AP Syllabus focus:

‘Article V created an amendment process: proposals require a two-thirds vote in both houses or two-thirds of state legislatures, and ratification requires approval by three-fourths of the states.’

Article V sets the formal rules for changing the U.S. Constitution.

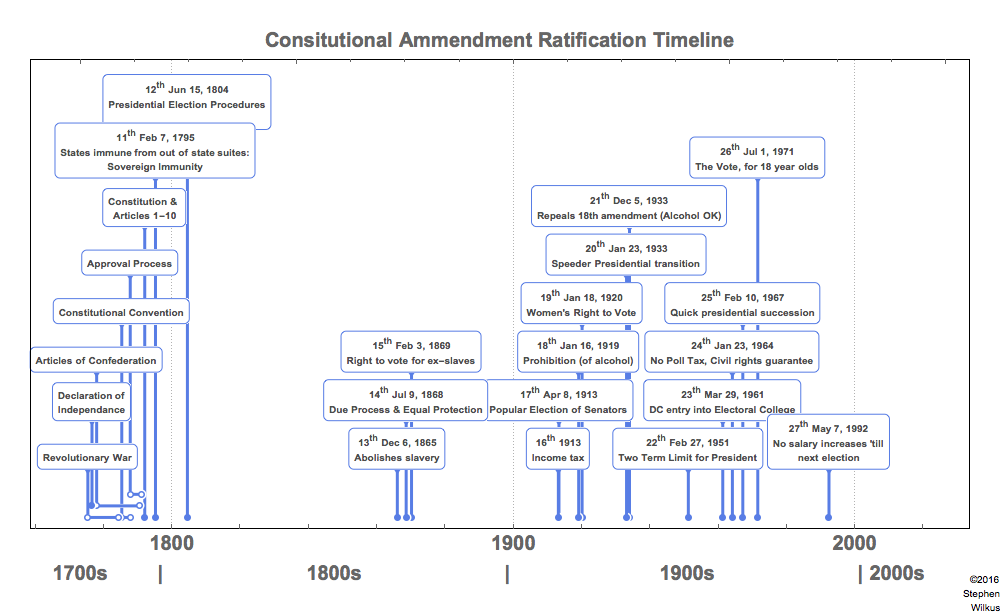

This timeline plots the ratification dates of the U.S. Constitution and all 27 amendments, illustrating how infrequently constitutional change occurs. It helps connect Article V’s supermajority requirements to the historical reality that amendments typically require long-term, broad political agreement. Source

It balances flexibility and stability by requiring unusually broad agreement before an amendment can be proposed and then ratified.

What Article V Does

Article V creates a structured, legally binding method to add constitutional amendments—changes that become part of the Constitution with the same authority as the original text.

