AP Syllabus focus:

‘Political negotiation and compromise at the Constitutional Convention shaped the constitutional system; agreements were needed to secure support from diverse states and interests.’

The Constitutional Convention was a bargaining forum as much as a drafting meeting. Delegates brought sharply different interests, and the Constitution’s structure reflects negotiated trade-offs necessary to build a workable national framework acceptable to enough states.

Core idea: constitution-making required bargaining

Compromise was necessary because the delegates faced a dual challenge:

Designing a stronger national government than the Articles of Confederation

Winning broad acceptance among states with conflicting priorities so the plan could plausibly be adopted and obeyed

In practice, this meant writing rules for power that multiple sides could tolerate, even if no one side got everything it wanted.

Compromise: A negotiated agreement in which parties accept less than their ideal outcomes in order to reach a decision and maintain cooperation.

Why the delegates could not simply “vote and move on”

Diverse state interests made “one-size-fits-all” impossible

Delegates represented states that differed in:

Population size (large vs. small states)

Economic structure (commercial vs. agricultural priorities)

Regional concerns (different labour systems and policy preferences)

Political culture (varying comfort with centralized authority)

Because the Convention depended on continued participation and eventual state approval, persistent “winners” and “losers” risked collapse of the meeting or rejection afterward.

Conflicting theories of representation and authority

A central disagreement was what legitimate representation should look like in a republic:

Some delegates wanted government to reflect the people more directly (often aligning with population-based influence).

Others emphasized state equality and feared domination by larger states.

Compromise became the mechanism for reconciling competing claims about where political legitimacy comes from—people, states, or a blend of both.

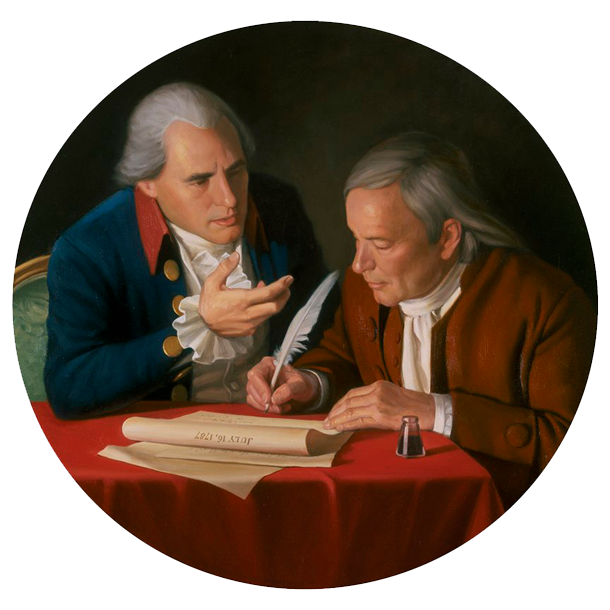

This painting depicts the Connecticut (Great) Compromise, the agreement that resolved the Convention’s most dangerous impasse over representation. It visually reinforces the idea that the Constitution emerged from bargaining: proportional representation in the House paired with equal state representation in the Senate. Use it to connect abstract “legitimacy” debates to a concrete institutional trade-off. Source

The practical problems compromise had to solve

Creating energy in government without recreating tyranny

Many delegates agreed the Articles were too weak, but disagreed on how strong the new system should be. Compromise was needed to balance:

Effective national capacity (taxing, enforcing laws, coordinating policy)

Limits on power to prevent abuses (institutional restraints and divided authority)

This tension pushed delegates toward arrangements that checked power while still allowing action, rather than choosing pure centralization or pure decentralization.

