AP Syllabus focus:

'Explanation on how to determine the critical value (z*) corresponding to the chosen confidence level, utilizing the standard normal distribution. This value is crucial in calculating the margin of error and, subsequently, the confidence interval.'

In this section, you learn how a chosen confidence level leads to a specific critical value, linking probability ideas to practical confidence interval construction methods.

Determining the Critical Value

When constructing a confidence interval for a population proportion, the critical value is the specific multiplier that stretches the margin of error to match your chosen confidence level. It connects the desired reliability of the interval to the variability described by the standard normal distribution.

Critical value: A positive number, usually denoted z*, taken from the standard normal distribution that corresponds to a chosen confidence level and is used to compute the margin of error.

Because the critical value comes from a probability model rather than your particular dataset, it depends only on the confidence level and the assumption of an approximately normal sampling distribution, not on the sample itself.

When you select a confidence level, you are choosing what proportion of intervals, in repeated sampling, you want to capture the true population proportion.

Confidence level: The long-run percentage of confidence intervals, constructed in the same way from repeated random samples, that will contain the true population parameter.

The higher the confidence level you demand, the larger the critical value must be, which in turn makes the interval wider.

The Standard Normal Distribution and z-Scores

To determine the critical value, AP Statistics uses the standard normal distribution, a bell-shaped curve with mean 0 and standard deviation 1, measured in z-scores.

