AP Syllabus focus:

‘Step-by-step guide on constructing the confidence interval for the population proportion, p-hat ± (z* * sqrt[(p-hat(1-p-hat))/n]), integrating the concepts of point estimate, margin of error, and critical value to estimate the range in which the true population proportion likely falls.’

Constructing a confidence interval for a population proportion provides a structured method to estimate an unknown population value using sample data, combining point estimates with measures of sampling uncertainty.

Constructing a Confidence Interval for a Population Proportion

Constructing a confidence interval for a population proportion involves combining three essential components: the point estimate, the critical value, and the standard error to produce a range of plausible values for the true population proportion. This process aligns directly with the syllabus requirement to apply the formula and emphasizes the conceptual meaning behind each part of the interval.

Understanding the Components of the Confidence Interval

The confidence interval is built on the sample proportion , which serves as the best estimate of the population proportion. To account for sampling variability, the construction incorporates a margin of error, combining the variability measure (standard error) with the confidence-level–dependent critical value.

Point Estimate: The sample statistic used to estimate a population parameter; here, the point estimate is the sample proportion .

Using the point estimate alone is insufficient because sample data naturally vary from sample to sample. Therefore, constructing the entire interval provides a fuller picture of uncertainty in the estimate.

Identifying What the Formula Represents

The confidence interval formula uses the standard error of to quantify expected sampling variability and the critical value to scale that variability according to the chosen confidence level.

EQUATION

= Sample proportion (unitless)

= Critical value from the standard normal distribution (unitless)

= Sample size (number of observations)

This formulation integrates all major ideas required for constructing the interval: the central estimate, its variability, and the multiplier that adjusts for the desired level of confidence.

A critical sentence explaining these components connects the formula to the logic of statistical inference.

Steps for Constructing the Confidence Interval

To ensure clarity and accuracy, constructing a confidence interval for a population proportion typically follows a structured sequence. Each step relies on the previous one, reinforcing the importance of conceptual understanding and procedural correctness.

Follow this process:

Identify the point estimate ().

Compute using the number of successes divided by the sample size.

Check that conditions are met.

Independence and normality conditions must be verified before using the interval formula, though these checks are addressed in earlier subsubtopics.

Calculate the standard error using the formula .

Determine the critical value ().

This corresponds to the chosen confidence level (e.g., 1.96 for 95%).

Compute the margin of error by multiplying and the standard error.

Construct the confidence interval using .

Interpret the interval in context, focusing on what the range suggests about the population proportion.

Written in words, a confidence interval has the form point estimate ± margin of error.

A visual representation of a confidence interval on a normal curve, with LL and UL marking the lower and upper bounds. The shaded region represents all plausible values for the parameter at the chosen confidence level, while the tails show unlikely values. Although generic, the structure directly parallels the one-sample z-interval for a population proportion. Source.

The Role of Each Component

Each part of the confidence interval formula contributes uniquely to understanding the likely location of the population proportion:

The point estimate anchors the interval in observed data.

The standard error expresses sampling variability, becoming smaller as sample size increases.

The critical value expands or contracts the interval depending on the desired confidence level.

The margin of error combines standard error and critical value to reflect the total uncertainty.

Margin of Error: The amount added to and subtracted from the point estimate to create the interval, representing expected sampling variation scaled by confidence level.

This explanation clarifies how the interval balances the precision of the estimate with the uncertainty inherent in sampling.

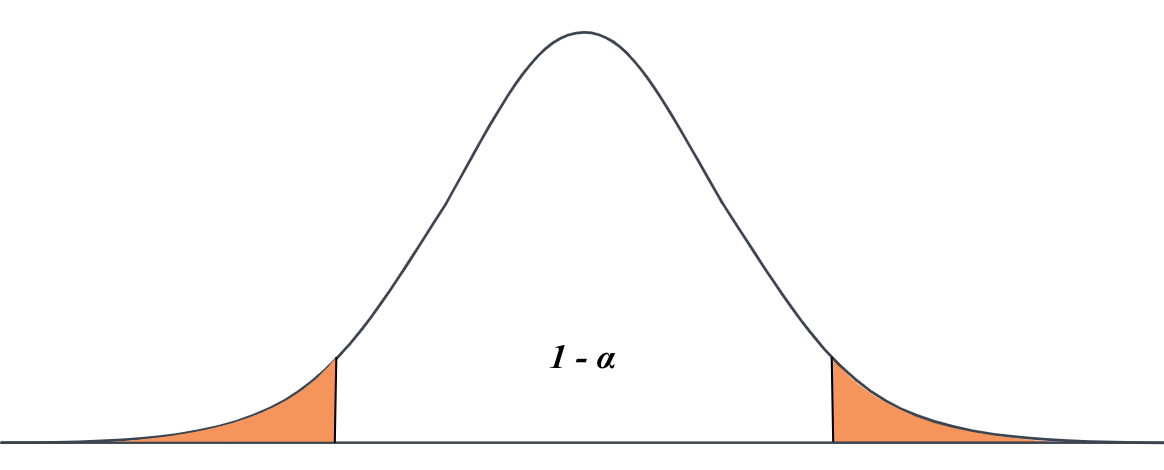

The critical value z* comes from the standard normal distribution and cuts off the middle C% of the area, leaving α/2 in each tail.

