OCR Specification focus:

‘Illustrate variable oxidation states, coloured ions and catalytic behaviour, with examples and industrial relevance.’

Transition elements show distinctive chemical behaviour because of partially filled d-subshells, leading to variable oxidation states, coloured compounds and important catalytic roles across laboratory and industrial chemistry.

Overview of Characteristic Properties

Transition elements (particularly Ti–Cu) differ from s-block and p-block elements because their d orbitals are close in energy to the outer s orbitals. This gives rise to several characteristic properties that are central to OCR A-Level Chemistry.

These properties include:

Variable oxidation states

Formation of coloured ions and compounds

Catalytic behaviour

Each property is closely linked to the electronic structure of transition metal atoms and ions and is widely exploited in chemical processes.

Variable Oxidation States

Transition elements commonly form ions with different oxidation states because both the 4s and 3d electrons can be lost or shared in bonding.

Oxidation state: The hypothetical charge an atom would have if all bonds were ionic.

The small energy difference between 4s and 3d orbitals allows different numbers of electrons to be involved in bonding, producing multiple stable oxidation states.

Examples include:

Iron: Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺

Copper: Cu⁺ and Cu²⁺

Chromium: Cr²⁺, Cr³⁺ and Cr⁶⁺

Vanadium: V²⁺, V³⁺, V⁴⁺ and V⁵⁺

Vanadium is a clear example: its common aqueous oxidation states +2, +3, +4 and +5 give distinctly coloured solutions.

Test tubes showing vanadium in different oxidation states, each producing a distinct solution colour. This demonstrates variable oxidation states and the formation of coloured ions in transition metal chemistry. Source

Lower oxidation states are often stabilised by ligands that donate electron density, whereas higher oxidation states tend to form compounds with highly electronegative elements such as oxygen.

Industrial relevance is significant:

Iron cycles between Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ in redox systems, including corrosion and biological processes.

Chromium(VI) compounds are used in oxidising agents and pigments, though they are toxic and carefully controlled.

Variable oxidation states also allow transition metals to participate readily in redox reactions, a key reason for their catalytic activity.

Coloured Ions and Compounds

Many transition metal ions form coloured solutions and solids, unlike most s-block compounds, which are colourless.

The colour arises from electronic transitions within the d-subshell when light is absorbed.

d–d transition: The promotion of an electron between split d orbitals after absorbing visible light.

In a complex ion, surrounding ligands create an electrostatic field that splits the d orbitals into different energy levels. When visible light is absorbed, electrons move between these levels, and the complementary colour is observed.

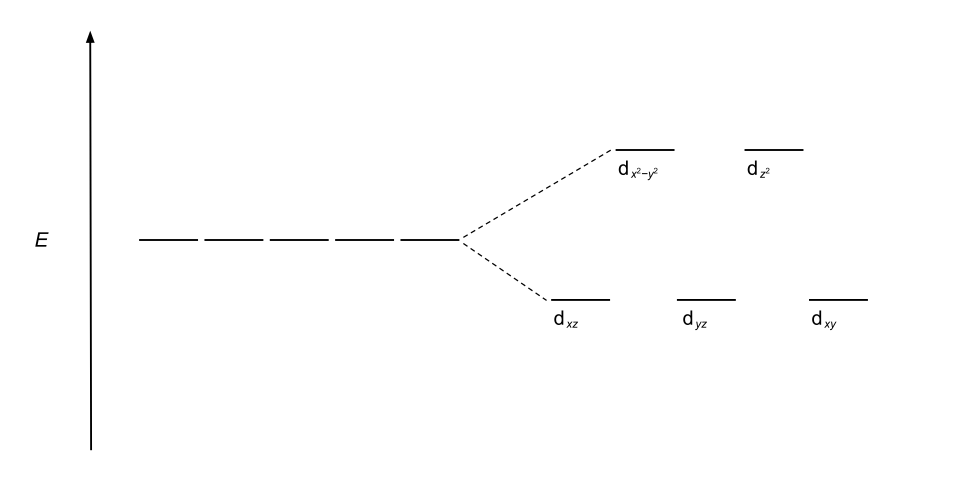

In many complexes, ligands split the five d orbitals into two energy levels, so electrons can absorb visible light to move between them.

An octahedral crystal-field splitting diagram showing how d orbitals split into two energy levels. Absorption of light matching the energy gap (Δo) leads to d–d transitions and observed colour in many transition-metal complexes. Source

Examples of coloured ions:

[Cu(H₂O)₆]²⁺: pale blue

[Fe(H₂O)₆]²⁺: pale green

[Fe(H₂O)₆]³⁺: yellow-brown

Cr³⁺ compounds: typically green or violet

The exact colour depends on:

The metal ion

The oxidation state

The ligand type

The coordination geometry

These colour changes are highly useful in:

Qualitative analysis of metal ions

Monitoring ligand substitution reactions

Identifying oxidation state changes in redox reactions

Catalytic Behaviour

Transition elements and their compounds are widely used as catalysts, both in industry and in the laboratory.

Catalyst: A substance that increases the rate of a chemical reaction without being used up.

Transition metals are effective catalysts because they:

Have variable oxidation states, allowing electron transfer

Can form temporary complexes with reactants

Provide alternative reaction pathways with lower activation energy

Catalysis can occur via two main mechanisms.

Heterogeneous Catalysis

The catalyst is in a different phase from the reactants, usually a solid with gaseous reactants.

