AQA Specification focus:

‘They should also appreciate that value judgements will influence people’s views of what constitutes an equitable distribution of income and wealth and that these views will influence policy prescriptions.’

The design of policies to tackle inequality and poverty depends not only on economic evidence but also on value judgements, shaping views on fairness and acceptable outcomes.

Understanding Value Judgements in Economics

Economics often deals with positive statements (what is) and normative statements (what ought to be). Value judgements fall within the normative sphere, as they reflect beliefs, ethics, and political ideologies rather than objective evidence. When discussing income and wealth distribution, economists and policymakers inevitably rely on these judgements to decide whether inequality levels are acceptable and what should be done to address them.

Value Judgement: An opinion or belief about what is fair, just, or desirable, influencing decisions and policies beyond objective, measurable evidence.

For example, two economists may agree on the measurement of inequality using the Gini coefficient, but one may argue that redistribution is essential for fairness, while the other may argue it undermines incentives and efficiency.

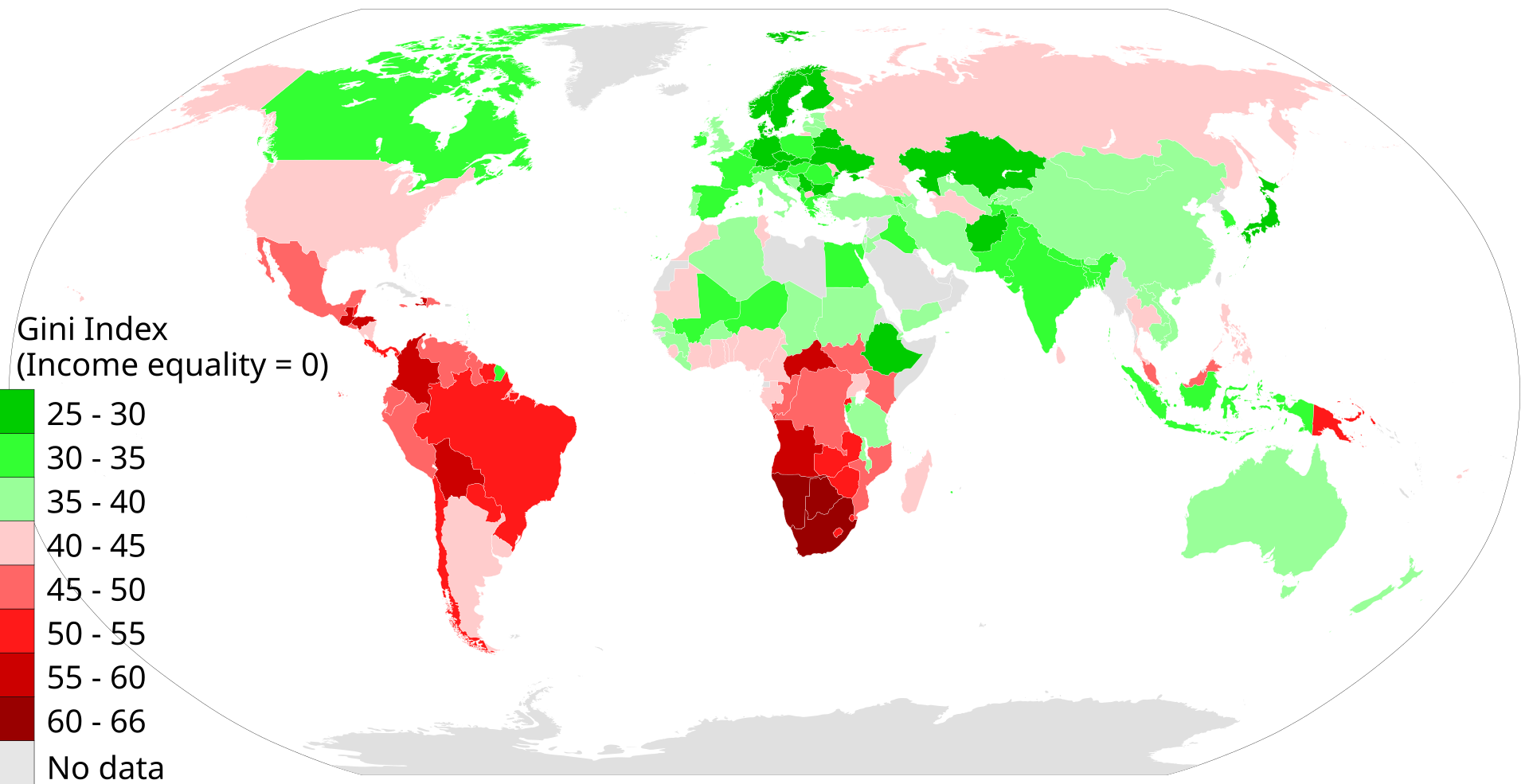

This map depicts the Gini Index of income inequality by country, highlighting global disparities. Higher Gini values indicate greater income inequality, reflecting differing societal values on fairness and equity. Source

Equity and Policy Design

Policy prescriptions depend heavily on how equity (fairness in distribution) is interpreted. There is no universally accepted definition of fairness, so differing interpretations lead to varied policy approaches.

