AP Syllabus focus:

‘The Columbian Exchange introduced American crops to Europe, contributing to European population growth after 1492.’

The transfer of New World crops to Europe after 1492 reshaped European diets, boosted agricultural productivity, and dramatically increased population growth by supplying calorie-dense, reliable food sources.

New World Crops and Europe’s Population Growth

The Columbian Exchange initiated a massive transatlantic transfer of plants, animals, people, and pathogens. Within this broad transformation, the movement of American staple crops such as maize, potatoes, and cassava played a central role in altering European nutrition and demographic patterns. These crops provided more calories per acre than many traditional European grains, helping societies recover from recurring food shortages and enabling sustained population expansion. Understanding this agricultural shift illuminates how transatlantic contact reshaped European life in profound and lasting ways.

The Columbian Exchange as an Agricultural Turning Point

The Columbian Exchange created an unprecedented botanical transfer.

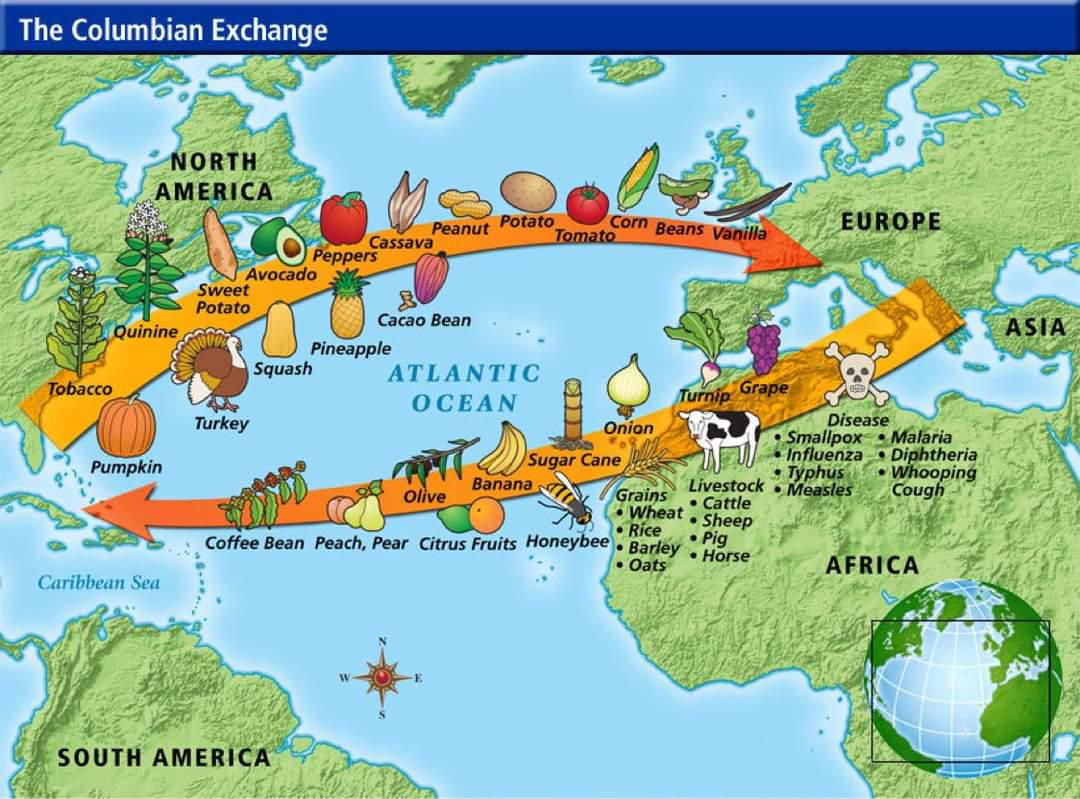

This map illustrates the Columbian Exchange as arrows carrying crops, animals, and diseases between the Americas and the Old World. Note how calorie-rich American foods such as potatoes, maize (corn), and cassava move toward Europe and Africa, providing the agricultural basis for long-term population growth. The image also includes animals and epidemic diseases, which extend beyond the crop-focused AP requirement but help contextualize the broader Atlantic transformations. Source.

Although Europeans introduced wheat, barley, sugarcane, and Old World domesticated animals to the Americas, it was the flow of New World crops to Europe that generated some of the most significant long-term demographic consequences. These new foods were not immediately embraced everywhere, but as familiarity grew, they became essential to European agricultural systems.

