive Black laws).

• 1 mark for providing specific evidence from the period (e.g., reference to AME Church, state voting restrictions).

• 1 mark for a judgement on the overall extent of change, acknowledging both opportunities and restrictions.