Egalitarian view: Argues for reducing income and wealth gaps, seeing fairness as equal outcomes.

Meritocratic view: Sees fairness as rewards based on effort and contribution, tolerating higher inequality if seen as deserved.

Utilitarian view: Focuses on maximising total welfare, supporting redistribution only if it raises overall well-being.

These perspectives directly shape policies such as taxation levels, welfare provision, and minimum wage legislation.

The Role of Political Ideology

Political beliefs strongly influence value judgements in economics.

Left-leaning ideologies often support progressive taxation, stronger welfare systems, and redistribution policies to reduce inequality.

Right-leaning ideologies often argue for limited government intervention, lower taxes, and policies promoting incentives and efficiency rather than equality.

Centrist positions may favour a balance, tolerating some inequality but intervening to prevent extreme poverty.

Because these beliefs differ, policy debates often go beyond economic data and into political and moral arguments.

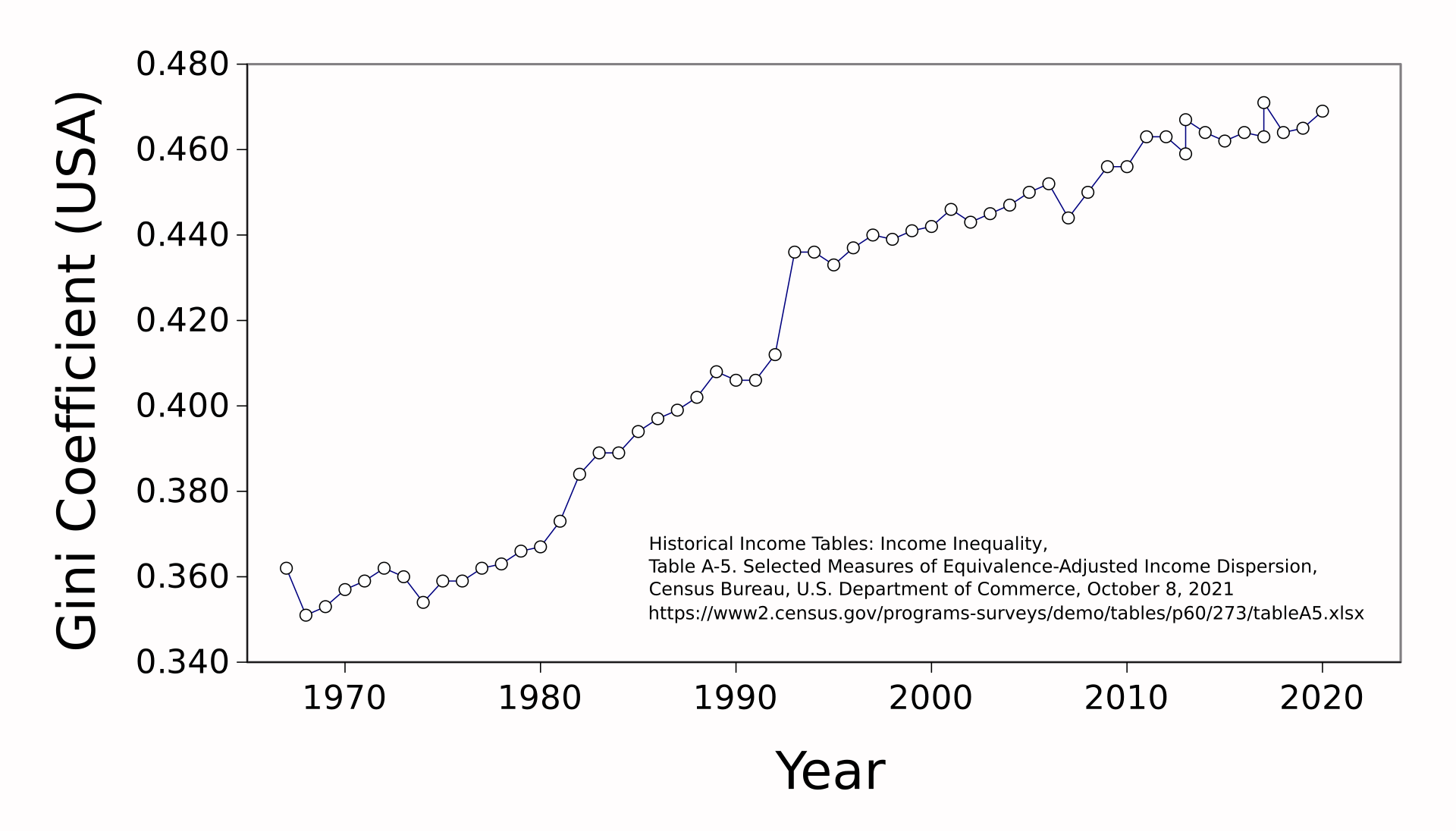

This line graph shows the Gini Coefficient for the United States from 1967 to 2020, reflecting changes in income inequality. The upward trend suggests increasing inequality, which may prompt policy responses based on differing value judgements about fairness. Source

Value Judgements in Redistribution Policies

The design and evaluation of redistribution tools depend on value judgements:

Progressive taxation is justified by those who believe the wealthy should contribute more to society but criticised by others as discouraging enterprise.