High-Calorie Crops and Their European Adoption

The most influential crops introduced to Europe included:

Potatoes: Highly nutritious, able to thrive in poor soils, and resistant to short-term climate variations.

Maize (corn): Adaptable to diverse climates, flexible in its uses, and easily integrated into existing farming rhythms.

Tomatoes, peppers, and pumpkins: Less central to caloric intake but culturally transformative and eventually incorporated into regional cuisines.

Because these crops supported more people with less land, agricultural communities gradually integrated them into their crop rotations and subsistence practices.

Why Potatoes Became a Demographic Engine

The potato had an especially far-reaching demographic impact. When introduced into European fields, potatoes produced significantly higher caloric yields compared to rye or wheat. They also stored well and were less vulnerable to freezing temperatures or episodic droughts.

Caloric Yield: The total number of calories produced per unit of land cultivated, reflecting a crop’s efficiency in supporting population growth.

As potatoes became common in household gardens and rural farms, European families could maintain more stable diets throughout the year. This change reduced mortality related to famine and malnutrition, especially in Northern and Eastern Europe, where traditional grains often failed in cold or wet seasons.

One important sentence explaining demographic change: food security fostered higher survival rates, earlier marriages, and increased family sizes as European peasants gained confidence that they could feed more children.

Maize and Regional Agricultural Shifts

While potatoes reshaped northern diets, maize became central to southern and eastern European agriculture. Farmers valued maize because:

It grew well in warmer climates.

It required fewer labor-intensive practices than some traditional grains.

It could be consumed directly or fed to livestock, increasing protein availability.

Maize did not replace wheat entirely, but it supplemented existing food staples, reducing the frequency of grain shortages and stabilizing regional markets.

Linking New Crops to Population Growth

The introduction of calorie-dense crops encouraged population growth through several connected mechanisms:

Improved nutrition increased survival rates among infants and children.

More reliable harvests reduced the cyclical famines that plagued pre-modern Europe.

Greater food security allowed families to have more children with fewer fears of starvation.

Enhanced agricultural productivity freed some laborers for urban work, contributing indirectly to economic expansion.

In this way, the agricultural consequences of the Columbian Exchange triggered significant social and demographic change, helping Europe move toward the conditions that facilitated later industrial development.

Broader Social and Economic Effects

As the European population expanded, demand for goods, labor, and land also increased. Larger populations stimulated domestic and international trade networks, creating new opportunities for merchants and farmers. In turn, European governments viewed population growth as a source of military and economic strength, reinforcing the importance of maintaining stable food supplies.

Cultural Adjustments and Dietary Transformation

Although Europeans initially resisted unfamiliar foods—especially potatoes, which some viewed with suspicion because they were not mentioned in the Bible—these crops eventually became central features of regional cuisines. For example:

Potatoes became staples in Ireland, Scotland, Prussia, and Russia.

Maize became fundamental in parts of Italy, the Balkans, and the Iberian Peninsula.

Tomatoes and peppers reshaped Mediterranean cooking, influencing dishes from Spain to Italy.

These cultural shifts were gradual but enduring, demonstrating how the Columbian Exchange altered not just diets but also identities and regional culinary traditions.

The Long-Term Legacy in European Society

By making famine less frequent and food more abundant, New World crops contributed to Europe’s steady demographic growth from the sixteenth century onward.

