AP Syllabus focus:

‘Antislavery and abolitionist movements expanded in the North, pressing to end slavery and challenging the institution’s legitimacy.’

Growing Northern abolitionism between 1800 and 1848 transformed American political and moral debates, as reformers challenged slavery’s legitimacy, organized activism, and mobilized public opinion across expanding networks.

Growth of Northern Abolitionism

Northern abolitionism expanded rapidly in the early nineteenth century as reformers responded to religious revivals, political developments, and evolving ideas about human rights. The Second Great Awakening infused antislavery activism with moral urgency, while economic and demographic changes in the North fostered reform culture. Though movements differed in ideology and strategy, they shared a commitment to exposing slavery as incompatible with American republicanism.

Religious Impulses and Moral Arguments

Evangelical values inspired many reformers to portray slavery as a sin requiring immediate national repentance.

Preachers emphasized individual moral responsibility, arguing that all people bore an obligation to combat injustice.

Revival-influenced activists framed abolitionism as part of a broader effort to perfect society according to Christian egalitarian ideals.

Reformers used sermons, pamphlets, and mass meetings to highlight the spiritual corruption associated with human bondage.

These religious roots helped legitimize antislavery activism for middle-class Northerners and encouraged widespread participation.

Ideological Foundations of Abolitionism

Abolitionists deployed moral, political, and constitutional claims to challenge slavery’s legitimacy in the United States.

Free Labor Ideology

Many Northerners believed in free labor, the idea that economic and social progress depended on voluntary labor and equal opportunity. They argued that slavery threatened national prosperity by undermining democratic values. Likewise, free labor principles positioned slavery as fundamentally opposed to the republic’s founding ideals.

Natural Rights and Republicanism

Abolitionists frequently invoked natural rights, asserting that all individuals possessed inherent liberties that no government could legitimately violate.

Natural Rights: Fundamental liberties that individuals possess by virtue of being human, which governments are obligated to protect.

Drawing on this tradition, activists claimed that slavery contradicted the Declaration of Independence and damaged America’s global reputation. This ideological framing recast slavery not merely as a Southern institution but as a national moral crisis.

Abolitionists also used constitutional arguments, maintaining that the federal government held authority to regulate slavery in territories and suppress the interstate slave trade. Though controversial, these claims helped expand public debate.

Key Organizations and Leaders

Northern abolitionism matured through coordinated movements, influential leadership, and expanding networks.

The American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS)

Founded in 1833, the AASS became the most prominent national antislavery organization.

It promoted immediate emancipation, rejecting gradual approaches common earlier in the century.

The group circulated newspapers, organized lecture circuits, and encouraged local chapters nationwide.

Its extensive print campaigns reached readers across urban and rural communities.

William Lloyd Garrison and Moral Suasion

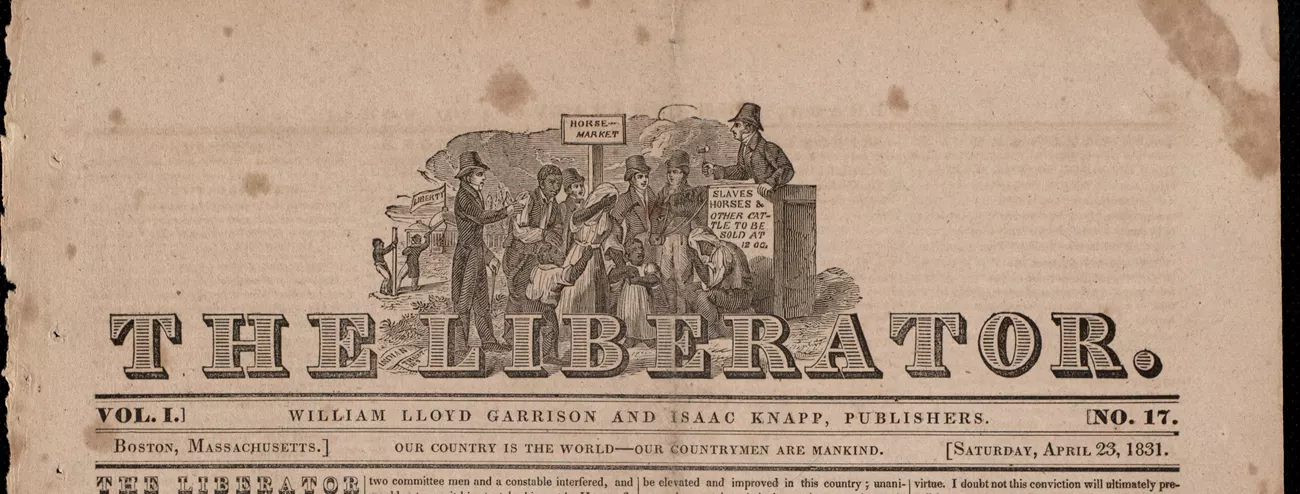

William Lloyd Garrison, editor of The Liberator, advocated moral suasion, the strategy of appealing to consciences through persuasion rather than political institutions.

