AQA Specification focus:

‘They should be able to assess the impact of measures used to rebalance the budget.’

Introduction

Governments often face budget deficits or surpluses, requiring strategic measures to restore balance. Rebalancing the budget can involve changes in taxation, spending, or broader structural reforms.

Understanding Budget Rebalancing

What Is Budget Rebalancing?

Budget rebalancing refers to policies aimed at reducing a deficit (where government spending exceeds revenue) or adjusting a surplus (where revenues exceed spending) to achieve sustainable fiscal outcomes.

Budget Balance: The difference between government revenue (mainly from taxation) and government expenditure over a specific period.

A persistent deficit can lead to a rise in the national debt, while a surplus may create space for tax cuts or future spending. The choice of rebalancing measures depends on government priorities, economic conditions, and political constraints.

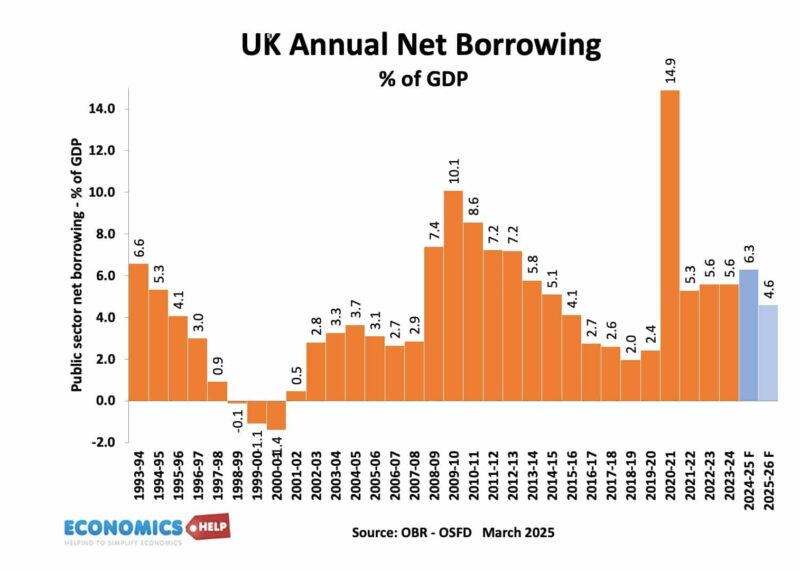

This chart shows the UK's annual net borrowing as a percentage of GDP from 1997 to 2022, indicating periods of deficit and surplus. Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a significant increase in borrowing. Source

Types of Measures Used to Rebalance the Budget

1. Expenditure-Based Measures

Governments can attempt to reduce the deficit by cutting public spending. These measures may target both current expenditure (such as welfare payments) and capital expenditure (infrastructure investment).

Cutting welfare spending: Reducing benefits or tightening eligibility criteria.

Reducing public sector pay: Limiting wage growth or freezing salaries.

Delaying capital projects: Postponing or cancelling infrastructure investments.

These policies often reduce the size of government intervention in the economy, but may negatively affect aggregate demand (AD) and long-term growth prospects.

2. Revenue-Based Measures

Another strategy is to increase government revenue through changes in taxation.

Raising direct taxes (e.g. income tax, corporation tax).

Increasing indirect taxes (e.g. VAT, excise duties).

Reducing tax evasion and avoidance through stricter enforcement.

Revenue measures may improve the fiscal position quickly but can reduce incentives to work, save, and invest.

3. Structural Reforms

Structural measures focus on long-term fiscal sustainability, addressing the underlying causes of imbalances.

Pension reform: Increasing retirement ages or altering contributions to reduce future liabilities.

Healthcare reform: Improving efficiency and cost-effectiveness in healthcare provision.

Public sector efficiency drives: Streamlining bureaucracy and improving productivity.

These measures often take time to yield results but are important for reducing structural deficits.

Distinguishing Between Deficit Types

It is crucial to understand whether the imbalance is cyclical or structural:

Cyclical Deficit: A budget deficit caused by temporary downturns in the economic cycle, such as recessions reducing tax revenue and increasing welfare spending.

Structural Deficit: A budget deficit that exists even when the economy is operating at full capacity, caused by a fundamental mismatch between spending commitments and tax revenue.

Cyclical issues may correct themselves with recovery, whereas structural imbalances require deeper fiscal reforms.

Impacts of Budget Rebalancing

Macroeconomic Impacts

On growth: Spending cuts can reduce AD, lowering short-term growth, while well-designed tax reforms may enhance long-term aggregate supply (AS).

On unemployment: Reduced spending can lead to job losses in the public sector and weaker demand in the private sector.

On inflation: Indirect tax rises can increase the price level, while reduced demand may suppress inflationary pressures.

On debt sustainability: Successful rebalancing can improve investor confidence, reduce borrowing costs, and stabilise debt-to-GDP ratios.