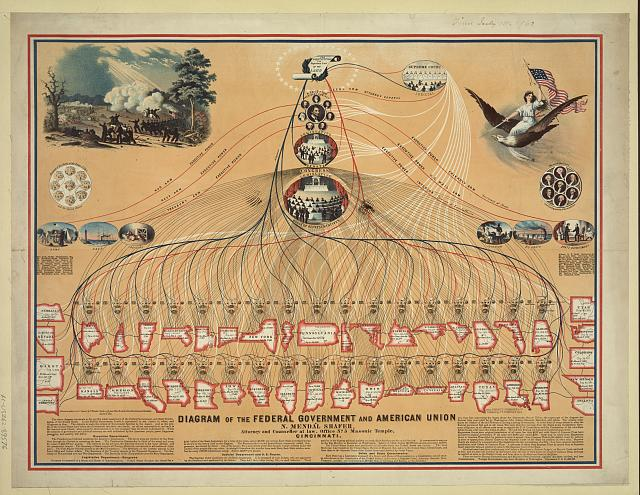

This historical organizational chart lays out the federal government’s major components and explicitly distinguishes the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. It helps students see how the Constitution institutionalizes both capacity and constraint by distributing authority across separate institutions. Pair it with your discussion of preventing tyranny through “institutional restraints and divided authority. Source

Building a system that could endure disagreement

The Constitution had to function when groups disagreed—something the Articles handled poorly. Compromise supported durability by encouraging:

Shared stakes in the system (multiple sides see their interests reflected somewhere)

Mutual veto points or protections that reduce fear of permanent defeat

Broad legitimacy, making compliance more likely even after policy losses

Preventing walkouts and preserving the coalition

The Convention’s authority was politically fragile. If major blocs believed the process was stacked against them, they could withdraw support. Agreements were therefore needed to:

Keep negotiating partners at the table

Avoid deadlock on foundational design questions

Maintain a pathway to eventual public and state acceptance

Compromise as a design feature, not just a tactic

Trading across issues to reach agreement

Delegates often had to accept packages of decisions rather than isolated wins. This style of bargaining mattered because constitutional rules are interconnected:

Changing one power relationship can alter others

Institutions must operate together (not as separate “policy choices”)

The result was a constitutional system shaped by negotiated balances—strong enough to govern, yet structured to reassure skeptics.

Legitimacy required consent from varied constituencies

Because adoption depended on support across multiple states and political communities, compromise served a legitimacy function:

It signalled inclusion of different interests

It reduced perceptions of a constitution “imposed” by a single faction

It increased the likelihood that opponents would still accept the system as lawful

What to remember for AP analysis

When explaining why compromise was necessary, connect:

Diversity of interests (state size, region, economy, political values)

Fear of concentrated power vs. desire for effective governance

Need for consent to make the new framework stable and acceptable

FAQ

Secrecy reduced public posturing and allowed delegates to change positions without immediate backlash.

It also encouraged exploratory bargaining, where tentative offers could be tested and revised before becoming commitments.

Committees could draft “middle-ground” text after hearing competing proposals.

They also simplified debate by presenting fewer options to the full Convention, making agreement more achievable.

State delegations often cast votes as blocs, which raised the leverage of swing states and internal state factions.

Close votes increased incentives to craft proposals that could attract marginal support rather than maximise one side’s preferences.

Logrolling is trading support across different issues: “I back your priority if you back mine.”

In constitution-making, it can assemble majority coalitions for a full governing framework when no single plan commands broad support on its own.

Founding compromises set long-lasting ground rules, so groups bargain more intensely over perceived permanent advantages.

Because changing constitutions is difficult, actors demand stronger safeguards before accepting outcomes they cannot easily reverse.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Identify two reasons why compromise was necessary at the Constitutional Convention.

1 mark for identifying any valid reason tied to conflicting interests (e.g., differences between large and small states, regional economic differences).

1 mark for identifying a second distinct valid reason (e.g., balancing effective national power with fear of tyranny; need to secure broad support for adoption).

(6 marks) Explain how the need to secure support from diverse states and interests shaped the Constitution’s design at the Constitutional Convention.

1 mark for explaining that delegates represented different state and regional interests that could not all be fully satisfied.

1 mark for explaining that compromise helped prevent deadlock or withdrawal from negotiations.

1 mark for explaining that compromise was used to balance stronger national capacity with protections against concentrated power.

1 mark for linking compromise to building legitimacy/acceptance (consent) for the new framework.

1 mark for describing that constitutional arrangements were negotiated as interconnected packages rather than isolated choices.

1 mark for overall coherence: a clear causal chain from diversity of interests → compromise → constitutional structure/acceptability.