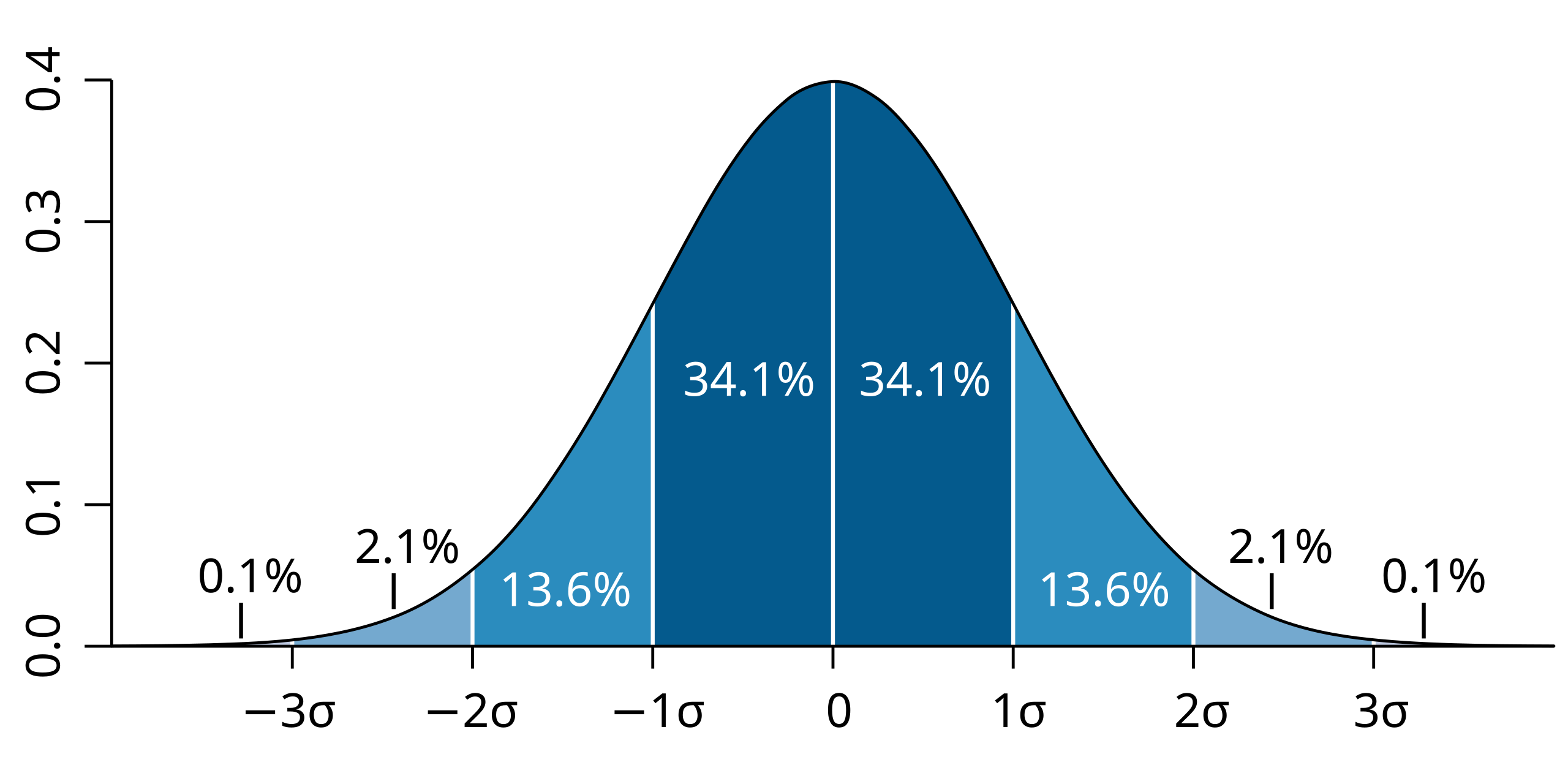

A standard normal distribution centered at 0, with each standard deviation highlighted and labeled. The shaded percentages show how much area falls within 1, 2, and 3 standard deviations of the mean. The additional numerical labels exceed the strict syllabus requirements but help illustrate how z-scores correspond to probability. Source.

A z-score tells you how many standard deviations an observation is above or below the mean. For confidence intervals, the critical value z* is a z-score that cuts off the appropriate central area under this curve.

Standard normal distribution: A normal distribution with mean 0 and standard deviation 1, used as a reference model for standardized z-scores.

The standard normal distribution is symmetric about 0, so the central area between −z* and +z* equals the chosen confidence level, while the remaining area is split equally between the two tails.

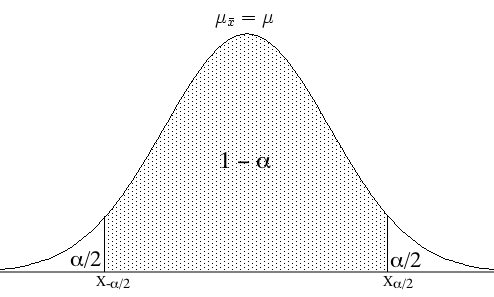

A normal curve with the central probability region shaded and the endpoints labeled by the critical values. The diagram shows how confidence levels correspond to central areas and tail probabilities. The α and z_{α/2} notation slightly extends beyond the syllabus wording but matches AP Statistics conventions. Source.

Linking Confidence Level to the Critical Value

To find the critical value for a particular confidence level:

The central area between −z* and +z* should equal the confidence level (for example, 0.95 for 95% confidence).

The tail area outside the interval is 1 − confidence level.

Because of symmetry, each tail has area (1 − confidence level) ÷ 2.

This relationship allows you to map confidence levels to standard critical values.

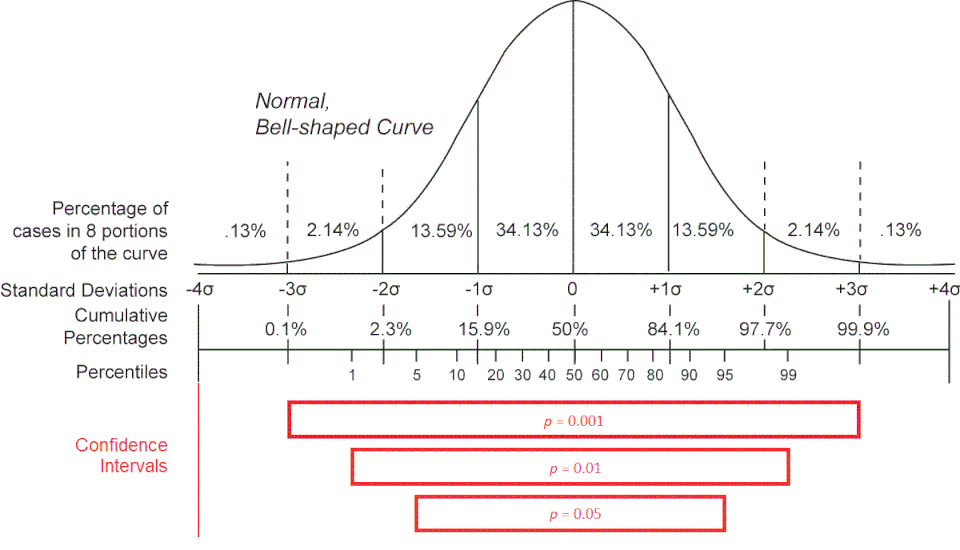

A sequence of normal curves displaying central intervals of various widths, each corresponding to a different confidence level. Wider intervals represent higher confidence levels and larger critical values. Some probability labels use p-notation not explicitly required by the syllabus but consistent with general interval theory. Source.

Common examples for two-sided confidence intervals for a proportion include:

90% confidence: z* is approximately 1.645

95% confidence: z* is approximately 1.96

99% confidence: z* is approximately 2.575

These values come from standard normal tables or technology and are treated as known constants at the AP level.

