AP Syllabus focus:

‘Reserved powers are not delegated to the national government; they are reserved to the states and are affirmed by the Tenth Amendment.’

Reserved powers explain why states remain powerful in many everyday policy areas. The Tenth Amendment clarifies the Constitution’s division of authority by protecting state control over powers not granted to the national government.

Core Idea: Reserved Powers

Reserved powers are the foundation for state autonomy within the federal system: if the Constitution does not give a power to the national government (and does not deny it to the states), states generally keep it.

Reserved powers: Powers not delegated to the national government by the Constitution (and not prohibited to the states), therefore left to state governments.

Why They Matter

Reserved powers:

Preserve state sovereignty in a system where the national government has limited, listed authority.

Create policy diversity among states (different laws and standards across the country).

Shape political conflict when Congress or the president is perceived as intruding into traditional state domains.

The Tenth Amendment’s Role

The Tenth Amendment is the constitutional text most directly associated with reserved powers, reinforcing that the national government is not a government of unlimited authority.

A high-resolution historical reproduction of the Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution (including the Tenth Amendment). Using the original document format underscores that reserved powers are not just a concept in federalism—they are grounded in constitutional text adopted as part of the Bill of Rights. Source

Tenth Amendment: The constitutional amendment stating that powers not delegated to the United States nor prohibited to the states are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.

What the Amendment Affirms (and What It Does Not)

The Tenth Amendment primarily affirms a principle rather than providing a detailed list of state powers.

It supports the claim that the national government has enumerated (listed) powers, not general authority.

It does not automatically invalidate every federal action affecting states; disputes often depend on whether federal action can be tied to a constitutionally granted national power.

A key AP-level takeaway is the syllabus language itself: reserved powers are not delegated to the national government; they are reserved to the states and are affirmed by the Tenth Amendment.

Common Areas Where States Exercise Reserved Power

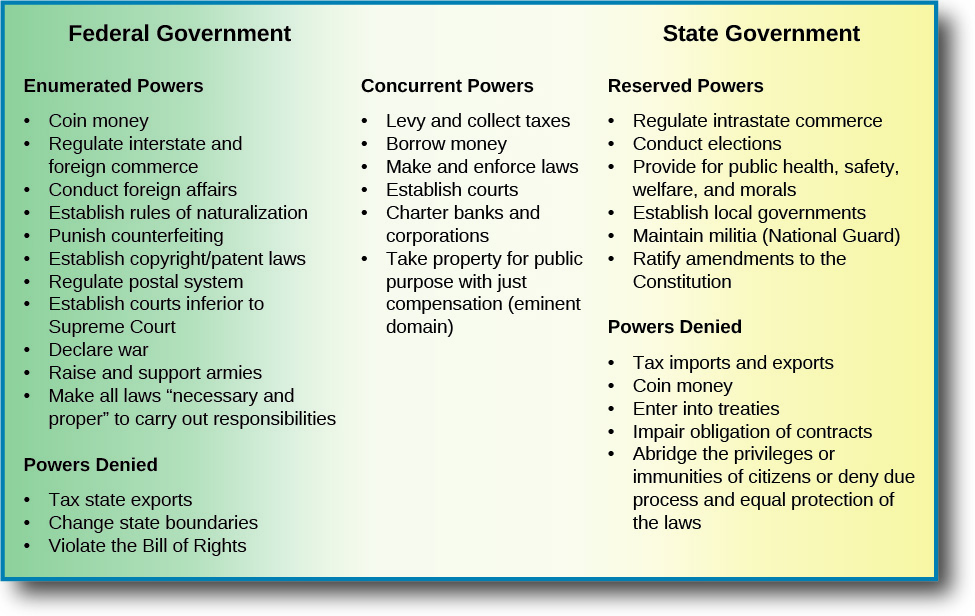

A three-column comparison chart showing how constitutional authority is divided among enumerated (federal), reserved (state), and concurrent (shared) powers, along with examples in each category. It reinforces the logic behind reserved powers: if a power is not granted to the national government, states retain broad governing authority in many domestic policy areas. Source

Because reserved powers concern what is not granted to the national government, they often appear in areas historically handled by state and local governments, such as:

Public health and safety rules (licensing, building standards, emergency measures)

Education policy (curriculum standards, school governance structures)

Criminal law and policing (most criminal codes, law enforcement organisation)

Elections administration (many voting procedures and districting choices, within constitutional limits)

Family and property law (marriage rules, inheritance, contracts—again, within constitutional constraints)

These categories illustrate the practical meaning of “reserved”: states are the default policymakers in many domestic areas unless the Constitution authorises national involvement.

Reserved Powers and “Powers … Reserved to the People”

The Tenth Amendment reserves powers to states or to the people, signalling that not all power is held by governments. In AP Gov terms, this connects to the broader constitutional idea that legitimacy flows from the people, and some freedoms and choices remain outside governmental reach unless lawfully regulated.

How Reserved Powers Create Intergovernmental Conflict

Reserved powers frequently become visible when:

A state argues a federal policy is beyond national authority.

The national government argues its policy is authorised by a granted power and therefore can affect states.

Typical fault lines include:

Regulatory boundaries: whether a federal rule is truly tied to a delegated national power.

State experimentation: states acting as “laboratories,” adopting different approaches that may clash with national preferences.

Enforcement and implementation: even when national policy is valid, states may resist its practical rollout, raising questions about the scope of state discretion.

What Students Should Be Able to Do

For this subtopic, focus on being able to:

Identify the concept: reserved powers = powers not delegated to the national government.

Link the concept to the text: the Tenth Amendment affirms reserved powers.

Explain the implication: states retain significant authority over many internal policy areas, and disputes arise when national action is seen as exceeding delegated power.

FAQ

No. It does not list powers.

It operates as a rule of interpretation: powers not given to the national government (and not forbidden to states) remain with states or the people.

It signals that not all authority rests with government.

Some decisions and freedoms remain individual unless government can justify regulation under a lawful power and within constitutional limits.

Yes.

If national action is grounded in a delegated constitutional power, it may influence state-regulated areas indirectly, which is why disputes focus on whether the federal government is acting within its granted authority.

It is a clear textual expression of limited national power.

Politicians and advocates use it to frame arguments about federal overreach, state autonomy, and the proper balance of authority.

Reserved powers allow states to adopt different rules and standards.

This can produce wide variation in services and rights depending on residence, and it can intensify conflict when national leaders seek uniformity.

Practice Questions

Explain what the Tenth Amendment indicates about powers not delegated to the national government.

1 mark: States that powers not delegated to the national government are reserved to the states (or the people).

1 mark: Uses the term reserved powers or accurately describes it.

1 mark: Links this to the principle that federal power is limited/constitutionally enumerated.

Describe reserved powers and analyse one way the Tenth Amendment can be used to support an argument for state authority in a federalism dispute.

1 mark: Defines reserved powers as powers not delegated to the national government.

1 mark: Identifies the Tenth Amendment as affirming reserved powers.

2 marks: Develops an argument explaining how the Tenth can support a state claim of authority (e.g., states retain default control in many domestic policy areas).

2 marks: Applies the argument to a federalism dispute in a general, accurate way (e.g., claims of federal overreach into traditional state policy domains), showing clear analytical linkage.