Moral Suasion: An antislavery strategy that sought to convince individuals and society that slavery was immoral and should end through voluntary action.

Garrison’s uncompromising rhetoric galvanized supporters and critics alike. Although some Northerners viewed his radicalism as divisive, his influence broadened the movement’s visibility.

Black Abolitionists and Community Leadership

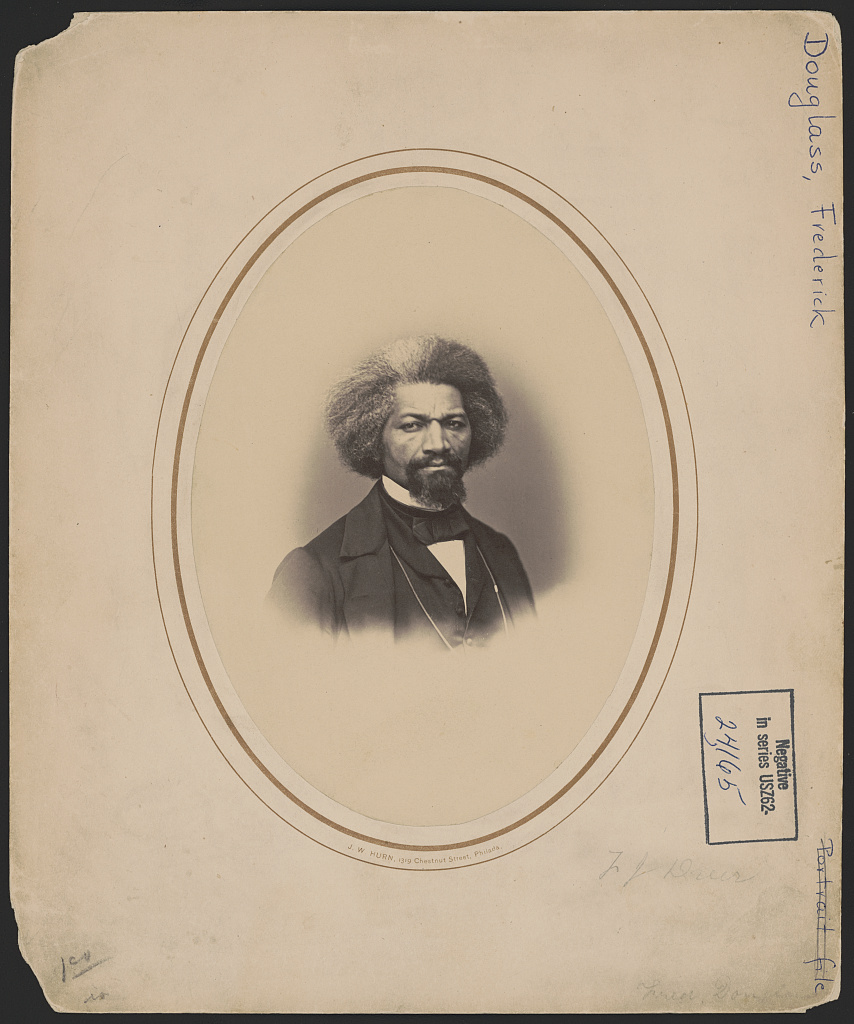

Free African Americans played essential roles in shaping abolitionism. Figures such as Frederick Douglass, Maria W. Stewart, and David Walker offered firsthand testimony about slavery’s brutality and argued for racial equality.

This mid-19th-century photograph shows Frederick Douglass, one of the most influential Black abolitionists in the United States. Douglass’s powerful speeches and writings offered firsthand testimony about slavery and challenged both slavery and Northern racism. The portrait is slightly later than the earliest phase of the movement but accurately represents the mature leader whose activism grew out of the earlier period covered in this subtopic. Source.

They established independent churches, mutual aid societies, and literary associations.

Black abolitionists pushed for inclusion within broader antislavery organizations.

Their speeches and newspapers challenged racism in the North as well as slavery in the South.

Their leadership broadened the movement’s perspective and added powerful moral authority.

Strategies and Activism

Abolitionists developed diverse methods to expand the movement and pressure institutions.

Print Culture and Public Engagement

Antislavery literature circulated widely in Northern states.

Newspapers such as The Liberator and The North Star spread abolitionist ideas.

This engraved masthead from The Liberator shows contrasting scenes of slavery and emancipation, encapsulating the paper’s antislavery message. The image highlights how abolitionists used powerful visual symbolism alongside text to appeal to readers’ consciences. It includes additional allegorical details, such as auctions and celebratory freed people, that extend beyond the syllabus but enrich understanding of abolitionist propaganda. Source.

Pamphlets, broadsides, and sentimental novels highlighted enslaved people’s suffering.

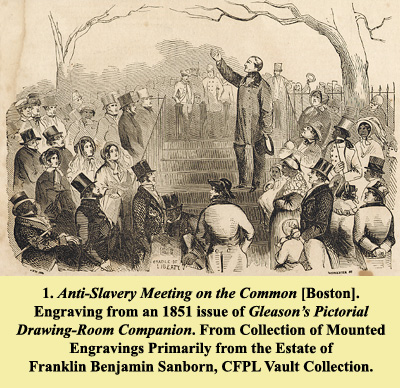

Public lectures and “abolition fairs” raised funds and built community networks.