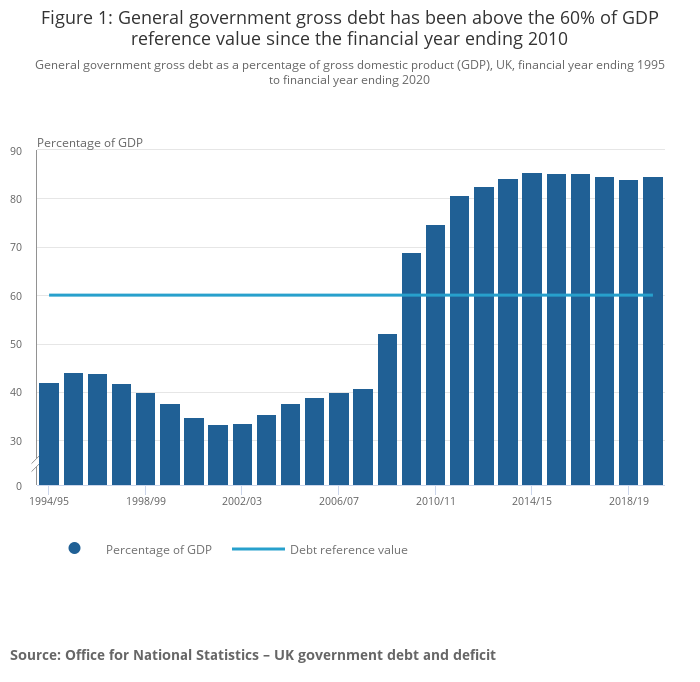

This figure depicts the UK's general government gross debt as a percentage of GDP, highlighting trends and the impact of fiscal policies on national debt levels. The data reflects the UK's fiscal position up to the financial year ending 2020. Source

Microeconomic Impacts

Distributional effects: Spending cuts and tax rises may disproportionately affect lower-income households.

Incentives: Higher direct taxes can reduce incentives to work, while cuts to welfare benefits may increase incentives to seek employment.

Resource allocation: Reduced public investment can shift resources away from government-led projects towards private sector activity.

Common UK Measures to Rebalance the Budget

In the UK, governments have historically employed a mix of measures:

Austerity policies (post-2010): Significant reductions in welfare spending and departmental budgets.

Tax changes: Adjustments to VAT, corporation tax, and income tax thresholds.

Public service reforms: Efforts to improve efficiency in health, education, and local government.

Such measures illustrate the balance between short-term fiscal necessity and long-term economic consequences.

Evaluating the Effectiveness of Measures

When assessing rebalancing strategies, several factors must be considered:

Economic Conditions

In a recession, spending cuts may worsen unemployment and hinder recovery.

In periods of strong growth, tax increases may be less damaging.

Credibility and Confidence

Markets often reward credible plans to reduce deficits with lower interest rates on government debt.

Overly harsh measures, however, risk undermining political stability.

Flexibility

Some measures, such as tax adjustments, can be implemented quickly.

Structural reforms, by contrast, require long-term planning and gradual implementation.

Equity Considerations

Rebalancing policies must consider fairness. For example, progressive tax rises may be more acceptable than regressive ones.

Equations for Fiscal Balance

Budget Balance (BB) = Government Revenue (GR) – Government Expenditure (GE)

GR = Total taxation and other receipts (£ billions)

GE = Total current and capital spending (£ billions)

A negative balance represents a deficit, while a positive balance represents a surplus.

Long-Term Implications of Rebalancing

While rebalancing is often necessary to ensure fiscal sustainability, the chosen mix of policies has wide-ranging consequences. Governments must weigh:

Short-term pain versus long-term stability.

Equity versus efficiency.

Political feasibility versus economic necessity.

Effective rebalancing supports sustainable growth and financial stability, but inappropriate timing or poor design can deepen economic problems rather than resolve them.

FAQ

Governments sometimes prefer spending cuts because they can directly reduce the size of the public sector and avoid discouraging private sector activity.

Tax rises may reduce incentives to work, save, and invest, potentially harming long-term economic growth. Spending cuts, though politically difficult, may be seen as more sustainable if they reduce structural deficits rather than temporarily boosting revenue.

The timing is crucial. Implementing austerity during a recession may worsen unemployment and slow recovery.

In contrast, rebalancing during periods of strong economic growth can reduce the risk of overheating and be less damaging to demand. The same measure, therefore, can have very different outcomes depending on the stage of the economic cycle.

Public and market confidence determines how effective measures will be.

If households and firms believe fiscal reforms are credible, they may adjust behaviour positively, e.g., higher investment confidence.

If measures appear unstable or unfair, they may trigger opposition, reduce compliance with tax, and undermine economic stability.

Structural reforms, such as pension or healthcare adjustments, aim at long-term sustainability rather than immediate savings.

Unlike tax increases or benefit cuts, which impact revenue and expenditure quickly, structural reforms often involve gradual phasing, political negotiation, and delayed fiscal effects. They address underlying drivers of deficits rather than short-term imbalances.

Bodies such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) often provide guidance or conditions for financial support.

This can include:

Requiring deficit reduction targets.

Recommending specific reforms like privatisation or tax restructuring.

Monitoring progress to ensure credibility with investors.

Such influence can shape the scale, timing, and form of domestic rebalancing policies.

Practice Questions

Define the term budget deficit and explain how it differs from a budget surplus. (3 marks)

1 mark for correctly defining budget deficit: when government expenditure exceeds government revenue in a given period.

1 mark for correctly defining budget surplus: when government revenue exceeds government expenditure in a given period.

1 mark for explaining the difference clearly: deficit implies borrowing/raising debt, surplus implies savings/reduced borrowing.

Discuss two measures a government might use to rebalance the budget and explain one possible consequence of each measure. (6 marks)

Up to 2 marks for identifying and explaining the first measure (e.g., increasing taxes, reducing public spending, structural reforms).

Up to 1 mark for explaining a possible consequence of the first measure (e.g., reduced consumer demand, higher unemployment, improved fiscal position).

Up to 2 marks for identifying and explaining the second measure.

Up to 1 mark for explaining a possible consequence of the second measure.

Maximum 6 marks: responses must show clear knowledge and application. Evaluation (e.g., fairness, impact depending on economic conditions) not required but can strengthen explanation.