AQA Specification focus:

‘Cyclical and structural budget deficits and surpluses.’

Budget deficits occur when government spending exceeds revenue, but not all deficits are alike. Understanding cyclical and structural deficits is essential for A-Level Economics.

Understanding Budget Deficits and Surpluses

A budget deficit arises when government spending exceeds tax revenues in a given period, while a budget surplus occurs when revenues exceed spending. Both concepts are central to fiscal policy analysis and have significant implications for the economy. The AQA specification emphasises the need to distinguish between cyclical and structural deficits and surpluses.

Budget Deficit: When government expenditure is greater than its revenue over a specific period.

Budget Surplus: When government revenue exceeds its expenditure over a specific period.

Cyclical Budget Deficits and Surpluses

Cyclical deficits and surpluses are linked to fluctuations in the economic cycle. They are temporary changes in the fiscal position that depend on the stage of the business cycle.

During recessions, tax revenues fall (due to lower incomes and profits), while welfare spending rises (e.g., unemployment benefits). This tends to create a cyclical budget deficit.

During booms, tax revenues increase, and welfare spending falls, leading to a cyclical budget surplus.

Cyclical Deficit: A temporary shortfall in government revenue relative to spending, arising from downturns in the economic cycle.

Because cyclical deficits are linked to the business cycle, they may reverse automatically as economic growth returns.

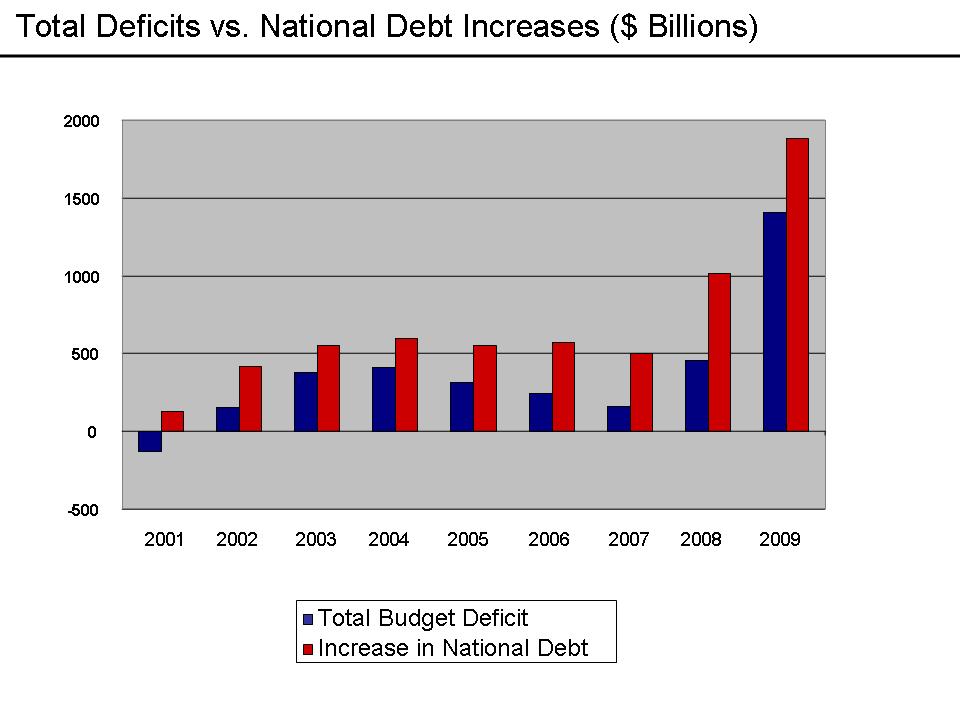

This graph illustrates the relationship between real GDP and budget balances, highlighting the cyclical deficit during economic downturns and the structural deficit that persists regardless of the economic cycle. Source

They are not necessarily evidence of poor fiscal management but rather a natural result of automatic stabilisers.

Structural Budget Deficits and Surpluses

Structural deficits and surpluses are independent of the economic cycle. They occur when government spending consistently exceeds revenue even at the trend rate of growth.

A structural deficit indicates that tax revenues are insufficient to cover government spending, even when the economy is at full employment.

A structural surplus means revenues are consistently higher than spending, regardless of cyclical changes.

