OCR Specification focus:

‘Explain ligand substitution reactions, colour changes, and haemoglobin’s ligand exchange with O₂ and CO.’

Ligand substitution reactions explain colour changes in transition metal complexes and underpin biological systems such as haemoglobin, where ligand exchange enables oxygen transport and poisoning by carbon monoxide.

Ligand Substitution Reactions

What is Ligand Substitution?

Ligand substitution reactions are central to the chemistry of transition metal complexes and arise from the ability of metal ions to accept different ligands into their coordination sphere.

Ligand substitution: A reaction in which one or more ligands in a complex ion are replaced by different ligands without changing the oxidation state of the metal ion.

These reactions typically occur in aqueous solution and are often reversible, establishing equilibria rather than proceeding to completion. The metal–ligand bonds broken and formed are coordinate (dative covalent) bonds.

Conditions Affecting Ligand Substitution

The extent and speed of ligand substitution depend on several factors:

Nature of the ligand

Stronger ligands form more stable coordinate bonds and can displace weaker ligands.Concentration of incoming ligand

Excess ligand shifts the equilibrium towards substitution.Charge and size of the metal ion

Higher charge density strengthens metal–ligand attraction.Temperature

Increased temperature generally increases reaction rate.

These reactions are commonly observed through distinct colour changes, making them useful in qualitative analysis.

Colour Changes in Ligand Substitution

Origin of Colour Changes

Transition metal complexes are coloured due to d–d electronic transitions, where electrons absorb visible light to move between split d-orbitals. Changing the ligand alters the ligand field strength, modifying the energy gap between d-orbitals.

Stronger field ligands cause a larger splitting, changing the wavelength of light absorbed and therefore the observed colour. Ligand substitution reactions are therefore often identified visually.

Example: Copper(II) Complexes

Copper(II) ions in water exist as the hexaaquacopper(II) complex, which is blue. Substitution of water ligands by ammonia produces a deep blue complex.

This occurs in stages:

Initial addition of ammonia forms a pale blue precipitate due to hydroxide formation.

Excess ammonia dissolves the precipitate, forming a deep blue tetraammine complex.

The observed colour change reflects the altered ligand environment around the Cu²⁺ ion.

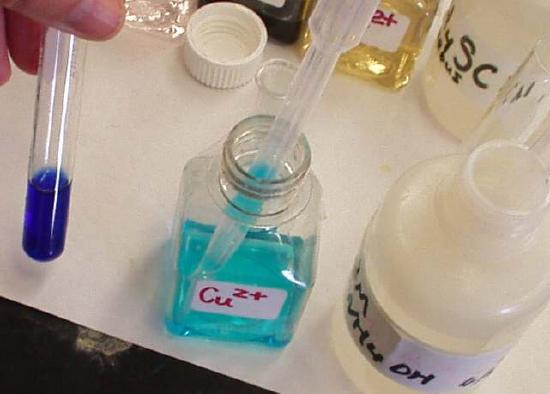

When aqueous ammonia is added to a pale blue copper(II) aqua solution, ligand substitution produces an intensely deep blue copper–ammine complex.

This image shows the colour change when ammonia substitutes for water ligands around Cu²⁺. The deeper blue colour reflects formation of a copper(II) ammine complex with a different ligand environment. Source

Reversibility and Equilibria

Ligand substitution reactions are often reversible and governed by equilibrium principles. For example, increasing the concentration of one ligand shifts the equilibrium towards the complex containing that ligand.

This reversibility is crucial in biological systems, where rapid ligand exchange must occur under controlled conditions.

A clear understanding of equilibrium behaviour helps explain why some ligands bind preferentially but can still be displaced.

