AQA Specification focus:

‘How fiscal policy can be used to influence aggregate supply.’

Fiscal policy can shape not only demand but also long-run economic capacity. By targeting aggregate supply (AS), governments aim to improve productivity, efficiency, and sustainable growth.

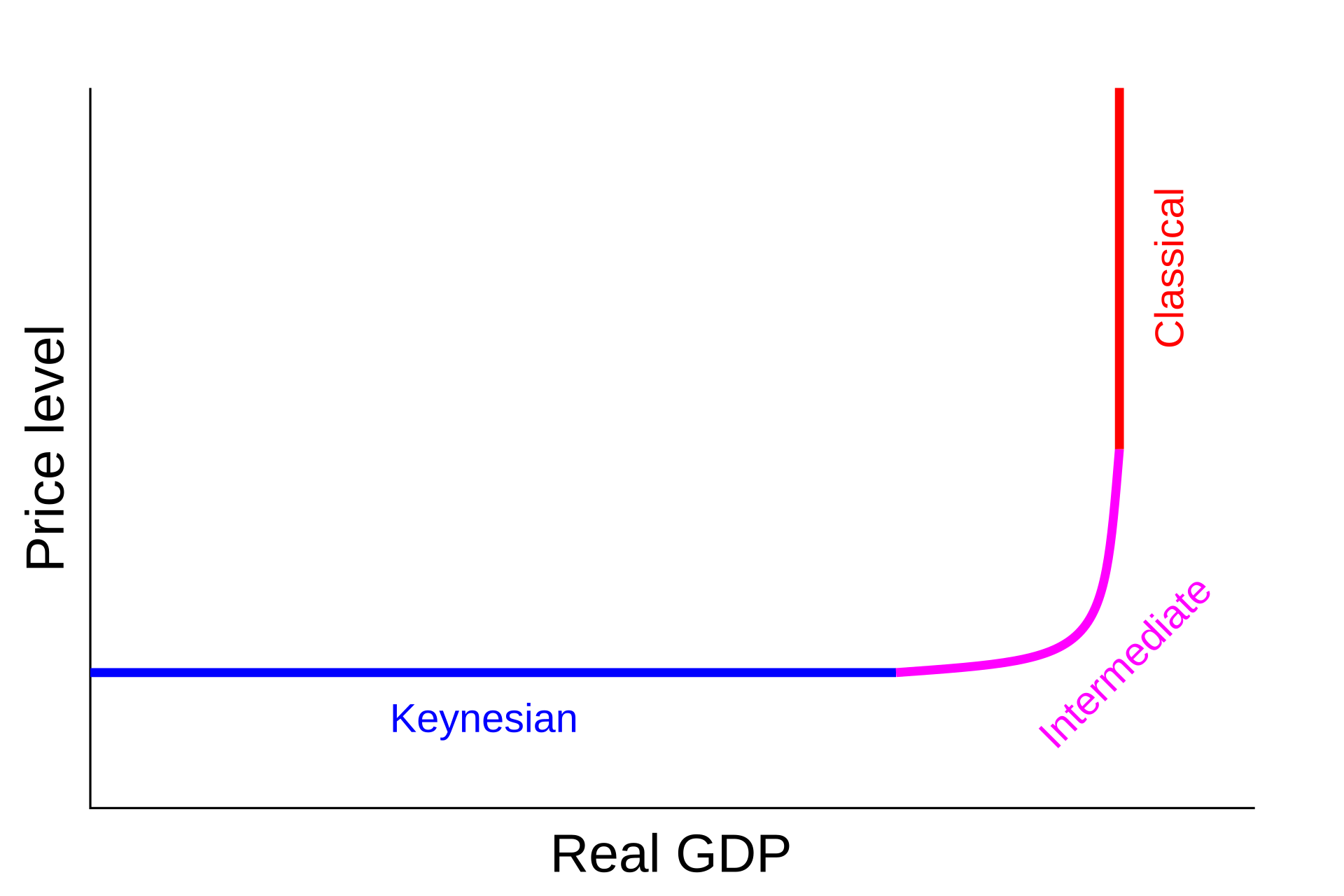

The Aggregate Supply curve demonstrates the total output an economy can produce at various price levels, highlighting the potential impact of fiscal policy on long-run economic capacity. Source

Understanding Fiscal Policy and Aggregate Supply

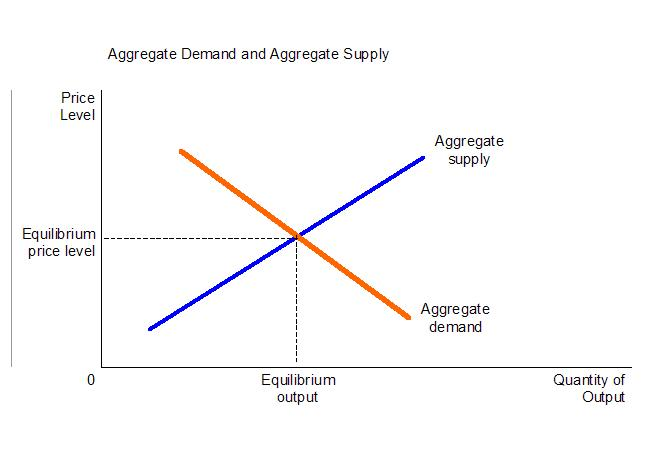

Fiscal policy refers to government decisions on taxation, spending, and borrowing. While often linked with managing aggregate demand (AD), fiscal policy can also be directed at boosting aggregate supply (AS), which represents the total productive capacity of an economy at different price levels.