Structural Deficit: A persistent shortfall in revenue compared to expenditure, existing even when the economy is operating at full capacity.

Structural imbalances reflect long-term policy decisions and require deliberate fiscal adjustments, such as changes to taxation or spending patterns.

Key Distinctions Between Cyclical and Structural Deficits

Understanding the difference between cyclical and structural imbalances is crucial for fiscal policy analysis:

Cause

Cyclical: Arises from changes in economic activity.

Structural: Arises from underlying fiscal policy choices.

Duration

Cyclical: Temporary and self-correcting with the cycle.

Structural: Persistent and requires deliberate government action.

Policy Implications

Cyclical: May not need intervention if automatic stabilisers correct the imbalance.

Structural: Demands active reform in taxation or spending.

The Role of Automatic Stabilisers

Automatic stabilisers are mechanisms in the fiscal system that naturally smooth fluctuations in aggregate demand. They influence cyclical deficits and surpluses.

Examples include:

Progressive taxation: Higher incomes generate proportionally higher tax revenues in a boom, while revenues fall sharply in a recession.

Welfare benefits: Payments rise automatically during unemployment, increasing government spending in downturns.

Automatic stabilisers mean the government’s fiscal position will fluctuate without policy changes, explaining why cyclical deficits or surpluses occur.

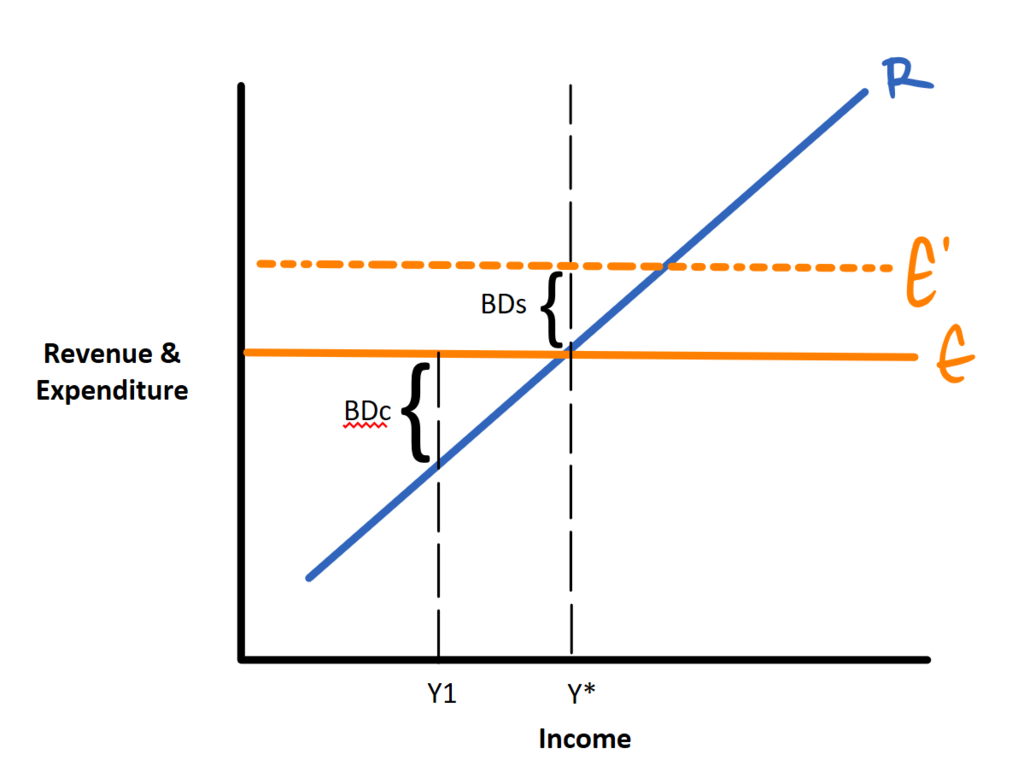

This diagram shows the cyclical nature of budget deficits and surpluses, emphasizing how they correspond with the phases of the economic cycle. Source

Measuring Cyclical vs Structural Deficits

Economists often attempt to separate the two types of deficits by estimating what the budget balance would be if the economy were operating at full capacity. This requires calculating a cyclically adjusted budget balance.

