AP Syllabus focus:

‘Spanish conquest was aided by deadly epidemics and by introducing crops and animals previously unknown in the Americas.’

Spanish arrival in the Americas triggered profound demographic, environmental, and cultural transformations as epidemics, conquest, and ecological change reshaped Indigenous societies and enabled Spanish imperial expansion.

The Foundations of Spanish Conquest

Spanish conquest in the sixteenth century relied on a combination of strategic alliances, military technology, and the introduction of new pathogens and species. While Spanish soldiers were few in number, their actions unfolded within a broader system of global exchange and biological transformation that reshaped power dynamics across the Americas.

Military Technology and Tactical Advantages

Spanish conquistadors leveraged steel weaponry, horses, and gunpowder-based firearms, technologies previously unknown in the Americas. Horses in particular provided a critical psychological and tactical advantage. Their speed and maneuverability created shock on the battlefield and helped Spanish forces conduct reconnaissance across unfamiliar terrain.

Indigenous Alliances and Local Rivalries

The Spanish capitalized on preexisting conflicts among Indigenous polities. Groups such as the Tlaxcalans allied with the Spanish against rival powers like the Mexica. These alliances supplied manpower, logistical support, and invaluable geographical knowledge, enabling the Spanish to project influence far beyond what their small expeditionary forces could achieve independently.

This seventeenth-century painting depicts Hernán Cortés and Moctezuma II confronting each other amid Spanish soldiers and Aztec nobles. It visually conveys the political tensions and unequal power dynamics preceding alliance-building and conquest. The image includes artistic details beyond the syllabus scope, but these elements help illustrate the significance of early diplomatic encounters. Source.

Epidemics and Demographic Catastrophe

The most devastating factor enabling Spanish conquest was the unintentional introduction of Old World diseases. These pathogens, long endemic in Europe, had no historical presence in the Americas, leaving Indigenous populations without immunological defenses.

Smallpox and Mortality

Smallpox, introduced early in contact, spread rapidly along trade routes and social networks. The disease caused high fever, pustular eruptions, and exceptionally high mortality rates among Indigenous peoples.

Immunological immunity: The body’s acquired ability to recognize and defend against pathogens due to long-term exposure or inherited resistance.

The demographic consequences were catastrophic. In many regions, mortality rates exceeded 50–90%, undermining Indigenous social structures and destroying the political stability of empires such as the Aztec and Inca.

Spanish forces often arrived in cities already weakened by disease, accelerating imperial collapse and enabling military victories that would otherwise have been impossible.

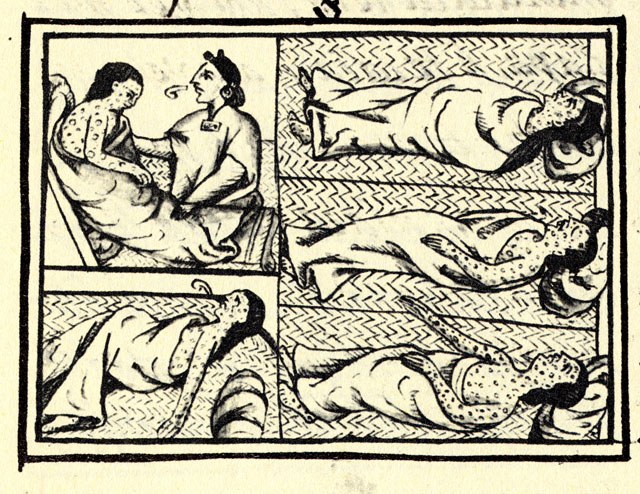

This manuscript illustration shows Nahua individuals suffering from smallpox, lying on mats and covered in pustules. Created by Indigenous artists, it documents the devastating human toll of epidemic disease during the Spanish conquest. The visual detail exceeds syllabus requirements but deepens understanding of the demographic collapse described in the notes. Source.

Ecological Change and the Columbian Exchange

Spanish conquest initiated far-reaching ecological change, linking the Eastern and Western Hemispheres in what historians call the Columbian Exchange.