Aggregate Supply (AS): The total quantity of goods and services that firms in an economy are willing and able to produce at various price levels.

Policies influencing AS generally focus on the long-run aggregate supply (LRAS) by improving efficiency, reducing structural barriers, and encouraging investment.

Government Spending and Supply-Side Capacity

Government expenditure can directly enhance productive potential:

Infrastructure investment: Roads, railways, and energy grids reduce business costs and improve efficiency.

Education and training: Improves human capital, raising productivity and adaptability of the workforce.

Research and development subsidies: Encourage innovation and technological progress.

Healthcare spending: A healthier workforce is more productive and reliable.

By targeting such areas, fiscal policy can shift LRAS outward, leading to higher potential output and improved long-term growth prospects.

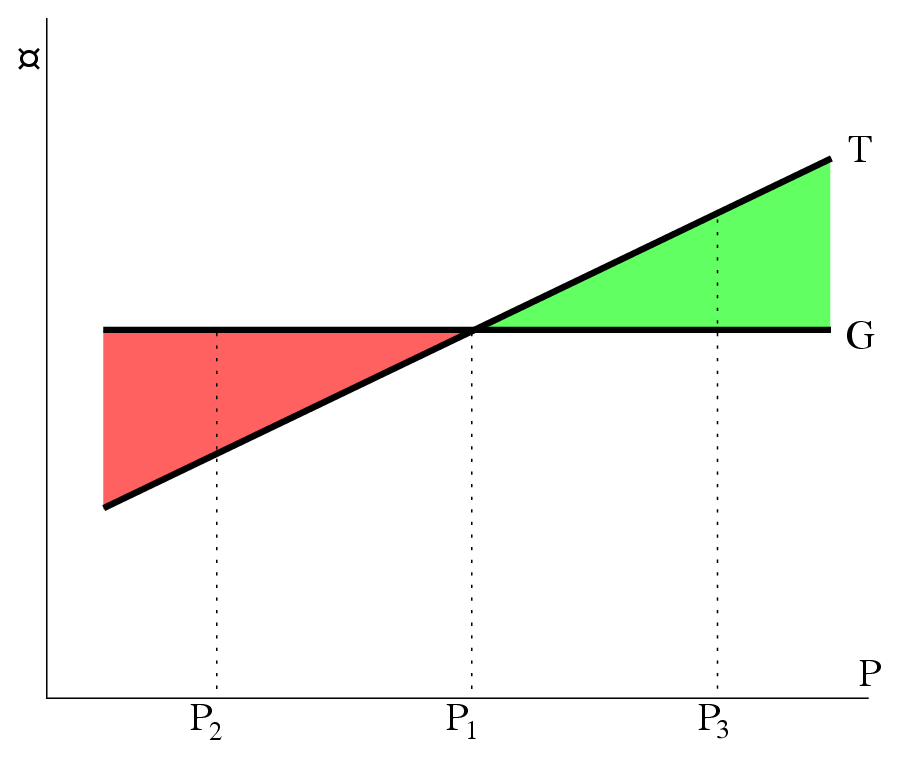

Taxation and Incentives

Taxation influences both household and business behaviour. When structured appropriately, it can provide powerful supply-side incentives.

Lower corporation tax: Increases retained profits, encouraging firms to invest in capital and innovation.

Lower income tax rates: May increase labour supply by improving incentives to work and reducing the tax wedge.

Investment allowances and tax reliefs: Support entrepreneurship and capital formation.

Reduced indirect taxes: May lower production costs, improving international competitiveness.

Tax Wedge: The difference between what employers pay for labour and what workers actually take home after tax.

Tax reforms that reduce distortions can encourage efficiency and participation in both labour and capital markets.

The Fiscal Policy diagram illustrates the relationship between government spending, taxation, and economic output, emphasizing the role of fiscal policy in influencing aggregate supply. Source

Fiscal Policy and Long-Run Economic Growth

When fiscal policy is designed to influence AS, its ultimate goal is to raise the trend rate of growth.

Trend Rate of Growth: The long-term average rate at which an economy can grow without generating inflationary pressure, reflecting improvements in productive capacity.

Policies supporting innovation, skills development, and enterprise ensure the economy grows sustainably, rather than relying solely on demand-side stimulus.