Cyclically Adjusted Budget Balance: An estimate of the government’s budget balance adjusted to reflect what it would be if the economy were at its potential output.

This measure allows policymakers to identify whether a deficit is structural (requiring action) or cyclical (likely to self-correct).

Policy Implications of Cyclical and Structural Deficits

Distinguishing between cyclical and structural deficits is important for fiscal policy decisions:

A cyclical deficit may be tolerated during recessions, as it reflects automatic stabilisers supporting demand.

A structural deficit requires corrective measures, such as tax rises or spending cuts, to restore fiscal sustainability.

Confusing the two could lead to inappropriate policy responses, e.g., tightening fiscal policy during a recession could worsen unemployment and reduce growth.

Consequences for Macroeconomic Performance

Both cyclical and structural imbalances have consequences for the economy, though their effects differ in significance and duration.

Cyclical Consequences

Short-term borrowing needs increase.

Debt rises temporarily but may fall as the cycle recovers.

Supports demand during recessions, preventing deeper downturns.

Structural Consequences

Persistent government borrowing increases long-term debt.

May lead to higher interest payments on debt.

Could reduce confidence in government finances, raising borrowing costs.

Requires fundamental policy reform to resolve.

Surpluses: Cyclical vs Structural

The same logic applies to surpluses:

A cyclical surplus may occur during a boom due to high revenues and lower welfare spending.

A structural surplus reflects consistently prudent fiscal management, though excessively high surpluses may indicate underinvestment in public services.

Linking to the AQA Specification

Students are expected to explain and evaluate the differences between cyclical and structural budget deficits and surpluses, and to understand their implications for fiscal sustainability and macroeconomic stability.

FAQ

Estimating a structural deficit requires knowing what the government’s fiscal balance would be if the economy were at full capacity. This involves forecasting potential GDP, which is uncertain.

Unexpected changes in productivity, labour force participation, or investment can make estimates inaccurate. Economists often disagree on the true level of trend growth, leading to different structural deficit figures.

Cyclical deficits usually increase borrowing in the short term, but lenders often see them as temporary.

If markets expect the deficit to shrink as the economy recovers, borrowing costs remain stable. However, prolonged downturns can blur the line between cyclical and structural, causing lenders to demand higher interest rates.

A government may accept a structural deficit if it prioritises long-term investment in infrastructure, healthcare, or education.

These expenditures can stimulate productivity growth, raising future tax revenues. Some governments also use structural deficits to avoid politically difficult spending cuts or tax rises.

Yes. In a boom, cyclical surpluses may encourage governments to increase spending or cut taxes.

If this stimulates demand too much, it can lead to inflationary pressures. Cyclical surpluses may also create political pressure for unsustainable permanent tax cuts or commitments to higher public spending.

Organisations like the IMF and OECD produce estimates of structural balances for different countries.

These assessments guide international comparisons, influencing credit ratings and investor confidence.

They also pressure governments to undertake reforms if structural deficits appear unsustainable, even when cyclical factors dominate in the short term.

Practice Questions

Define the difference between a cyclical budget deficit and a structural budget deficit. (2 marks)

1 mark for identifying that a cyclical budget deficit arises due to fluctuations in the economic cycle (e.g., during a recession tax revenues fall and welfare spending rises).

1 mark for identifying that a structural budget deficit exists even when the economy is at full capacity, caused by underlying fiscal imbalances.

Explain how cyclical and structural budget deficits can have different implications for government fiscal policy. (6 marks)

1–2 marks: Basic explanation of a cyclical deficit as temporary, linked to the business cycle, and often corrected by automatic stabilisers.

1–2 marks: Basic explanation of a structural deficit as persistent, existing even at trend growth, and requiring deliberate fiscal measures to resolve.

1 mark: Clear identification of policy implications for cyclical deficits (e.g., may not require immediate action, tolerated in recessions).

1 mark: Clear identification of policy implications for structural deficits (e.g., requires long-term reforms such as tax increases or spending cuts to ensure sustainability).

For full marks, the answer should contrast cyclical (short-term, automatic) with structural (long-term, policy-driven) and show awareness of differing fiscal responses.