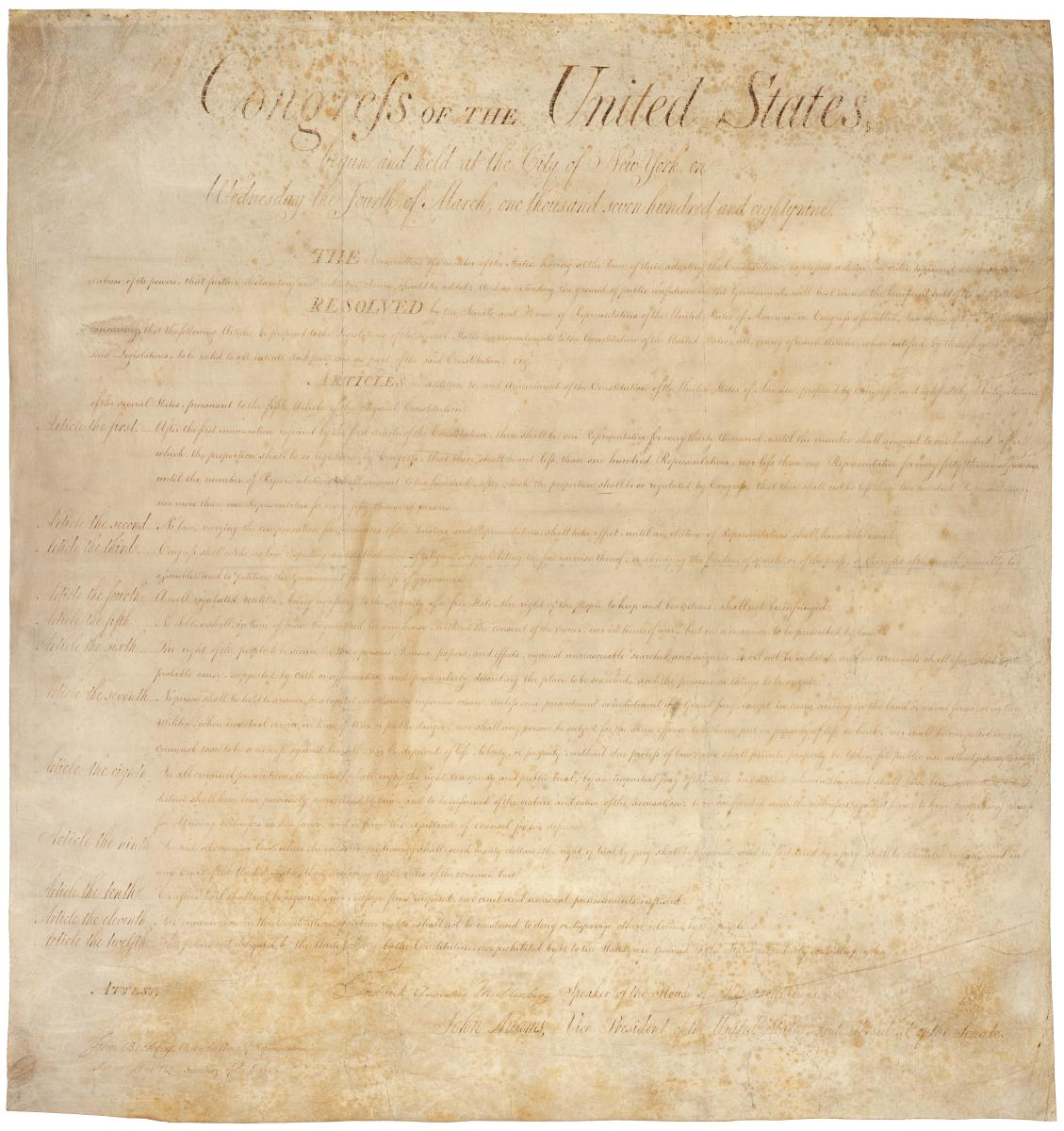

This document is the Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments added to the Constitution after ratification. It serves as a primary-source example of how Article V’s process results in formal constitutional text with equal authority to the original Constitution. Source

Amendment: A formal change or addition to the Constitution adopted through the procedures in Article V.

Because the Constitution is the supreme governing framework, Article V’s design intentionally makes change difficult, encouraging broad national consensus rather than narrow, temporary majorities.

Step 1: Proposing an Amendment

An amendment may be proposed in one of two ways. Either route produces a proposed amendment text that then goes to the states for ratification.

Method A: Proposal by Congress (Most Common)

A proposed amendment must receive a two-thirds vote in both houses of Congress:

House of Representatives: of members voting

Senate: of senators voting

Key implication: proposal requires bicameral supermajorities, so a large cross-party and cross-regional coalition is usually necessary.

Method B: Proposal by a National Convention (Never Used)

Congress must call a convention to propose amendments if two-thirds of state legislatures request it.

The convention may propose one or more amendments, which then proceed to ratification.

Key implication: states can initiate constitutional change even if Congress is unwilling, but uncertainty about convention rules (scope, delegate selection) makes this method politically risky and therefore rare.

Step 2: Ratifying an Amendment

After proposal, Article V requires state-level ratification by three-fourths of the states. Congress chooses which of the two ratification methods will be used.

Method A: Ratification by State Legislatures (Common)

Approval by three-fourths of state legislatures is required.

This method channels ratification through each state’s representative lawmaking body, reinforcing the federal principle that states play a central role in constitutional change.

Method B: Ratification by State Conventions (Rare)

Approval by three-fourths of state conventions is required.

Conventions are specially elected bodies called for the single purpose of considering ratification.

This method can be used when Congress believes public sentiment may differ from existing state legislative preferences, or when lawmakers face conflicts of interest.

Why Article V Uses Supermajorities

Article V’s high thresholds reflect competing goals:

Stability: prevents frequent, partisan, or impulsive constitutional change.

Legitimacy: amendments gain authority when supported by an unusually broad coalition.

Federalism: states are essential gatekeepers through the three-fourths ratification rule.

Protection of minority rights: supermajorities can slow changes that would harm vulnerable groups.

At the same time, these requirements can make it difficult to address widely recognised problems when agreement is intense but not widespread enough across states.

Limits and Congressional Control Within Article V

Within the amendment process, Congress has important procedural influence:

It selects the mode of ratification (legislatures or conventions).

It typically sets deadlines for ratification (a political choice shaping feasibility).

It receives and recognises states’ ratification actions as part of the formal process.

Article V also contains one explicit subject limit still relevant today: no amendment may deprive a state of equal representation in the Senate without that state’s consent.

FAQ

No. Under Article V, proposal is not enough; it must be ratified by $3/4$ of the states using the method Congress specifies.

Uncertainty about:

delegate selection and apportionment

whether the agenda can be limited

procedures for drafting and voting on proposals

The Constitution is silent. The legal effect is disputed and has been handled inconsistently in political practice.

Congress and executive officials play roles in recognising and certifying ratifications, but disputes can raise complex legal questions.

To bypass entrenched state lawmakers, reduce conflicts of interest, or better capture public opinion through specially elected delegates.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Identify two different methods by which an amendment can be proposed under Article V.

1 mark: States proposal by vote in both houses of Congress.

1 mark: States proposal via a convention called by Congress on application of of state legislatures.

(6 marks) Explain how Article V’s proposal and ratification requirements reflect the goals of stability and federalism.

1 mark: Explains stability via supermajority thresholds making change difficult.

1 mark: Links stability to requirement in Congress or of states for a convention.

1 mark: Explains federalism via the decisive role of states in ratification.

1 mark: Links federalism to state approval requirement.

1 mark: Explains Congress’s role in choosing ratification method as a procedural feature within Article V.

1 mark: Uses accurate constitutional language (proposal vs ratification) with clear logical connection to stability/federalism.