The Keynesian Aggregate Supply curve illustrates how fiscal policy can stimulate economic output without leading to inflation, especially when there is underutilized capacity in the economy. Source

Fiscal Policy’s Role in Reducing Bottlenecks

Fiscal measures can address supply-side constraints that hinder output:

Transport investment reduces congestion, improving logistics.

Housing initiatives can ease labour mobility by making relocation affordable.

Regional development spending balances growth by reducing disparities and preventing overheating in certain areas.

Such measures help reduce structural inefficiencies, allowing the economy to function closer to full capacity.

Distinguishing Fiscal Policy from Supply-Side Policy

It is important to distinguish fiscal policy aimed at AS from general supply-side policy. Fiscal policy uses government spending and taxation to target supply, whereas supply-side policy can include a wider range of free-market or interventionist measures.

Examples:

Fiscal: Increased government spending on R&D grants.

Broader supply-side: Deregulation to reduce business constraints (not necessarily fiscal).

Fiscal Policy and Productivity

Fiscal choices can directly raise labour productivity and capital productivity:

Human capital investment raises output per worker.

Infrastructure reduces wasted time and resources.

Tax incentives encourage technological upgrades.

These improvements shift the productive potential of the economy, not just short-term demand.

Potential Limitations of Using Fiscal Policy to Influence AS

While fiscal policy has a clear role in influencing AS, limitations exist:

Time lags: Infrastructure and education take years to yield results.

Opportunity cost: Spending on AS improvements may mean higher taxation or cuts elsewhere.

Crowding out: Increased government borrowing to finance spending might reduce private sector investment.

Political constraints: Short-term political goals may undermine consistent long-term investment strategies.

Despite these limitations, fiscal policy remains a crucial tool for shaping long-run supply capacity.

Key Channels Through Which Fiscal Policy Influences AS

To summarise the main mechanisms, fiscal policy influences AS via:

Public investment → improved infrastructure and capacity.

Education and training → enhanced labour productivity.

Taxation reforms → incentives for work and investment.

Healthcare → healthier, more reliable workforce.

Targeted subsidies → innovation and competitiveness.

Each of these channels contributes to shifting the long-run aggregate supply curve outward, supporting sustainable economic growth.

FAQ

Fiscal policy targeting aggregate supply focuses on long-run productive capacity rather than short-term fluctuations in demand.

While demand-side fiscal policy might involve temporary tax cuts to boost consumption, supply-side fiscal policy uses spending and taxation to improve efficiency, productivity, and investment.

Examples include infrastructure investment, education funding, and corporate tax incentives that raise the economy’s potential output rather than just increasing spending power.

Infrastructure reduces costs and inefficiencies that limit business activity. Better transport systems cut delivery times and congestion, while reliable energy networks support continuous production.

It also improves connectivity between regions, enabling labour mobility and reducing bottlenecks in the economy.

By lowering barriers to efficient production, infrastructure spending has a multiplier effect, improving productivity across multiple sectors simultaneously.

Taxation affects the incentive to work and the effective reward for labour.

Lower income tax increases disposable income and encourages participation in the labour market.

Reductions in marginal tax rates may increase willingness to work overtime or accept promotion.

Reforms that reduce the tax wedge encourage both employers and workers to engage more fully in the labour market.

These changes increase labour supply and can raise the economy’s productive capacity.

Education enhances human capital, making workers more skilled, adaptable, and productive.

Improved training raises efficiency and innovation, while reducing structural unemployment. Unlike demand-focused spending, education investment has long-term benefits by raising the sustainable level of output, shifting the LRAS curve outward.

This ensures economic growth is supported without relying on continuous short-term demand stimuli.

Risks include:

Time lags: Education or infrastructure projects take years before productivity benefits are realised.

Fiscal pressures: Funding these policies may increase borrowing or require higher taxation elsewhere.

Uncertainty of outcomes: Investments may not deliver expected improvements in productivity.

Political cycles: Governments may prioritise short-term popularity over consistent long-term strategies.

These factors can limit the effectiveness of fiscal policy in sustainably shifting aggregate supply.

Practice Questions

Define aggregate supply and explain how fiscal policy can influence it in the long run. (2 marks)

1 mark for definition of aggregate supply: the total quantity of goods and services firms are willing and able to produce at various price levels.

1 mark for explanation of how fiscal policy can influence it in the long run, e.g., government spending on education or infrastructure raises productive capacity.

Discuss how changes in taxation could influence the UK’s long-run aggregate supply. (6 marks)

1–2 marks: Basic identification of taxation changes (e.g., lowering corporation tax, reducing income tax).

1–2 marks: Explanation of how these affect incentives (e.g., encourage investment, increase labour supply).

1–2 marks: Development of the argument in the context of long-run aggregate supply (e.g., increased productivity, higher potential output, improved efficiency).

Award full marks for a well-developed discussion with clear links to LRAS rather than short-term aggregate demand.