Key examples:

Iron in the Haber process for ammonia production

N₂ and H₂ adsorb onto the iron surface, weakening bonds and allowing reaction.Vanadium(V) oxide (V₂O₅) in the Contact process

Catalyses the oxidation of SO₂ to SO₃ in sulphuric acid manufacture.

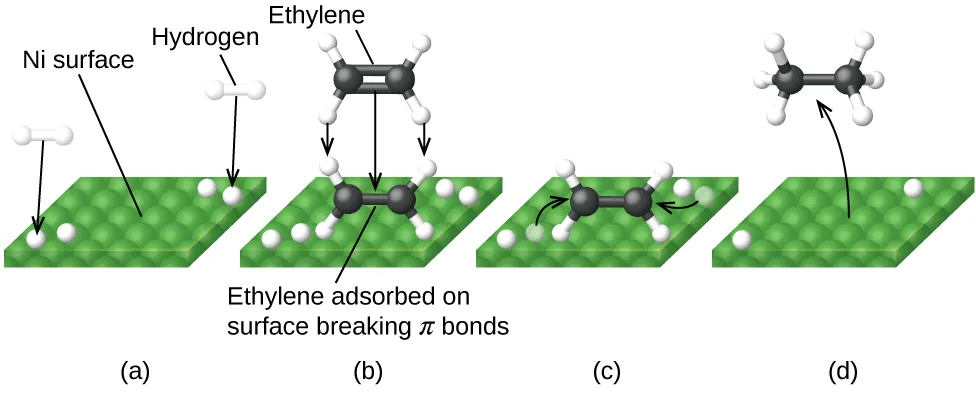

In heterogeneous catalysis, reactants adsorb onto a transition-metal surface, react there, and products then desorb, leaving the catalyst unchanged overall.

Diagram illustrating heterogeneous catalysis on a metal surface, showing adsorption, surface reaction, and desorption of products. The example uses hydrogenation on nickel, but the surface-process mechanism applies generally to transition-metal catalysts. Source

The large surface area of solid catalysts provides sites for adsorption and reaction.

Homogeneous Catalysis

The catalyst and reactants are in the same phase, usually aqueous solution.

Examples include:

Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ catalysing the reaction between iodide ions and peroxodisulfate

Mn²⁺ catalysing redox reactions involving hydrogen peroxide

In homogeneous catalysis, the transition metal ion forms intermediate species, cycling between oxidation states during the reaction.

Industrial and Practical Importance

The characteristic properties of transition elements make them indispensable in chemical industries.

Key applications include:

Chemical manufacturing (ammonia, sulphuric acid, polymers)

Environmental chemistry, including catalytic converters

Biological systems, such as iron in haemoglobin and enzymes

Analytical chemistry, using colour changes and redox behaviour

These properties arise directly from partially filled d orbitals and are central to understanding transition metal chemistry at A-Level.

FAQ

Transition metal ions can appear colourless if no d–d transitions are possible. This occurs when the d sub-shell is either completely empty or completely full.

Examples include:

Sc³⁺ (3d⁰)

Zn²⁺ (3d¹⁰)

In these cases, there are no available d orbitals of slightly higher energy for electrons to be promoted into, so visible light is not absorbed.

Changing the oxidation state alters the number of d electrons and the charge on the metal ion.

This affects:

The size of the electrostatic field created by the metal ion

The extent of d-orbital splitting caused by ligands

As a result, the energy gap between split d orbitals changes, so different wavelengths of light are absorbed, producing different observed colours.

Transition metals can readily gain and lose electrons because they have multiple accessible oxidation states.

This allows them to:

Accept electrons from one reactant

Transfer electrons to another reactant

The metal cycles between oxidation states without being consumed, enabling redox reactions to occur more rapidly through alternative pathways.

Different ligands produce different degrees of d-orbital splitting.

Factors affecting ligand influence include:

Charge on the ligand

Ability to donate electron density to the metal ion

Stronger-field ligands cause greater splitting, leading to absorption of higher-energy light and changes in the observed colour, even for the same metal ion and oxidation state.

Transition metal catalysts participate in reactions by forming temporary intermediate species.

During catalysis:

Bonds form between the metal and reactants

These bonds break as products form

At the end of the reaction cycle, the metal returns to its original chemical state, allowing it to catalyse further reactions without being permanently changed.

Practice Questions

Explain why transition elements often show variable oxidation states.

(2 marks)

Award marks as follows:

1 mark for stating that transition elements have both 4s and 3d electrons available for bonding or loss.

1 mark for explaining that the small energy difference between 4s and 3d sub-shells allows different numbers of electrons to be lost or shared, leading to different oxidation states.

Transition elements commonly form coloured compounds and are widely used as catalysts in industry.

Explain both of these characteristic properties, referring to electronic structure and giving relevant examples.

(5 marks)

Award marks as follows:

Coloured compounds (3 marks):

1 mark for stating that colour arises from d–d electronic transitions.

1 mark for explaining that ligands split the d orbitals into different energy levels.

1 mark for explaining that absorption of visible light promotes an electron between split d orbitals, with the complementary colour observed.

Catalytic behaviour (2 marks):

1 mark for explaining that transition elements can act as catalysts because they have variable oxidation states or can form intermediate complexes.

1 mark for giving a correct example of a transition metal catalyst with industrial relevance, such as iron in the Haber process or vanadium(V) oxide in the Contact process.

Maximum 5 marks.