AQA Specification focus:

‘The consequences of budget deficits and surpluses for macroeconomic performance.’

Fiscal deficits and surpluses shape economic performance by influencing growth, employment, inflation, debt sustainability, and confidence, with varying impacts in short- and long-term contexts.

Understanding Budget Deficits and Surpluses

A budget deficit occurs when government spending exceeds revenue in a given year. Conversely, a budget surplus arises when government revenue exceeds spending. These fiscal positions directly affect aggregate demand, long-term debt dynamics, and investor confidence.

Budget Deficit: The shortfall when government expenditure is greater than government revenue within a fiscal year.

Budget Surplus: The excess when government revenue is greater than government expenditure within a fiscal year.

Although these terms seem straightforward, their consequences for macroeconomic performance are multi-layered.

Short-Run Consequences of Budget Deficits

Expansionary Effects on Aggregate Demand

Deficits often stimulate the economy in the short term by raising aggregate demand (AD) through higher government spending or lower taxation. This can:

Increase economic growth if the economy is below potential output.

Reduce unemployment through higher demand for goods and services.

Support public services and welfare provision.

However, expansionary deficits may also generate demand-pull inflation if the economy is close to full capacity.

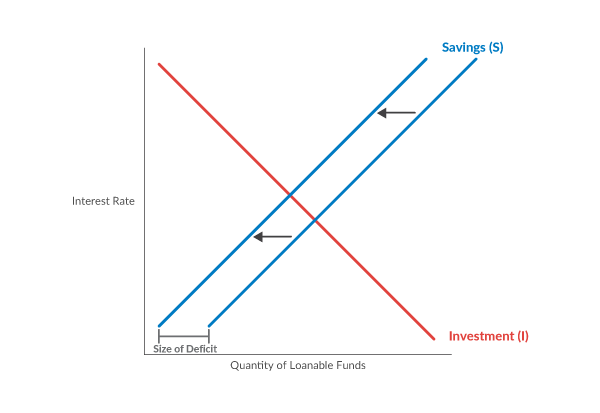

Borrowing and Interest Rates

Deficits usually require financing through government borrowing. Increased borrowing may:

Push up interest rates if demand for loanable funds rises, potentially crowding out private investment.

Lead to higher debt servicing costs, diverting funds from productive expenditure.

This diagram shows how an increase in government borrowing (deficit) can lead to higher interest rates, which may crowd out private investment, thereby affecting economic growth. Source

Long-Run Consequences of Budget Deficits

National Debt Accumulation

Persistent deficits add to the national debt, defined as the total stock of outstanding government borrowing. A rising debt-to-GDP ratio can create concerns about long-term fiscal sustainability.

National Debt: The total outstanding amount the government owes, accumulated over successive years of deficits.

Confidence and Stability

Large deficits may erode investor confidence, leading to:

Higher yields demanded on government bonds.

Pressure on the currency through reduced foreign investor appetite.

Greater vulnerability to external shocks.

Intergenerational Equity

Future taxpayers may bear the burden of servicing today’s debt, raising concerns about equity between generations.

Consequences of Budget Surpluses

Stabilising National Debt

Running a surplus allows governments to:

Repay existing debt.

Reduce debt interest payments.

Improve fiscal credibility with investors.

This can strengthen macroeconomic stability and confidence.

Contractionary Effects

However, persistent surpluses may:

Reduce aggregate demand, slowing economic growth.

Risk higher unemployment if spending cuts or tax rises dampen consumption and investment.

Undermine public service provision if expenditure is reduced excessively.

Cyclical Considerations

Automatic Stabilisers

Deficits and surpluses often reflect the state of the economic cycle:

During recessions, tax revenues fall while welfare spending rises, creating cyclical deficits.

During booms, rising tax receipts and lower welfare spending generate surpluses.

These stabilisers smooth fluctuations in aggregate demand and help maintain stability without deliberate policy changes.