Haemoglobin as a Transition Metal Complex

Structure and Role of Haemoglobin

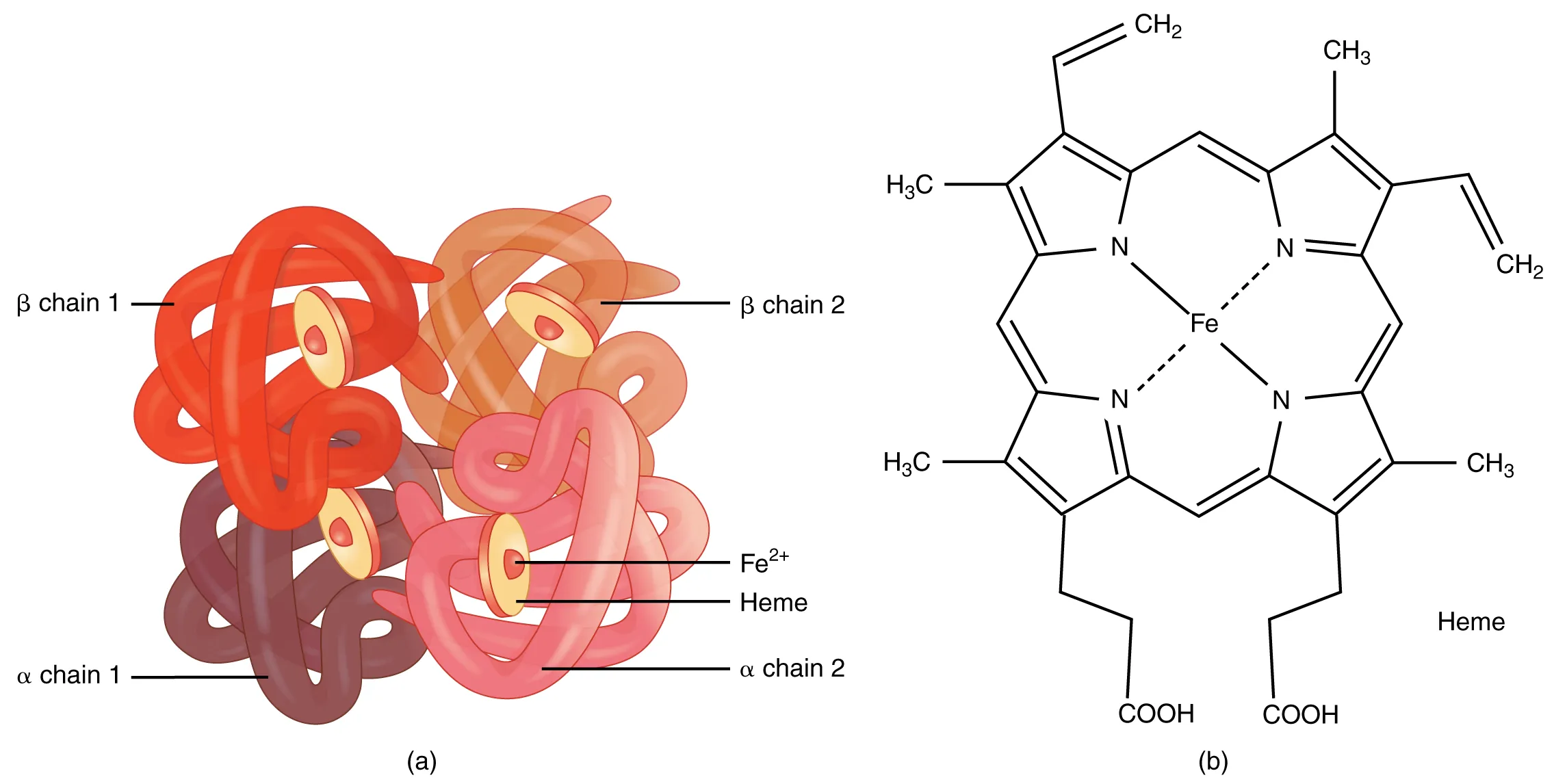

Haemoglobin is a biological coordination complex found in red blood cells. Each haemoglobin molecule contains four haem groups, each centred around an Fe²⁺ ion.

The iron(II) ion:

Is coordinated to a porphyrin ring (four nitrogen atoms)

Has one coordination position occupied by a nitrogen from a protein chain

Has one remaining site available for ligand binding

This sixth coordination site is crucial for oxygen transport.

