AQA Specification focus:

‘The likely benefits and costs of more equal and more unequal distributions.’

Introduction

The distribution of income and wealth affects economic performance and social stability. Understanding the benefits and costs of equality and inequality is central to policy.

The Benefits of a More Equal Distribution

Economic Stability

A more equal distribution of income and wealth tends to reduce the risk of economic and social instability. With wider access to resources, aggregate demand is stronger and more sustainable.

Households on lower incomes usually have a higher marginal propensity to consume (MPC), meaning more equal income distribution supports steady consumption.

A reduction in extreme inequality lowers the risk of recessions caused by insufficient demand.

Poverty Reduction

Greater equality directly reduces relative poverty, helping more individuals access education, healthcare, and housing. This can enhance human capital in the long term.

Human capital: The skills, knowledge, and experience possessed by individuals, which contribute to their economic productivity.

Improved human capital benefits both firms and the economy as a whole, leading to higher productivity and innovation.

Social Cohesion

When wealth and income are more equally shared, societies typically experience greater levels of social cohesion and lower crime rates. People are more likely to feel fairness and legitimacy in institutions, reducing political unrest.

Economic Growth Potential

By improving access to education and training, more equal distributions help unlock the potential of individuals who might otherwise be excluded from contributing productively. This creates a broader base for innovation and entrepreneurship.

The Costs of a More Equal Distribution

Reduced Incentives

Critics argue that greater equality can reduce incentives for individuals and firms to innovate, take risks, and invest. If high earners face steep taxation to redistribute wealth, they may feel discouraged.

Incentives: Factors that motivate individuals or firms to behave in a certain way, often linked to rewards or punishments.

This reduction in incentives can slow down productivity growth, innovation, and overall economic efficiency.

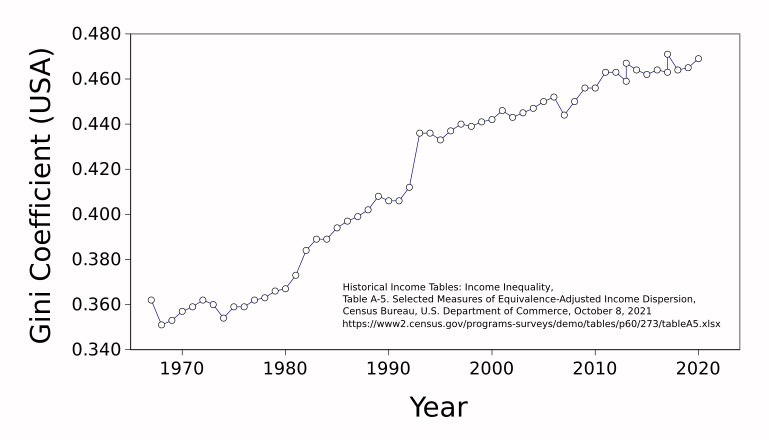

This graph illustrates the trend of income inequality in the United States as measured by the Gini Coefficient from 1967 to 2020. An increasing trend indicates rising income inequality, which can have implications for economic stability and social cohesion. Source

Administrative Costs

Policies to enforce greater equality, such as progressive taxation or welfare transfers, require government administration. These can create deadweight losses if resources are misallocated.

Risk of Dependency

Redistribution through welfare and transfers may create dependency traps, where individuals rely on benefits rather than seeking employment. This can weaken the labour market and reduce overall efficiency.

The Benefits of a More Unequal Distribution

Strong Incentives for Effort

Some inequality can act as a motivator for individuals to work harder, innovate, or invest. The possibility of higher returns provides an incentive to take risks and develop new ideas.

Entrepreneurs are rewarded with profits for creating successful businesses.

Skilled professionals are motivated to train and specialise.

Capital Accumulation

Those with higher incomes save and invest more, providing funds for capital projects and technological progress. This can contribute to long-run economic growth through higher investment levels.

The Costs of a More Unequal Distribution

Social Instability

Excessive inequality often fuels resentment, crime, and political unrest. This can undermine social cohesion, leading to strikes, protests, or even systemic instability.

Inefficient Resource Allocation

When wealth is highly concentrated, it may be spent on luxury goods rather than necessities. Since the wealthy have a lower marginal propensity to consume, aggregate demand may weaken, leading to underutilisation of resources.

Intergenerational Inequality

A highly unequal society risks creating entrenched divisions where the wealthy pass on opportunities to their children, while the poor remain excluded. This reduces social mobility and wastes human potential.

