AP Syllabus focus:

‘Exclusive power may be held by one level of government; national enumerated powers are written in the Constitution and define key areas of federal authority.’

Exclusive national powers are the Constitution’s most explicit grant of federal authority. Knowing where these powers are listed, what they cover, and why they matter clarifies how federalism allocates governing responsibilities in the United States.

Core idea: exclusive national powers and enumerated authority

Exclusive power can belong to only one level of government. For the national government, many exclusive powers are also enumerated—specifically written into the Constitution—so they are easier to identify and defend as constitutionally authorised.

Enumerated (delegated) powers: Powers expressly listed in the U.S. Constitution as granted to the national government, defining specific areas where the federal government may act.

Because these powers are written down, they help draw a boundary between what the federal government can do on its own authority and what remains outside its direct constitutional assignment.

Where enumerated national powers are found

Article I: Congress as the primary holder of enumerated powers

The largest concentration of enumerated national powers appears in Article I, Section 8, which lists what Congress may do. In federalism debates, these are central because they define core policy areas where the national government has constitutional permission to legislate.

Key enumerated areas include the power to:

Tax and spend for national purposes (raising revenue and allocating funds)

Borrow money on the credit of the United States

Regulate commerce with foreign nations and among the states (interstate commerce)

Establish rules of naturalisation (citizenship requirements) and bankruptcy laws

Coin money and regulate its value; punish counterfeiting

Establish post offices and post roads

Promote science and useful arts by securing copyrights and patents

Create federal courts inferior to the Supreme Court

Define and punish piracy and offences against the law of nations

Declare war, raise and support armies, provide and maintain a navy, and regulate the armed forces

Provide for organising and calling forth the militia under specified circumstances

Article II and Article IV: additional enumerated national authority

Although federalism discussions often highlight Congress, the Constitution also enumerates powers for other national institutions:

Historical chart-style “diagram of the federal government” that visually maps national institutions and their constitutional roles. It helps students connect the location of enumerated powers (e.g., Congress in Article I) to the broader constitutional system that also assigns responsibilities to the presidency and the courts. As a structured diagram, it supports quick recall of how federal authority is distributed across national institutions. Source

Article II enumerates presidential powers such as serving as commander in chief, making treaties (with Senate approval), and appointing key officers and judges (with Senate confirmation).

Article IV includes enumerated national responsibilities involving the states (for example, admitting new states), reinforcing that some state-related decisions are constitutionally assigned to the national level.

What makes a power “exclusive” at the national level

A national power is “exclusive” when the Constitution assigns it to the federal government in a way that leaves states without independent authority in that area. In practice, exclusivity is clearest when uniform national rules are necessary.

Commonly cited exclusive national areas include:

Foreign policy and national defence (e.g., declaring war, raising armies, maintaining a navy)

National economic uniformity tools (e.g., coining money)

Immigration and citizenship standards (e.g., naturalisation rules)

National communications infrastructure (e.g., post offices)

Exclusivity matters because it prevents a patchwork of state policies from undermining national security, national markets, or the United States’ ability to act as a single country internationally.

Why enumerated powers matter for AP Government analysis

They define “key areas of federal authority”

The syllabus emphasis is that national enumerated powers are written in the Constitution and define key areas of federal authority.

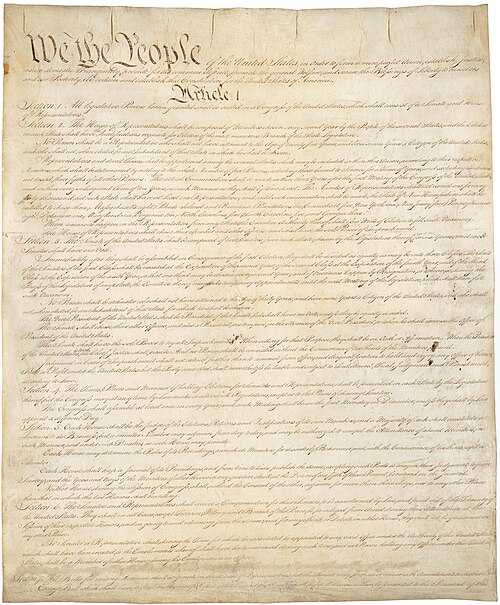

High-resolution facsimile of page 1 of the U.S. Constitution, showing the Preamble and the opening of Article I. Using the primary document helps anchor “enumerated powers” as text-based grants of authority rather than abstract concepts. It also supports close-reading skills often expected in AP Government constitutional analysis. Source

On the exam, this often means you should be able to:

Identify that a federal action is grounded in a specific constitutional listing (an enumerated power)

Explain how the listing supports national action in a particular policy area (taxation, war, currency, interstate commerce, etc.)

They structure arguments about constitutional legitimacy

Because enumerated powers are text-based, they are frequently used to justify (or challenge) federal laws and programs. A strong analytical move is to connect a policy area directly to the relevant enumerated power (for example, connecting national military policy to Congress’s war and armed forces powers).

They are a foundation for understanding the federal-state division of labour

Enumerated powers help explain why some issues are typically handled federally (national defence, currency) while other issues are not automatically federal responsibilities. In federalism, the written list is a starting point for describing what the national government is clearly empowered to do.

FAQ

Other branches have enumerated powers as well.

Examples include Article II powers of the President (such as commander in chief and making treaties with Senate consent) and Article III’s establishment of the Supreme Court’s judicial power.

Look for areas where the Constitution assigns authority to the federal government in a way that requires national uniformity.

Also look for clauses that explicitly restrict states from acting in that area (state prohibitions can signal exclusivity).

Frequently invoked areas include:

Taxing and spending (budgets, fiscal policy)

Interstate commerce (national market regulation)

War and armed forces (authorisations, military policy)

Naturalisation (citizenship standards)

Not always. Even when a power is enumerated, disagreements can arise about the scope of that power in a specific policy context.

Those disputes often turn on how broadly or narrowly the relevant constitutional language is read.

Enumeration reflects the Founders’ intent to create a national government with defined responsibilities.

A written list makes federal authority more transparent, supports accountability, and provides a textual basis for evaluating whether federal action fits within constitutionally assigned areas.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks) Define enumerated powers and identify one enumerated power of Congress.

1 mark: Defines enumerated powers as powers expressly listed in the Constitution and granted to the national government.

1 mark: Correctly identifies one congressional enumerated power (e.g., levy taxes, regulate interstate commerce, coin money, declare war).

Question 2 (6 marks) Explain how two enumerated powers of Congress define key areas of federal authority. In your answer, refer to the relevant constitutional location (for example, Article I, Section 8).

1 mark: Identifies a first enumerated power of Congress.

1 mark: Correctly links that power to a key area of federal authority (clear explanation of what it enables nationally).

1 mark: References an appropriate constitutional location for that power (e.g., Article I, Section 8).

1 mark: Identifies a second enumerated power of Congress.

1 mark: Correctly links that power to a different key area of federal authority (clear explanation).

1 mark: References an appropriate constitutional location for the second power (e.g., Article I, Section 8).