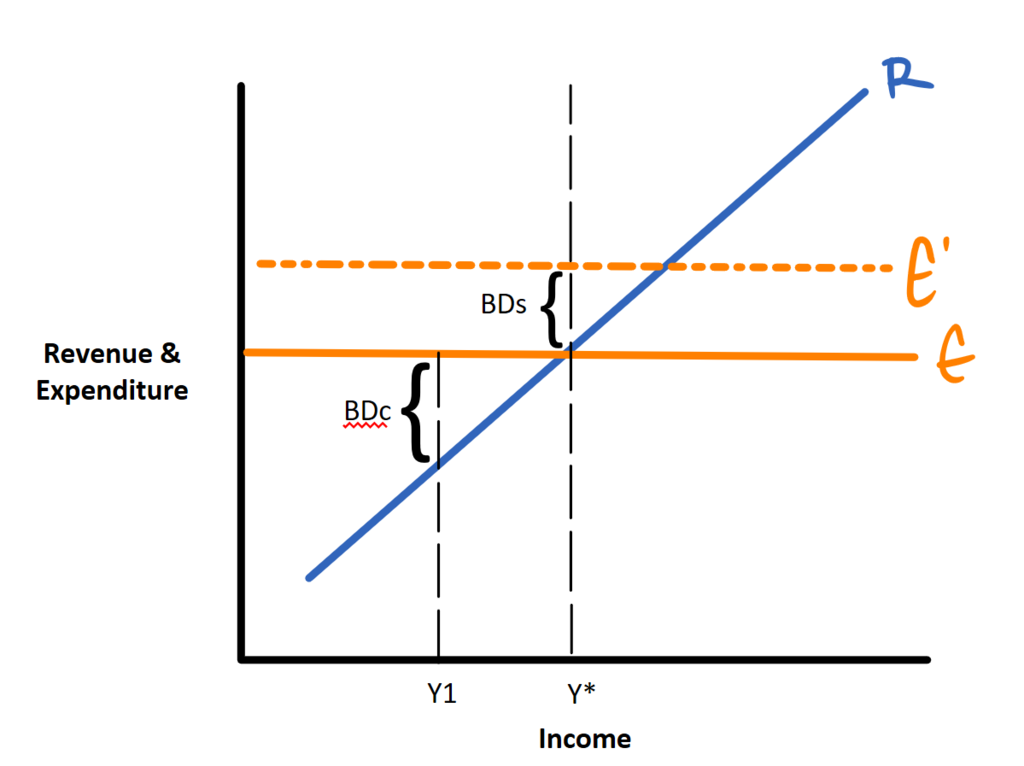

Structural Considerations

Structural Deficits

Some deficits persist even when the economy is at full employment. These structural deficits reflect imbalances such as overspending or insufficient revenue-raising capacity.

This diagram differentiates between cyclical and structural budget deficits, highlighting how economic fluctuations and underlying fiscal imbalances contribute to government borrowing. Source

They suggest deeper fiscal problems requiring reform rather than short-term stimulus.

Long-term reliance on borrowing may undermine economic growth potential.

Inflationary and External Balance Consequences

Deficits and surpluses also influence broader macroeconomic variables:

Inflation: Deficits risk fuelling demand-pull inflation, while surpluses may dampen inflationary pressures.

Balance of Payments: Deficits can increase imports by stimulating domestic demand, worsening the current account. Surpluses may moderate import demand, supporting external balance.

Evaluating the Consequences

Potential Benefits of Deficits

Stimulate demand and growth in recession.

Support employment and welfare provision.

Finance long-term investments in infrastructure and education, raising potential output.

Potential Costs of Deficits

Rising debt servicing burden.

Higher inflationary pressures.

Crowding out of private investment.

Loss of fiscal credibility.

Potential Benefits of Surpluses

Reduce debt and interest payments.

Enhance investor confidence.

Provide fiscal space for future crises.

Potential Costs of Surpluses

Contractionary effects on growth and employment.

Possible neglect of infrastructure and social investment.

Political unpopularity due to higher taxes or spending cuts.

Balancing Fiscal Outcomes

The consequences of deficits and surpluses depend heavily on context:

Economic cycle position (recession vs boom).

Size and persistence of fiscal imbalance.

Use of funds (investment vs consumption).

Debt-to-GDP ratio and investor perceptions.

Ultimately, deficits can be beneficial in downturns, while surpluses may strengthen long-term sustainability, but excessive reliance on either risks damaging macroeconomic performance.

FAQ

In the short term, a deficit can stimulate demand and reduce unemployment, especially during a recession. This may support growth but risk inflation if capacity is tight.

In the long term, persistent deficits increase national debt, raise debt servicing costs, and may erode investor confidence. This reduces fiscal flexibility for future crises.

A surplus might reduce aggregate demand if spending cuts or tax rises lower consumption and investment. This risks slower growth and higher unemployment.

Public services may also be underfunded, leading to lower investment in areas like health, education, and infrastructure, which can weaken long-term productivity.

Developed economies often borrow in their own currency, reducing default risk. They may sustain higher debt levels without losing market confidence.

Developing economies face higher borrowing costs and potential capital flight, making deficits more destabilising.

Exchange rate vulnerability in developing nations can also amplify the inflationary effects of deficits.

Investor confidence influences borrowing costs. If markets trust fiscal policy, governments can run moderate deficits without sharp increases in interest rates.

If confidence falls, even small deficits can trigger rising bond yields, currency depreciation, and reduced foreign investment.

Yes. Running a surplus reduces existing debt and lowers interest costs, creating fiscal space.

When a downturn occurs, governments with healthier finances can afford larger deficits to stimulate demand without risking investor panic or unsustainable debt levels.

Practice Questions

Define a budget surplus and explain one possible macroeconomic consequence of running a persistent budget surplus. (2 marks)

1 mark for definition: budget surplus = when government revenue exceeds government spending.

1 mark for identifying a valid macroeconomic consequence (e.g. reduced aggregate demand, higher unemployment, reduced growth, debt reduction).

Discuss the possible macroeconomic consequences of a government running a large budget deficit. (6 marks)

Up to 2 marks for clear explanation of a budget deficit (spending exceeds revenue, financed by borrowing).

Up to 2 marks for development of consequences such as:

Higher debt servicing costs (interest payments).

Potential crowding out of private investment due to higher interest rates.

Risk of inflationary pressures if economy is near full capacity.

Worsening of balance of payments through increased import demand.

Up to 2 marks for evaluative points, such as:

Deficits can be beneficial during a recession by stimulating demand.

Impact depends on debt-to-GDP ratio and long-term sustainability.

Scale and persistence of deficit matter for overall macroeconomic effects.