AQA Specification focus:

‘The significance of the size of the national debt.’

The question of how big national debt should be is central to fiscal policy debates, influencing economic stability, government credibility, and long-term growth prospects.

Understanding National Debt

Definition of National Debt

National Debt: The total amount of money a government owes to creditors, accumulated through past budget deficits when expenditure exceeds revenue.

The size of the national debt reflects both the borrowing needs of the government and the sustainability of its fiscal position. Unlike private debt, national debt can be sustained over long periods, but its implications depend on context.

Debt vs Budget Deficit

A budget deficit occurs when annual government spending exceeds revenue in a given fiscal year. The national debt is the accumulation of all past deficits minus any surpluses.

Measuring the Significance of National Debt

Debt-to-GDP Ratio

The size of national debt is often expressed as a debt-to-GDP ratio. This compares the nominal value of debt with the country’s total annual economic output.

Debt-to-GDP Ratio (%) = (National Debt ÷ Gross Domestic Product) × 100

National Debt = Total outstanding government liabilities (£)

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) = Value of all goods and services produced in an economy annually (£)

A higher ratio suggests greater debt relative to the economy’s productive capacity.

Nominal vs Real Burden

Nominal debt is the actual monetary value owed.

Real debt burden adjusts for inflation and interest rates, determining the affordability of repayments over time.

Factors Influencing How Big Debt Should Be

Economic Growth

If GDP grows faster than debt, the debt-to-GDP ratio falls, making higher debt more sustainable. Conversely, weak growth increases the relative burden.

Interest Rates

Low interest rates reduce the cost of servicing debt, enabling governments to manage larger levels sustainably. Rising interest rates increase debt repayment costs, crowding out other spending.

Market Confidence

Investor confidence determines how easily governments can borrow. If confidence falls, borrowing costs rise, and concerns of fiscal unsustainability emerge.

Inflation

Moderate inflation can reduce the real value of debt, easing repayment. However, high inflation risks destabilising markets and eroding savings.

Benefits of a Larger National Debt

Stabilising demand during recessions by financing stimulus spending.

Spreading the cost of long-term investments (e.g., infrastructure, education).

Maintaining liquidity in financial markets by providing a safe asset (government bonds).

Intergenerational fairness by ensuring future beneficiaries share the cost of current investment.

Risks of Excessive National Debt

Higher debt servicing costs: More tax revenue diverted to interest payments.

Crowding out: Private sector borrowing may be displaced if government borrowing drives up interest rates.

Reduced fiscal flexibility: Less room to respond to economic shocks.

Loss of confidence: Financial markets may demand higher returns, worsening debt dynamics.

Intergenerational burden: Future taxpayers may face higher taxes to repay today’s borrowing.

Determining “How Big” Is Too Big

No Absolute Threshold

There is no universal maximum level of debt, as sustainability depends on economic context. Advanced economies with stable institutions may sustain higher levels than developing economies.

The UK Context

The UK’s national debt is financed largely in domestic currency, giving flexibility.