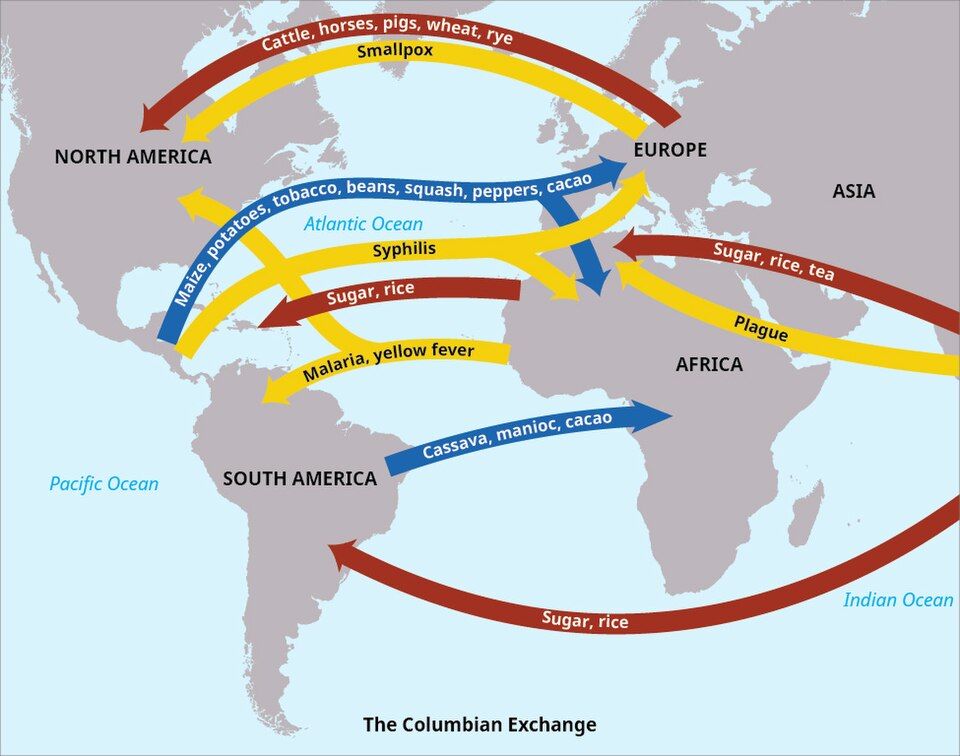

This map depicts major biological exchanges between the Old and New Worlds, including the transfer of horses, cattle, pigs, wheat, and smallpox into the Americas. It visually reinforces the ecological and economic transformations outlined in the notes. The map includes additional exchanged items not listed in the syllabus, but they remain closely connected to the core concept of the Columbian Exchange. Source.

Introduction of Domesticated Animals

The Spanish introduced domesticated animals unknown in the Americas, including:

Horses, which reshaped transportation and labor systems

Cattle, which altered landscapes through grazing

Pigs, which reproduced rapidly and disrupted Indigenous agriculture

Sheep, which encouraged wool production and changed vegetation patterns

These animals often damaged Indigenous fields and contributed to soil depletion, fundamentally altering local ecosystems. Some groups later integrated horses into their own cultures, especially on the Great Plains, but initial impacts were destabilizing.

New Crops and Agricultural Shifts

Spanish conquerors also introduced Old World crops that restructured agricultural production in the colonies:

Wheat, which became a staple in colonial diets

Sugarcane, which required intensive labor and fueled plantation systems

Bananas and citrus fruits, which were grafted onto Caribbean and mainland landscapes

These crops enabled the establishment of export-oriented plantation economies, altering land use and increasing the demand for coerced labor from Indigenous peoples and, later, enslaved Africans.

Environmental and Social Consequences of Conquest

The combination of epidemics, livestock introduction, and new agricultural models reshaped Indigenous environments and social systems.