Practical Procedure for Determining z*

In practice, determining the critical value involves a consistent set of steps:

Specify the confidence level (for example, 90%, 95%, or 99%) based on the context of the problem and how much certainty is desired.

Convert the confidence level to a central probability between −z* and +z* on the standard normal curve.

Compute the tail area as 1 minus the central probability, then divide by 2 to find the area in each tail.

Use a z-table or technology (such as a calculator’s inverse normal function) to find the z-score with cumulative area equal to the left-tail probability.

Take the positive z-score as the critical value z* for the two-sided confidence interval.

Because the distribution is symmetric, you only need the positive z* when constructing intervals; the negative counterpart simply marks the lower bound on the other side of the mean.

Using the Critical Value in Margin of Error and Confidence Intervals

Once you know z*, you can use it to determine the margin of error and then the full confidence interval for a population proportion. The margin of error is the product of the critical value and the standard error of the sample proportion.

EQUATION

= Sample proportion (no units)

= Critical value from the standard normal distribution for the chosen confidence level (no units)

= Sample size (number of observations in the sample)

Here, z* directly controls how far the interval extends from the sample proportion. A larger z* produces a larger margin of error and therefore a wider interval, while a smaller z* produces a narrower interval.

Choosing an Appropriate Confidence Level (and Thus z*)

Selecting a confidence level is a modeling decision that determines the critical value you will use. Important considerations include:

Required certainty: Situations with serious consequences for incorrect conclusions often justify higher confidence levels, which produce larger z* values.

Desired precision: Higher confidence (larger z*) increases interval width, reducing precision. Lower confidence narrows the interval but reduces the long-run capture rate of the true parameter.

Feasibility of larger samples: If the sample size cannot be increased, the only way to reduce interval width is to choose a lower confidence level, which corresponds to a smaller z*.

In every case, determining the critical value means translating the verbal demand for a certain level of confidence into a precise numerical multiplier taken from the standard normal distribution, ready to be used in the margin of error and confidence interval formulas.

FAQ

Confidence levels are linked to the area under the standard normal curve because confidence intervals rely on the long-run behaviour of repeated sampling. The central area reflects the proportion of intervals expected to capture the true parameter.

These areas are fixed properties of the normal distribution, meaning each confidence level always corresponds to the same cut-points. For example, the symmetry of the curve ensures the tail areas are equal on both sides, allowing consistent determination of critical values.

AP Statistics typically accepts standard rounded values, such as 1.645, 1.96, or 2.575, because the impact of minor rounding differences on margins of error is negligible at this level.

Calculators and statistical tables may provide more precise values, but students are not expected to memorise extended decimals. Consistency is more important than extreme precision.

The sample data do not directly determine z* because the critical value comes solely from the chosen confidence level.

However, the sampling distribution must be approximately normal for z* to be valid. This depends on conditions such as sufficiently large expected counts, not on the actual shape of the collected data.

A higher confidence level requires capturing a larger proportion of the normal curve, meaning a bigger multiplier is needed.

Even with a very large sample size, the critical value increases with confidence level. Although sampling variability decreases as n grows, the effect of the larger multiplier remains.

One-sided confidence bounds use different tail areas because all the excluded probability falls on one side of the distribution.

For a one-sided interval:

• The confidence level equals the area to the left or right of the critical value.

• The critical value is larger than the two-sided equivalent for the same nominal confidence level because the entire tail probability is concentrated on one side.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A researcher plans to construct a 95% confidence interval for a population proportion.

State the critical value z* that should be used and explain what this value represents in the context of the standard normal distribution.

Question 1

Total: 3 marks

• 1 mark for stating that the critical value for a 95% confidence interval is approximately 1.96.

• 1 mark for stating that this value corresponds to the z-score capturing the central 95% of the standard normal distribution.

• 1 mark for explaining that the remaining 5% is split equally into the two tails of the distribution.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A wildlife organisation is estimating the proportion of local residents who support creating a new conservation area. They plan to construct a 90% confidence interval for the true population proportion.

(a) Explain how the critical value z* for a 90% confidence interval is determined using the standard normal distribution.

(b) Describe how the chosen confidence level affects the size of the critical value and the resulting margin of error.

Question 2

Total: 6 marks

(a)

• 1 mark for stating that the central area of the standard normal distribution must equal 90%.

• 1 mark for recognising that the remaining 10% is split into two tails of 5% each.

• 1 mark for identifying that the z-score with 5% in the left tail (or 95% cumulative probability) gives the value of z*.

(b)

• 1 mark for stating that higher confidence levels require larger critical values.

• 1 mark for noting that larger critical values produce a larger margin of error and therefore a wider confidence interval.

• 1 mark for stating that lower confidence levels result in smaller critical values and narrower confidence intervals.