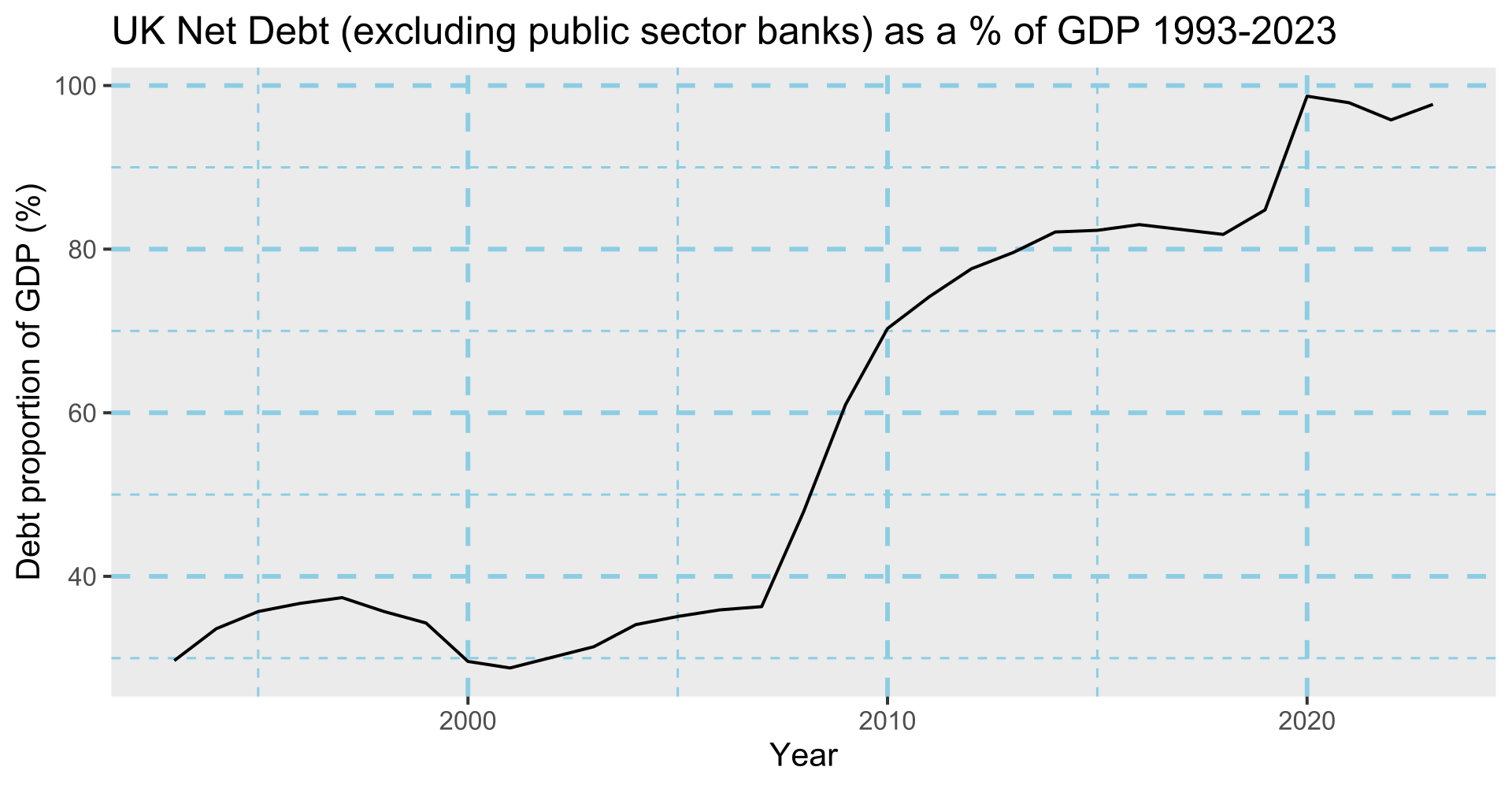

This chart shows the UK's national debt as a percentage of GDP from 1993 to 2023, highlighting periods of increase and the government’s fiscal responses. Source

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) monitors debt sustainability and forecasts long-term trends.

UK debt has historically risen sharply during wars or crises, followed by periods of gradual reduction relative to GDP.

