AQA Specification focus:

‘The difference between equality and equity in relation to the distribution of income and wealth.’

Understanding the difference between equality and equity is crucial for analysing income and wealth distribution. These terms, though related, represent distinct principles shaping economic policy decisions.

Equality in Distribution

Equality refers to situations where everyone receives the same amount of income or wealth, regardless of their circumstances, effort, or need. This principle is often associated with fairness in numerical or absolute terms.

Equality: The uniform distribution of income and wealth across all individuals, irrespective of differences in needs, contributions, or circumstances.

In practical terms, equality would imply:

All individuals earning identical wages.

Wealth being divided evenly across the population.

No variation in disposable income between different households.

However, such strict equality is rarely pursued in economic systems because it ignores individual circumstances, incentives, and resource requirements.

Equity in Distribution

Equity, in contrast, is focused on fairness rather than sameness. Equity takes into account different needs, starting positions, and contributions. A distribution is considered equitable when it is judged to be just and reasonable, even if it is not numerically equal.

Equity: The fair distribution of income and wealth, considering individual circumstances, needs, and contributions.

An equitable distribution might mean:

Higher support for disadvantaged groups through welfare payments.

Redistribution policies that reduce poverty while allowing for income differentials.

Recognising that some inequality can incentivise productivity, but excessive inequality may be harmful.