Social mobility: The ability of individuals to move up or down the economic and social ladder compared with their parents.

Low social mobility reduces the fairness of economic systems and can harm long-term growth.

Market Failure Links

Inequality may lead to market failure by excluding large parts of the population from access to healthcare, education, or credit markets. This leads to underinvestment in human capital and prevents efficient outcomes.

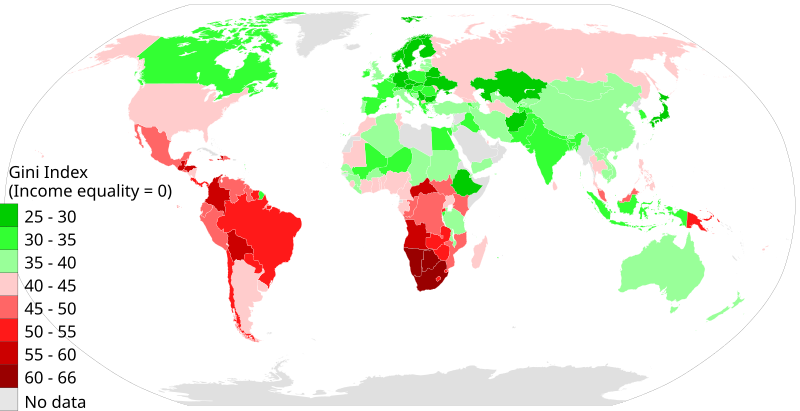

This map displays the Gini Index of income inequality by country as of 2014, with lower values indicating more equal income distribution and higher values indicating greater inequality. The map provides a global overview, though the syllabus does not require country-level comparisons. Source

Balancing Equality and Inequality

Optimal Level of Inequality

Economists recognise that some degree of inequality is necessary for growth and innovation, but excessive inequality is damaging. The challenge for policymakers is finding the balance.

Too much equality: risks reducing incentives and slowing growth.

Too much inequality: risks instability, poverty, and inefficiency.

Policy Considerations

Governments often use a mix of progressive taxation, transfer payments, and public services to influence distribution. Each approach carries benefits and drawbacks in terms of efficiency, fairness, and administrative feasibility.

FAQ

In economies with a more equal distribution, aggregate demand tends to be higher and more stable because lower-income households spend a greater proportion of their earnings.

When income is highly unequal, demand may rely heavily on credit or spending by the wealthy, making growth less sustainable. Over time, this can increase volatility in the economy.

Entrepreneurs are often motivated by the possibility of financial rewards. If redistribution through high taxation significantly reduces these rewards, risk-taking may decline.

This can discourage investment in new businesses, reduce technological progress, and ultimately limit productivity growth in the economy.

Taxation influences incentives and redistribution:

Progressive taxes reduce post-tax inequality but may weaken incentives to work or invest.

Lower taxes on the wealthy may encourage savings and investment but can increase inequality.

The balance depends on how governments design tax systems and whether revenue is used effectively for public services.

Unequal societies often limit access to quality education and healthcare for poorer households. This restricts skill development and reduces productivity potential.

By contrast, a more equal distribution ensures broader opportunities, which helps expand the workforce’s overall skills base and economic output.

Yes. Excessive inequality can reduce consumption, forcing households to rely on debt. This makes economies more vulnerable to financial crises.

Additionally, high inequality can trigger political instability, leading to strikes, protests, or policy uncertainty. These disruptions affect investment and long-term economic performance.

Practice Questions

Define the term social mobility and explain why it may be affected by an unequal distribution of income and wealth. (2 marks)

1 mark for a correct definition of social mobility: the ability of individuals to move up or down the economic and social ladder compared with their parents.

1 mark for explanation: inequality can reduce opportunities for poorer households, limiting access to education, healthcare, and jobs, thereby lowering social mobility.

Discuss the likely economic costs of a more unequal distribution of income and wealth in the UK. (6 marks)

1–2 marks: Identification of relevant costs (e.g., reduced social cohesion, weaker aggregate demand, reduced social mobility).

1–2 marks: Explanation of how these costs arise (e.g., high inequality reduces spending since the wealthy have a lower marginal propensity to consume).

1–2 marks: Application to the UK context (e.g., reference to trends in UK inequality, intergenerational poverty, or potential market failure in healthcare/education).

To achieve full marks, responses must demonstrate clear development of at least two distinct costs with economic reasoning.