This engraving depicts an anti-slavery meeting on Boston Common, with an abolitionist speaker addressing a large, attentive crowd. The scene illustrates how Northern reformers used public lectures and open-air gatherings to spread antislavery ideas and mobilize ordinary citizens. Although dated 1851, slightly after the 1800–1848 period, it accurately represents the kinds of meetings emerging from earlier Northern activism. Source.

These efforts created a vibrant reform culture that reinforced shared commitment to antislavery ideals.

Political Action and Petition Campaigns

While some activists rejected politics, others embraced it.

Abolitionists submitted thousands of petitions to Congress demanding abolition in the District of Columbia and opposition to the interstate slave trade.

These petitions provoked the gag rule, which barred antislavery petitions from discussion, illustrating how Northern activism reshaped national political conflict.

The Liberty Party, founded in 1840, became the first national political party committed to ending slavery, signaling growing support for antislavery voting blocs.

Political engagement demonstrated the movement’s increasing organizational sophistication.

Resistance, Violence, and Backlash

Abolitionists faced significant opposition.

Northern mobs attacked antislavery speakers and destroyed printing presses, accusing abolitionists of threatening social order.

Southern leaders condemned the movement, fearing it would incite slave rebellions.

The federal government responded to political pressure with legislation such as the gag rule.

Despite hostility, abolitionism continued to widen its influence.

Broader Impact on Northern Society

The growth of abolitionism reshaped Northern culture and identity. The movement encouraged new discussions about citizenship, racial equality, and moral responsibility. It also intersected with other reform movements, including temperance and women’s rights, as activism taught participants how to organize, advocate, and challenge established norms.

By 1848, Northern antislavery activism had expanded from scattered local efforts into a national force, pressing to end slavery and challenging the institution’s legitimacy.

FAQ

Advances such as cheaper paper, steam-powered presses, and improved transportation networks enabled abolitionists to print and distribute materials more quickly and at lower cost.

These developments allowed even small organisations to circulate newspapers, pamphlets, broadsides, and petitions widely across the North.

Faster printing increased the frequency of antislavery publications.

Railways and postal routes expanded readership beyond major cities.

Lower production costs helped sustain long-running abolitionist newspapers led by both Black and white activists.

Many Northerners feared that abolitionism would disrupt the economic links between Northern industry and Southern cotton, potentially harming local employment and trade.

Racism also played a major role. Some communities opposed abolitionists because they believed emancipation would lead to increased Black migration or social competition.

Political concerns mattered too: critics viewed abolitionists as destabilising actors who threatened national unity and provoked sectional conflict.

Women organised fundraising fairs, circulated petitions, and ran local antislavery societies that connected households to national activism.

They also developed skills in public speaking and leadership, often challenging gender expectations.

Reactions were mixed:

Supporters valued their organisational abilities.

Critics claimed women were overstepping social boundaries by entering political debates.

Petition drives created significant administrative pressure, with thousands of signatures demanding action on slavery in the District of Columbia and the interstate trade.

These petitions forced Congress to confront the issue repeatedly, culminating in the gag rule, which blocked discussion of antislavery petitions altogether.

Although the rule suppressed debate, the controversy heightened national awareness of abolitionist activism and illustrated the movement’s growing political influence.

Lecturers adapted tone, content, and emotional appeal depending on local economic, religious, and social conditions.

In industrial areas, they emphasised free labour ideology and the threat slavery posed to republican values.

In strongly religious regions, they focused on moral arguments rooted in Christian duty.

In racially diverse communities, Black speakers often highlighted lived experience and appeals for equality.

This flexibility allowed abolitionists to build support across varied Northern regions.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one specific way Northern abolitionists attempted to influence public opinion about slavery between 1800 and 1848, and briefly explain why it was effective.

Mark scheme (3 marks total)

1 mark for identifying a specific method (e.g., publication of abolitionist newspapers such as The Liberator; public lectures; petition campaigns; distribution of antislavery pamphlets).

1 mark for explaining how this method reached or mobilised Northern audiences (e.g., widespread circulation, large crowds at meetings).

1 mark for explaining why it was effective in shaping public opinion (e.g., moral arguments resonated with religious reform culture, emotional impact of testimony, increased visibility of antislavery ideas).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which Black abolitionists shaped the development of Northern antislavery activism in the period 1800–1848.

Mark scheme (6 marks total)

1 mark for a clear argument or thesis addressing the extent of influence.

1–2 marks for accurate factual evidence about Black abolitionists (e.g., Frederick Douglass, Maria W. Stewart, David Walker; Black churches; mutual aid societies).

1–2 marks for explaining how their activism shaped the movement (e.g., providing first-hand testimony, advocating racial equality, expanding organisational networks).

1 mark for contextual awareness or nuanced evaluation (e.g., noting collaboration with white abolitionists, limits of racial inclusivity within organisations, or the significance of Black-led initiatives).