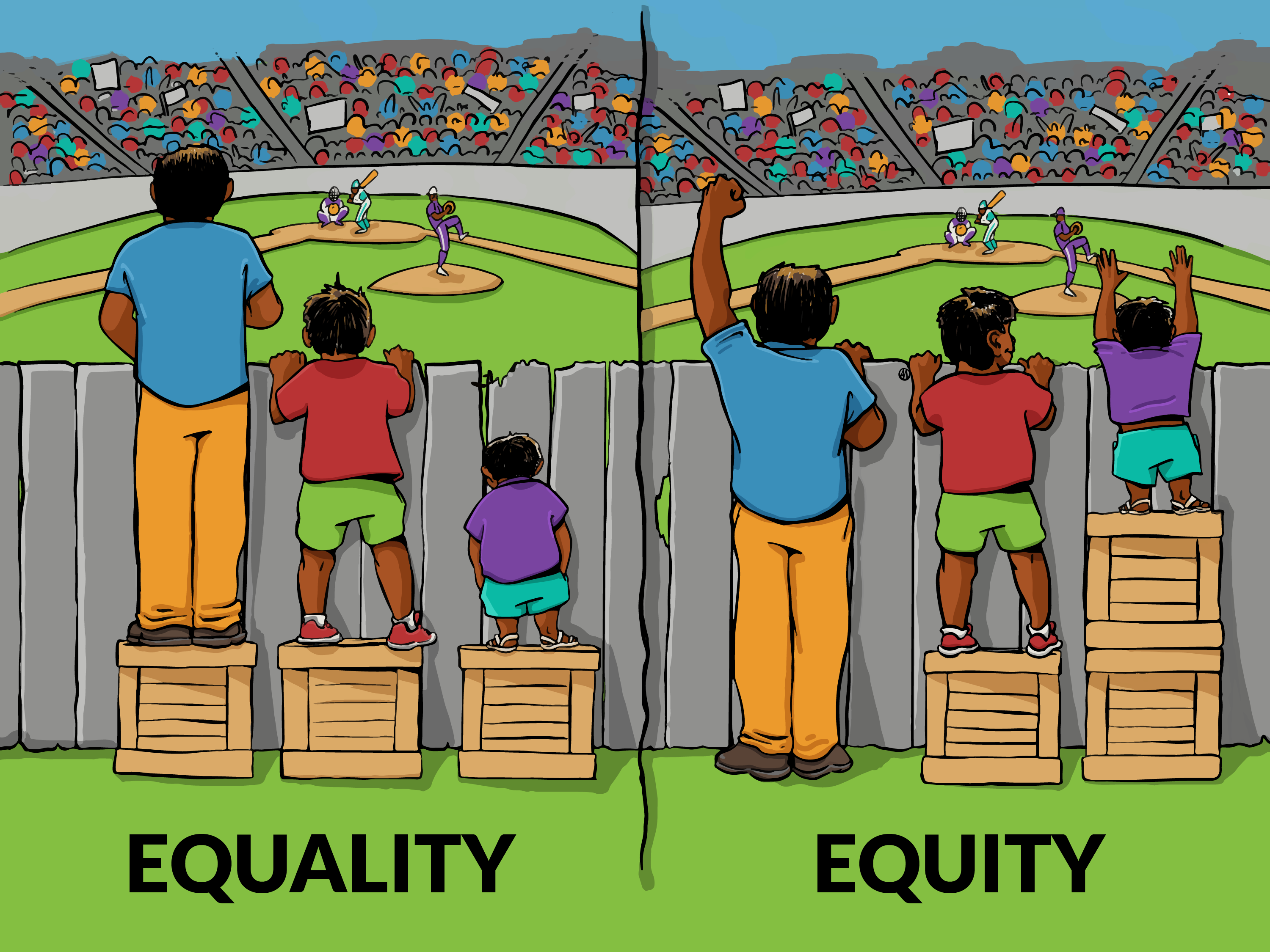

This illustration depicts the difference between equality and equity. Equality provides everyone with the same resources, whereas equity allocates resources based on individual needs to achieve fair outcomes. Source

Equity often requires value judgements, since what one group considers fair may be viewed as unfair by another.

Key Distinction between Equality and Equity

Numerical vs Fairness-Based

Equality: Equal shares for all, regardless of circumstance.

Equity: Adjusted shares based on fairness, considering needs and contributions.

Application in Policy

Equality would imply universal, identical cash transfers.

Equity supports progressive taxation, welfare systems, and targeted social policies.

Example in Labour Markets

Equality: All workers earn the same hourly wage.

Equity: Wages differ, but minimum wages and tax credits ensure workers can achieve a fair standard of living.

Policy Implications of Equality vs Equity

Redistribution and Taxation

Governments must decide whether to prioritise equality or equity when designing redistribution policies:

Policies focused on equality often push for universal benefits (e.g., flat-rate child benefit).

Policies centred on equity tend to apply progressive taxation and targeted benefits to support lower-income households.

Public Services

Equality: Universal access to healthcare and education regardless of income.

Equity: Additional resources directed to disadvantaged areas or groups to level outcomes.

Incentives and Growth

Too much focus on equality can reduce incentives to work, invest, or innovate, potentially slowing growth. Equity, by recognising contributions, attempts to strike a balance between fairness and maintaining incentives.

Economic Perspectives on Equality and Equity

Classical Liberal View

Argues for minimal state intervention.

Prefers equality of opportunity rather than equality of outcome.

Sees equity as ensuring people can compete fairly, but accepts income inequality as a result of merit.

Socialist View

Emphasises reducing inequality of outcome as well as opportunity.

Views equity as requiring redistribution to ensure social justice and prevent exploitation.

Modern Mixed-Economy Approach

Accepts some inequality as inevitable and beneficial for efficiency.

Seeks to achieve equity through welfare states, progressive taxation, and regulation.

Measuring Equality and Equity in Practice

Although equality can be measured numerically (e.g., identical shares), equity requires normative judgement. Economists and policymakers use tools to evaluate how distribution aligns with fairness:

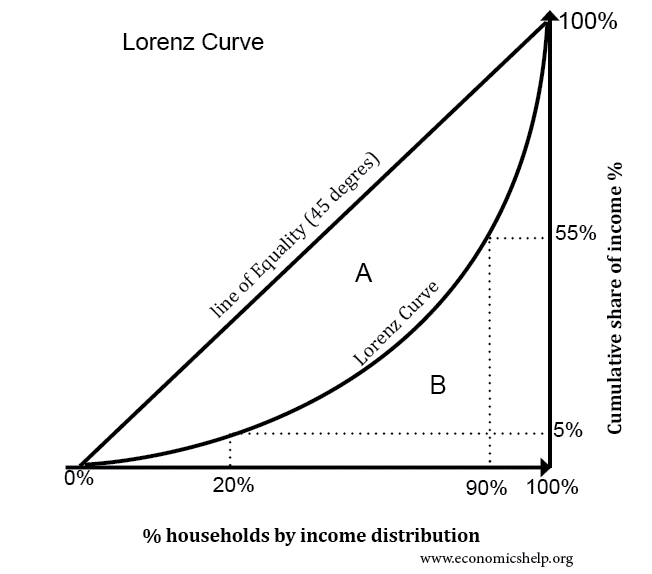

The Gini coefficient measures inequality, but interpreting whether a given value reflects equity involves value judgements.

Policies such as tax credits, welfare, and subsidised services reflect efforts to achieve equity without complete equality.

The Lorenz curve graphically represents income distribution within a population. The curve’s deviation from the line of perfect equality indicates the degree of inequality, with a larger area signifying greater inequality. Source

Value Judgements in Assessing Distribution

Determining whether a distribution is equitable involves subjective assessments:

Some may view progressive taxation as fair because it helps the poor.

Others may see it as unfair because it penalises higher earners.

These differences highlight that equality can be measured, but equity depends on ethical, cultural, and political perspectives.

Why the Distinction Matters

Policymaking: Governments must clarify whether their aim is equality (equal shares) or equity (fair shares).

Social stability: A lack of perceived equity can fuel discontent, even if inequality is numerically reduced.

Efficiency: Striking a balance between equality and equity ensures redistribution does not harm economic incentives.

In summary, equality and equity represent two different approaches to distribution. Equality is about uniformity of outcomes, while equity is about fairness and justice in outcomes. Both concepts shape economic debates, policy design, and broader societal values.

FAQ

Equity requires subjective judgements about what is fair, while equality can be measured numerically. Policymakers must balance competing values and social expectations.

Equity also involves recognising differences in needs, contributions, and circumstances. For example, two households with the same income may have different living standards if one faces higher childcare or healthcare costs.

Equity supports the idea of creating a level playing field rather than equal outcomes. This often means providing additional support for disadvantaged groups to ensure fair chances of success.

Examples include:

Subsidised education in deprived areas.

Extra healthcare provision for vulnerable populations.

Social programmes that target intergenerational poverty.

Cultural norms influence whether societies see equity as redistribution or as rewarding merit.

In collectivist cultures, equity often aligns with strong redistribution policies.

In individualist cultures, equity may focus on ensuring opportunity rather than outcomes.

Thus, fairness is not a universal standard but a reflection of societal values.

Yes. Equity does not demand identical outcomes, only that outcomes are judged fair.

A society may accept wide income gaps if higher earners are seen as contributing more. However, if low-income households cannot meet basic needs, equity is questioned.

Policymakers must clarify whether their goal is equal outcomes or fair outcomes. Without this distinction, policies can be misunderstood or criticised unfairly.

For example:

Universal benefits promote equality but may be seen as inefficient.

Progressive taxation targets equity but may reduce incentives for high earners.

Understanding the distinction helps in evaluating whether a policy aligns with its intended fairness goals.

Practice Questions

Define the difference between equality and equity in the distribution of income and wealth. (3 marks)

1 mark for defining equality as the uniform distribution of income/wealth across individuals regardless of needs or circumstances.

1 mark for defining equity as the fair distribution of income/wealth, considering differences in needs, contributions, or circumstances.

1 mark for explicitly recognising the distinction (equality = sameness, equity = fairness).

Discuss how government policies might aim to achieve equity rather than equality in the distribution of income and wealth. (6 marks)

1–2 marks for identifying relevant policies (e.g., progressive taxation, targeted welfare benefits, means-tested transfers, public service provision to disadvantaged groups).

1–2 marks for explanation of how these policies promote fairness rather than identical outcomes (e.g., extra support for disadvantaged households, redistribution based on needs).

1–2 marks for analysis of the implications (e.g., improved social justice, reduced poverty, maintained incentives compared with strict equality).

Maximum 6 marks awarded for a clear discussion showing understanding of how equity differs from equality in practical policy application.