Oxygen Binding and Ligand Exchange

Haemoglobin contains Fe²⁺ in a haem group, and oxygen binds reversibly at the metal centre to form oxyhaemoglobin.

This diagram illustrates haemoglobin’s structure and highlights haem groups containing Fe²⁺ ions. Each iron centre can reversibly bind one oxygen molecule, acting as a coordination site for ligand exchange. Source

Oxygen binding equilibrium = Hb + O₂ ⇌ HbO₂

Hb = haemoglobin

O₂ = oxygen molecule

HbO₂ = oxyhaemoglobin

This equilibrium must be finely balanced:

Oxygen must bind strongly enough for transport

Oxygen must be released readily to respiring tissues

The reversibility of ligand substitution allows haemoglobin to function efficiently under varying oxygen concentrations.

Carbon Monoxide Poisoning

Competitive Ligand Binding

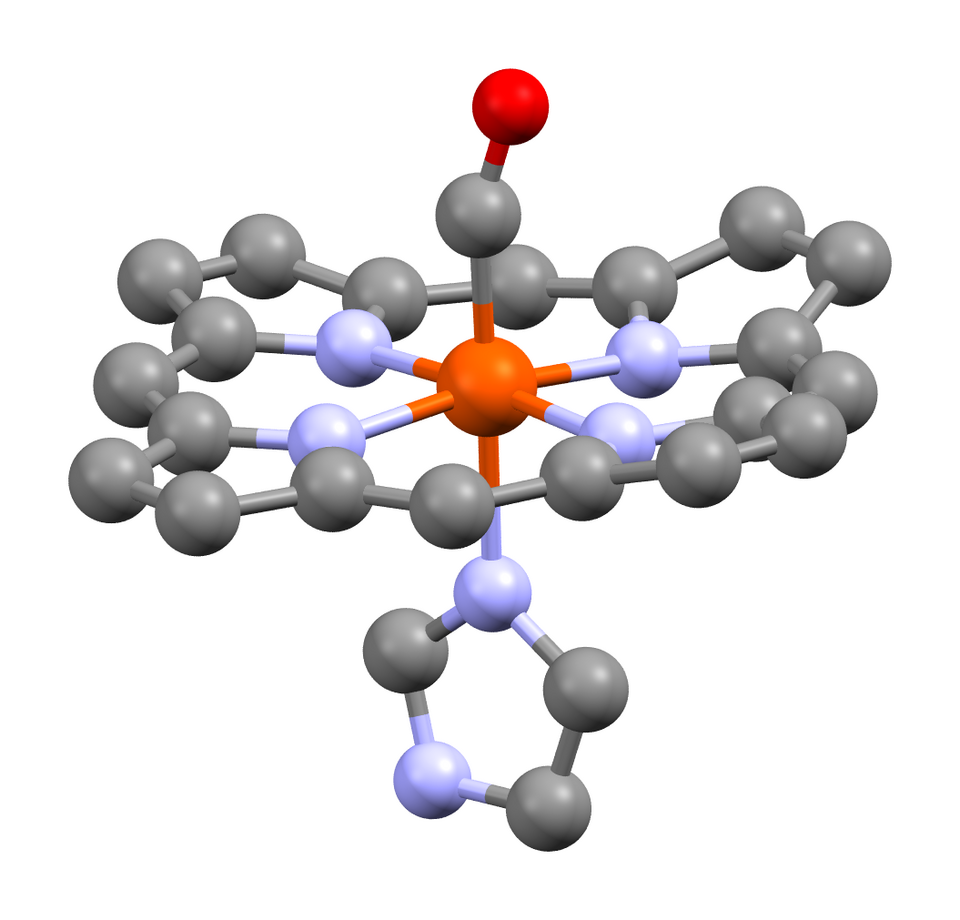

Carbon monoxide (CO) competes with oxygen for the same binding site on the iron(II) ion. However, CO acts as a much stronger ligand.

Carbon monoxide binding = Hb + CO ⇌ HbCO

CO = carbon monoxide

HbCO = carboxyhaemoglobin

Carbon monoxide binds approximately 200 times more strongly than oxygen. This forms a very stable complex that prevents oxygen binding.