Welfare transfers are seen as essential safety nets by some but criticised as fostering dependency by others.

Public services such as education and healthcare can be defended as promoting equality of opportunity, though opponents may argue for private provision.

These debates highlight that economic policies cannot be separated from social and ethical perspectives.

Measuring Inequality vs Judging Equity

Students must recognise the distinction between measurement and assessment:

Measurement involves objective tools like the Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient, which show how unequal a distribution is.

Assessment involves a value judgement, deciding whether the inequality shown by those measures is acceptable or unjust.

Equity: The concept of fairness in economic distribution, which is subjective and shaped by societal, cultural, and political values.

Thus, while data can indicate the level of inequality, only value judgements can determine if policies should be implemented to change it.

Value Judgements and Efficiency Trade-offs

Many policy debates centre on the equity-efficiency trade-off. Policies designed to make distribution more equitable, such as redistributive taxation, may reduce incentives to work or invest, potentially lowering economic growth. Whether such efficiency costs are acceptable depends on value judgements:

Some argue fairness is more important than maximising output.

Others argue economic growth should take priority, even if inequality increases.

International and Cultural Perspectives

Value judgements also vary across countries and cultures. For example:

Scandinavian countries often accept higher taxation for welfare provision, seeing equity as a priority.

The United States tends to tolerate more inequality, reflecting stronger beliefs in meritocracy and individual responsibility.

These cultural differences explain why countries with similar levels of inequality may adopt very different policies.

Influence on Policy Prescriptions

Value judgements shape the policy toolkit chosen by governments:

Taxation policy: Progressive vs regressive systems reflect differing beliefs on fairness.

Welfare policy: Universal benefits vs means-tested support depend on views of entitlement and responsibility.

Labour market policies: Minimum wage levels or trade union rights are influenced by views on fairness of wages and bargaining power.

Bullet point summary of influences:

Political ideology (left, right, centrist)

Ethical frameworks (egalitarian, meritocratic, utilitarian)

Cultural attitudes towards fairness

Views on the equity-efficiency trade-off

Long-Term Implications of Value Judgements

Because value judgements underpin policy design, they can also shape long-term economic and social outcomes. A society that prioritises redistribution may achieve lower poverty and more social cohesion but may face slower growth. A society that prioritises efficiency may achieve higher growth but risk social unrest if inequality becomes excessive. Ultimately, value judgements determine which path is chosen.

FAQ

Economic evidence provides measurable data such as inequality levels or poverty rates. Value judgements, however, reflect beliefs about fairness, justice, and what outcomes should be prioritised.

While evidence can highlight inequality trends, value judgements determine whether governments act on them and what policies are chosen to address perceived unfairness.

Disagreement arises because economists interpret data through different value frameworks.

One may argue redistribution improves fairness and social cohesion.

Another may emphasise the efficiency costs and prefer limited intervention.

Thus, identical evidence can support very different policies depending on the value judgement applied.

Cultural attitudes shape what societies consider equitable. For instance, Scandinavian countries value collective welfare and higher taxation, while the United States often prioritises individual responsibility and meritocracy.

These cultural differences influence how governments and voters judge whether income inequality is acceptable or requires intervention.

Taxation design reflects beliefs about fairness:

Progressive taxation assumes wealthier individuals should contribute proportionally more.

Flat or regressive taxation reflects the view that fairness lies in equal or minimal state interference.

The chosen system depends on whether policymakers prioritise equity or incentives.

Yes, measures of success depend on what outcomes are considered valuable.

Some policymakers emphasise GDP growth and efficiency.

Others prioritise income equality, social mobility, or poverty reduction.

The choice reflects value judgements about which indicators best represent a fair and desirable society.

Practice Questions

Explain what is meant by a value judgement in economics. (2 marks)

1 mark for stating that it is an opinion or belief about what is fair, just, or desirable.

1 mark for recognising that it goes beyond objective evidence or measurable data.

Discuss how value judgements can influence government policy prescriptions on the distribution of income and wealth. (6 marks)

Up to 2 marks for identifying that value judgements are subjective views on fairness and equity.

Up to 2 marks for explaining that these shape whether inequality is considered acceptable or requires government intervention.

Up to 2 marks for applying examples, such as:

Left-leaning governments using progressive taxation and welfare to reduce inequality (awarded if linked to fairness judgement).

Right-leaning governments focusing on incentives and efficiency, accepting higher inequality (awarded if linked to value judgement).

Maximum 6 marks: Balanced explanation with at least one example of how value judgements affect differing policy approaches.