International Comparisons

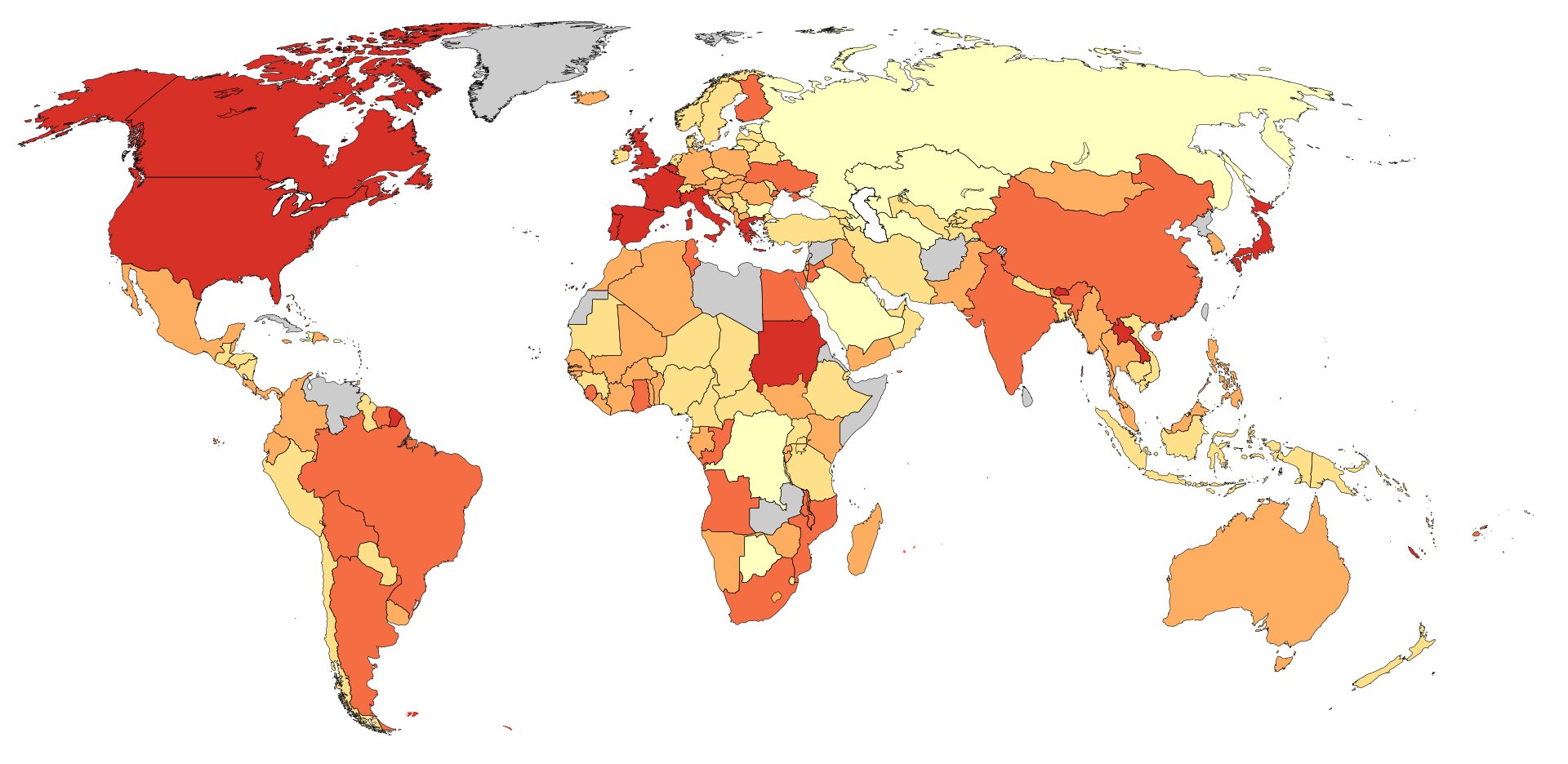

Countries like Japan sustain very high debt-to-GDP ratios with low interest rates, while others face crises at much lower levels. Context and policy credibility matter more than the number itself.

This map displays government debt as a percentage of GDP for various countries, offering a comparative view of fiscal positions worldwide. Source

Principles for Evaluating National Debt Size

Intergenerational Equity

Governments must weigh the fairness of passing debt onto future generations. If debt funds long-term productivity gains, it may be justified.

Fiscal Rules

Many governments adopt fiscal rules, such as keeping debt-to-GDP below a set threshold, to maintain discipline.

Structural vs Cyclical Considerations

Cyclical debt rises temporarily in downturns but falls in recovery.

Structural debt reflects persistent imbalances, which are more problematic.

Role of Policy Choices

Governments can raise taxes, cut spending, or borrow more to manage debt.

Supply-side policies that boost growth can reduce the debt ratio indirectly.

Key Takeaways for A-Level Students

The significance of debt size lies in its sustainability, not the absolute figure.

Debt-to-GDP ratio is the key measure.

Factors like growth, interest rates, inflation, and confidence shape how much debt is manageable.

Both benefits and risks exist, and governments must strike a balance between using debt for stabilisation and ensuring long-term sustainability.

FAQ

The absolute size of debt tells us little about affordability. Sustainability depends on whether a government can service debt without cutting essential spending or raising unsustainable taxes.

Debt relative to GDP provides context. For example, a large but growing economy can manage higher debt levels, whereas a smaller economy may struggle with the same absolute amount.

Debt is issued in two main forms: short-term and long-term.

Short-term debt must be refinanced quickly, creating rollover risks.

Long-term debt locks in interest rates, offering more stability.

If a country owes debt in its own currency, repayment is easier to manage. Debt owed in foreign currencies can be riskier, as exchange rate fluctuations increase vulnerability.

Investor confidence shapes borrowing costs. If markets believe debt is manageable, governments can borrow cheaply.

Loss of confidence, however, leads to higher yields on bonds, increasing servicing costs. In extreme cases, investors may refuse to lend, triggering a fiscal crisis.

Debt can finance long-term investment that boosts productivity, such as infrastructure, healthcare, and education. These projects can increase future GDP, lowering the debt-to-GDP ratio over time.

Debt-financed spending during recessions can also stabilise demand and prevent deeper downturns. In these cases, high debt supports economic resilience.

Post-WWII Britain: National debt exceeded 200% of GDP but was reduced gradually through growth and moderate inflation.

Eurozone crisis (2010s): Countries like Greece faced crises at lower debt levels because of weak growth and lack of monetary flexibility.

These examples show that context, growth prospects, and policy credibility are as important as the debt figures themselves.

Practice Questions

Define the term “national debt”. (2 marks)

1 mark for stating that national debt is the total amount owed by the government.

1 mark for specifying that it is the accumulation of past budget deficits minus any surpluses.

Explain why the significance of the size of national debt depends on the debt-to-GDP ratio rather than the absolute value of debt. (6 marks)

1 mark for recognising that the debt-to-GDP ratio compares debt to the economy’s output.

1 mark for explaining that a larger economy can sustain a bigger debt burden.

1 mark for noting that the ratio reflects the economy’s ability to service debt.

1 mark for linking sustainability to economic growth (e.g., faster GDP growth lowers the ratio).

1 mark for identifying that the same level of debt may be sustainable in one country but not in another, depending on GDP.

1 mark for clear, logical explanation that the ratio, not the absolute figure, shows the real economic significance.