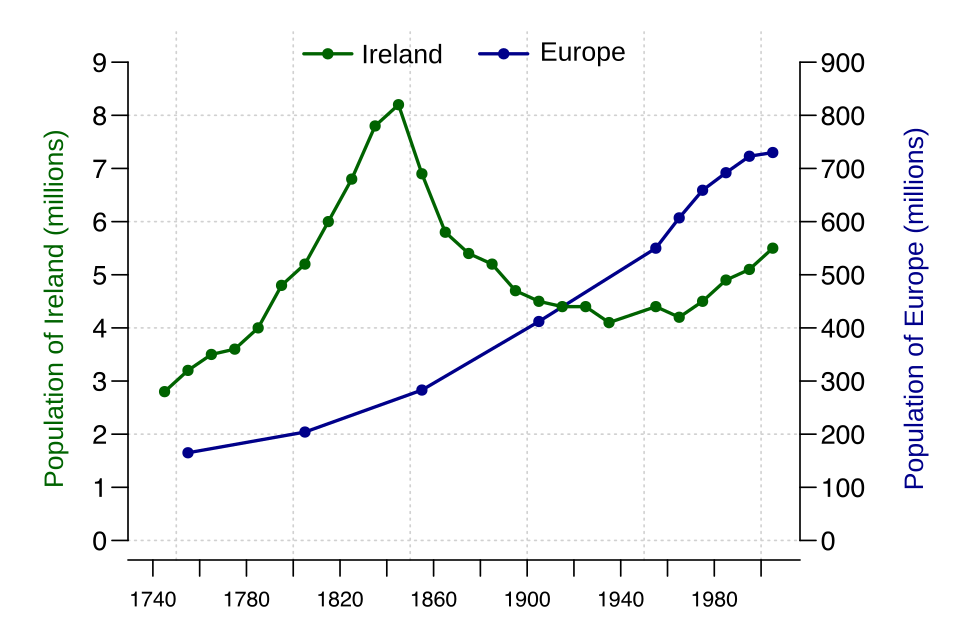

This graph tracks indexed population growth in Europe and in Ireland from 1750 to the early twenty-first century. It highlights how European population climbed steadily in the centuries after the Columbian Exchange, when crops like the potato became central to food security. The focus on Ireland and the dramatic nineteenth-century decline tied to the Great Famine extends beyond the AP period but illustrates the risks of dependence on a single New World crop. Source.

While disease decline, improved sanitation, and economic development also played roles, enhanced agricultural productivity provided by American crops formed one of the earliest foundations for Europe’s population surge.

The steady reliance on American crops illustrates the transformative power of ecological exchange. The Columbian Exchange was not merely an event of exploration and conquest—it was a fundamental biological and social shift that redefined European life through the introduction of highly productive New World foods.

FAQ

Adoption varied significantly across regions. Some areas welcomed new crops within decades, especially where traditional grains were unreliable. Others resisted them for cultural, religious, or agricultural reasons.

For example, potatoes spread slowly in France due to suspicion that they caused illness, while in Ireland they became central within a century because they thrived in poor soils.

Overall, widespread adoption unfolded gradually between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries.

Many New World crops, particularly potatoes and maize, could grow successfully in marginal lands where wheat or rye struggled.

These crops:

• Required fewer inputs

• Withstood colder temperatures or episodic drought

• Offered higher calorie returns even in poor soil conditions

This made them agricultural stabilisers in regions historically vulnerable to harvest failure.

Yes. Maize and certain legumes from the Americas provided new feed options, supporting increased livestock numbers.

Greater availability of feed helped:

• Expand dairy production

• Improve winter survival rates for animals

• Increase the availability of meat and animal-based fertilisers

This indirectly boosted agricultural productivity and nutrition.

A more reliable food supply supported sustained population growth, which in turn created pressure for land, labour, and employment diversification.

As rural families expanded, surplus population migrated into towns, where demand for crafts, trade, and wage labour grew. This contributed to the gradual strengthening of early modern European urban centres.

Yes, though less dramatic than the ecological effects in the Americas. New crops altered soil use, crop rotations, and local biodiversity.

In some regions:

• Maize and potatoes displaced older grain varieties

• New planting cycles changed soil nutrient patterns

• Increased land under cultivation led to greater deforestation

These ecological shifts unfolded steadily over several centuries.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the introduction of New World crops contributed to population growth in Europe after 1492.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark:

• Identifies a valid effect (for example, improved nutrition or increased food supply).

2 marks:

• Gives a clear explanation of how a specific New World crop, such as the potato or maize, contributed to population growth.

3 marks:

• Provides a developed explanation that links the introduction of the crop to wider demographic outcomes, such as reduced famine, better survival rates, or earlier marriages and larger families.

(4–6 marks)

Analyse the extent to which the transfer of New World crops to Europe reshaped European societies between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. In your answer, consider both demographic and economic effects.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks:

• Describes at least one demographic effect and one economic effect of New World crops on Europe, with accurate factual detail.

5 marks:

• Shows clear analysis of how these effects reshaped European societies, making explicit connections between improved agricultural productivity, population expansion, and social or economic change.

6 marks:

• Presents a well-structured argument evaluating the extent of change, supported by specific examples (for example, the role of potatoes in Northern Europe or maize in Southern Europe), and demonstrates understanding of both the benefits and limitations of these developments.