Land Use Transformation

Spanish settlers reorganized landholdings through systems such as encomienda, redistributing Indigenous land to Spanish elites. Livestock grazing often caused erosion and deforestation, while introduced crops demanded irrigation, terracing, and new labor practices.

Cultural and Religious Impacts

As populations dwindled and communities fragmented, Indigenous religious practices, gender roles, and political authority faced substantial disruption. Missionaries often attributed epidemics to spiritual causes, using disease as justification for conversion efforts.

Processes Driving Ecological Reordering

Several interlocking processes accelerated ecological change:

Biological Invasion: Introduction of microorganisms, plant seeds, and animal species

Labor Reorganization: Forced labor in agriculture and mining reshaped settlement patterns

Commercial Agriculture: Sugar, wheat, and livestock production increased land consolidation

Urban Growth: Colonial cities created new markets and altered surrounding ecosystems

These processes combined to reorient local economies toward Spanish imperial demands.

Spanish Advantage Through Catastrophic Change

The synergy between conquest, disease, and ecological transformation explains why Spanish colonizers gained control over vast territories. Epidemics destabilized Indigenous societies, introduced species reshaped environments, and colonial institutions redirected labor and resources toward Spanish priorities. This series of interrelated developments formed the foundation for early Spanish imperial dominance in the Americas.

FAQ

Many Indigenous communities initially applied traditional remedies, such as herbal treatments, steam baths, or ritual healing, because they had no prior experience with Old World pathogens.

However, these methods often proved ineffective against smallpox and measles, leading to spiritual crises when long-trusted healers could not stop the devastation.

Some groups incorporated certain European medical practices later on, though often selectively and alongside Indigenous frameworks of health and spirituality.

Pigs reproduced rapidly, needed little supervision, and frequently escaped into forests or farms, becoming invasive.

They rooted up crops, disturbed soil, and damaged Indigenous fields, forcing communities to adapt food production strategies.

In some regions, conflicts arose when Indigenous people killed roaming pigs, prompting Spanish settlers to accuse them of property damage and demand compensation.

In many agricultural societies, women were responsible for maize cultivation and controlled much of local food production.

When Old World crops and livestock disrupted traditional farming patterns, women’s economic roles sometimes diminished as men took on ranching or labour tied to colonial systems.

In other areas, women continued to maintain key agricultural tasks, but the restructuring of land use and labour demands often reduced their political influence.

Responses varied widely, but common strategies included:

• Relocating fields to avoid grazing animals

• Building barriers or using landscape features to limit livestock intrusion

• Negotiating agreements with local Spanish authorities

• Integrating select European crops into Indigenous agricultural cycles

These adaptations could reduce damage but rarely prevented long-term ecological transformation.

The combination of disease, forced labour, and the spread of European livestock often made traditional village locations unsustainable.

Some communities moved to less contested territories, while others were relocated forcibly under Spanish policies that concentrated labour near missions, mines, or estates.

These shifts frequently disrupted trade networks, kinship ties, and cultural practices tied to ancestral homelands, accelerating broader social upheaval.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which epidemic disease contributed to the success of the Spanish conquest in the early sixteenth century.

(1–3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks for:

1 mark for identifying a valid impact of epidemic disease (e.g., smallpox weakened Indigenous populations).

1 mark for describing how this impact affected Indigenous political, military, or social structures (e.g., high mortality destabilised leadership).

1 mark for explaining how this facilitated Spanish conquest (e.g., Spaniards encountered cities already devastated, enabling easier military victories).

(4–6 marks)

Assess the impact of ecological changes brought about by the Spanish conquest on Indigenous societies in the Americas between 1492 and 1600.

(4–6 marks)

Award up to 6 marks for:

1–2 marks for identifying ecological changes introduced by the Spanish (e.g., introduction of horses, cattle, wheat, and sugarcane).

1–2 marks for explaining the effects of these changes on Indigenous societies (e.g., livestock damaged fields, altering land use; new crops changed subsistence patterns).

1–2 marks for analysing the broader consequences for Indigenous communities (e.g., reorganisation of labour systems, environmental degradation, disruption of cultural practices).