A standard normal curve showing how the critical values ±z* define the middle (1−α)100% of the distribution. The shaded region represents the confidence level, while the unshaded tails represent the remaining α. This geometry underlies the selection of z* for the one-sample z-interval for a population proportion. Source.

Why Constructing the Interval Matters

Constructing a confidence interval allows statisticians to express uncertainty using a quantitative range rather than a single point estimate. The interval communicates both the sample result and the degree of confidence that the method will capture the true population proportion in repeated sampling.

The procedure is valuable because:

It provides an interpretable range for the unknown population parameter.

It accounts for the variability expected in different random samples.

It incorporates the analyst’s chosen confidence level, reflecting how cautious they wish to be.

Bringing the Components Together

The constructed interval presents a balance of empirical evidence and theoretical justification. By integrating the components—point estimate, margin of error, and critical value—the method produces an interval that quantifies uncertainty and frames inference in terms of probability and sampling behavior.

FAQ

The interval is centred on the sample proportion because it is the unbiased estimator of the population proportion. This means, on average across many samples, the sample proportion equals the true proportion.

Placing the interval around any adjusted value would distort the interpretation of the method, as the purpose of a confidence interval is to reflect sampling variation rather than impose corrections unless required for more advanced methods.

When p-hat is close to 0 or 1, the interval may become noticeably asymmetric if computed using more advanced methods, but the standard z-interval still remains symmetric because it uses the normal approximation.

In these cases, the normal approximation may perform poorly, so the interval may be less reliable unless the sample size is large enough to counteract the imbalance.

Very high confidence levels, such as 99.9%, produce extremely wide intervals. This reduces the usefulness of the estimate because the range becomes too large to be practically meaningful.

While these intervals are statistically valid, a balance between precision and confidence is typically preferred. In practice, 90%, 95%, and 99% are most commonly used because they maintain interpretability.

Increasing the sample size reduces the standard error, but the rate of reduction slows as the sample becomes large. Doubling an already large sample does not halve the width of the interval.

Because standard error decreases with the square root of n, large increases in sample size are required to achieve modest improvements in interval precision.

Differences in sample proportions lead to changes in the standard error, which directly affects the margin of error. Even if sample sizes match, a sample proportion closer to 0.5 will produce a larger standard error.

Additionally:

• Variability in sampling methods

• Differences in data quality or independence

• Random fluctuations in observed outcomes

All can influence the width of the resulting interval.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A researcher surveys a random sample of 180 customers and finds that 63 of them prefer a new product design.

(a) Identify the point estimate needed to construct a confidence interval for the population proportion.

(b) State the formula structure used to construct a confidence interval for a population proportion.

Question 1

(a)

• 1 mark: Correctly identifies the point estimate as the sample proportion (63 out of 180, or 0.35).

(Any equivalent form, such as 63/180, earns the mark.)

(b)

• 1 mark: States the structure of the confidence interval as “point estimate ± margin of error” or “p-hat ± (z* × standard error)”.

• Partial credit (0.5 marks if used): Any clearly recognisable version of the formula.

Total: 2 marks

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A school administrator wants to estimate the proportion of students who regularly complete their homework. She selects a random sample of 220 students and finds that 171 report completing their homework regularly.

(a) Calculate the sample proportion.

(b) Describe the components required to construct a confidence interval for the population proportion.

(c) Explain why verifying the normality condition is necessary before constructing the interval.

Question 2

(a)

• 1 mark: Correctly calculates the sample proportion as 171/220 or 0.777 (accept rounding to three decimal places).

(b)

Up to 3 marks:

• 1 mark: States the point estimate (sample proportion).

• 1 mark: Mentions the standard error as the measure of variability.

• 1 mark: Identifies the critical value (z*) as based on the chosen confidence level.

(Award full marks only if all three components are clearly described.)

(c)

Up to 2 marks:

• 1 mark: Explains that the sampling distribution of the sample proportion must be approximately normal.

• 1 mark: States that this is checked by ensuring expected successes and failures (np-hat and n(1 – p-hat)) are sufficiently large.

(Any equivalent phrasing earns the marks.)

Total: 6 marks