Consequences of CO Binding

Haemoglobin becomes unavailable for oxygen transport

Even small amounts of CO significantly reduce oxygen delivery

This explains the high toxicity of carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide forms carboxyhaemoglobin because CO binds strongly to the haem iron and can replace O₂ at the binding site.

This structure shows carbon monoxide coordinated directly to the haem iron as a ligand. It demonstrates how CO occupies the same binding site as oxygen, preventing oxygen transport in the blood. Source

The effect is a direct consequence of ligand substitution principles applied to a biological system.

Ligand Substitution and Biological Control

Haemoglobin demonstrates how ligand substitution reactions can be precisely regulated in living organisms. Protein structure influences ligand access, binding strength, and release.

Key features include:

Reversible ligand substitution

Selectivity for specific ligands

Sensitivity to ligand concentration

These same principles underpin many transition metal reactions studied in inorganic chemistry, highlighting the importance of ligand substitution beyond the laboratory.

Summary of Key Concepts

Ligand substitution involves replacement of ligands without changing oxidation state.

Colour changes arise from altered d-orbital splitting.

Reversible equilibria control substitution reactions.

Haemoglobin functions through controlled ligand exchange with O₂.

Carbon monoxide poisoning is explained by stronger ligand binding.

This subsubtopic links coordination chemistry directly to real-world biological and health-related applications, reinforcing the relevance of transition metal chemistry.

FAQ

Ligands differ in their ability to donate a lone pair to the metal ion.

Key factors include:

Strength of the metal–ligand bond

Size and charge of the ligand

Availability of lone pairs for bonding

Ligands that form stronger coordinate bonds are more likely to replace weaker ligands in substitution reactions.

Haemoglobin must both bind and release oxygen efficiently.

Reversibility is achieved because:

The Fe2+–O2 bond is strong enough for transport but weak enough to break

Changes in oxygen concentration shift the equilibrium

Protein structure limits overly strong ligand binding

This balance allows oxygen uptake in the lungs and release in respiring tissues.

The protein environment controls ligand access to the iron centre.

It:

Restricts which molecules can approach the haem iron

Stabilises bound oxygen through weak intermolecular interactions

Prevents irreversible oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+

This fine control ensures selective and reversible ligand binding.

Carbon monoxide forms a stronger coordinate bond with iron(II).

This is because:

CO is a better electron pair donor than O2

It forms a more stable linear bond with the iron centre

The resulting complex has lower energy than oxyhaemoglobin

As a result, CO displaces oxygen in ligand substitution reactions.

Many biological molecules rely on metal ions for function.

Ligand substitution enables:

Transport of small molecules

Regulation of enzyme activity

Controlled release and uptake of substances

These processes rely on the same coordination chemistry principles seen in transition metal complexes studied in A-Level Chemistry.

Practice Questions

Explain what is meant by a ligand substitution reaction and state one visible observation that may indicate this type of reaction has occurred in a transition metal complex.

(2 marks)

1 mark for stating that a ligand substitution reaction involves one ligand being replaced by another ligand in a complex ion, with no change in oxidation state of the metal ion.

1 mark for stating a correct visible observation, such as a colour change of the solution.

Haemoglobin contains iron(II) ions and can bind both oxygen and carbon monoxide.

(a) Explain, in terms of ligand substitution, how oxygen binds to haemoglobin.

(b) Carbon monoxide is poisonous. Use ligand substitution principles to explain why carbon monoxide reduces the oxygen-carrying capacity of haemoglobin.

(5 marks)

(a) Oxygen binding (2 marks)

1 mark for stating that oxygen acts as a ligand and binds to the iron(II) ion in the haem group.

1 mark for stating that this binding is reversible, allowing oxygen to be transported and released.

(b) Carbon monoxide poisoning (3 marks)

1 mark for stating that carbon monoxide competes with oxygen for the same binding site on the iron(II) ion.

1 mark for stating that carbon monoxide is a stronger ligand than oxygen.

1 mark for explaining that carbon monoxide forms a more stable complex (carboxyhaemoglobin), preventing oxygen from binding or being transported.